Is the era of management over?

Trying to control people in a corporate environment can be counterproductive Image: REUTERS/Jason Reed

"The key to management is to get rid of the managers," advised Ricardo Semler, whose TED Talk went viral, introducing terms such as “industrial democracy” and “corporate re-engineering”. It’s important to point out that Mr. Semler isn’t an academic or an expert in management theory, he is the CEO of a successful industrial company. His views are unlikely to represent mainstream thinking on organizational design. But perhaps it is time we redefine the term “manager”, and question whether the idea of “management” as it was inherited from the industrial era, has outlived its usefulness.

The World Bank estimates the size of the global workforce at about 3.5 billion people, and by no means would I expect, much less advocate, that those who are employed today will transition into a management-free structure in the near or even medium term. The vast majority of work involving human labour is still best carried out in a traditional organisational structure.

In a world of VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity), it is the tech unicorns that will be the early adopters of a post-hierarchical model. In fact, some have already embraced it. Today’s competitive landscape is defined by one word: disruption. The ideas of incremental progress, continuous improvement, and process optimizations just don’t cut the mustard anymore; those practices are necessary, but insufficient. It is now impossible to build enduring success without “intrapreneurship” - creating new ideas from within an organisation.

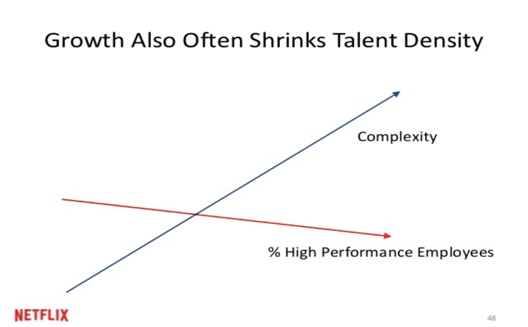

The organisational dilemmas faced by ambitious disruptors are best exemplified by Netflix. Their human resources guru, Patty McCord, identified a problem that appears obvious in retrospect: as businesses grow, so does their complexity. But that comes at a cost of shrinking talent density: the proportion of high-performers within an organistion.

The slide deck she developed with the CEO of Netflix, Reed Hastings, went viral, and Sheryl Sandberg referred to it as possibly the most important document to come out of Silicon Valley. That said, Patty McCord did not earn her accolades by identifying problems. What captivated everyone’s imagination were the unorthodox solutions that she offered: “Over the years we learned that if we asked people to rely on logic and common sense instead of on formal policies, most of the time we would get better results, and at lower cost.”

The commentary on Netflix’s corporate culture often focuses on its concrete HR policies, such as self-allotted vacations, and the absence of travel expense reports. But these are just derivatives of a larger vision: high business complexity need not be managed with standard processes and ever-growing rulebook. Patty McCord advocated the exact opposite: limit the tyranny of procedures, bring on board high-performers, and let them self-manage in an environment of maximum flexibility.

Today, we define management as the process of dealing with or controlling things or people. And if this is not a red flag to a CEO running anything other than a widget factory, I don’t know what is. Controlling things no longer appears plausible, and controlling people is downright counterproductive. Steve Jobs hit the nail on the head when he said: “It doesn’t make sense to hire smart people and then tell them what to do; we hire smart people so they can tell us what to do.”

Apple’s co-founder is rightfully considered one of the greatest visionaries of our time, but had he been born in, say, the 17th century – or even 50 years earlier than he was – I doubt such a pronouncement would have resonated with his contemporaries. The post-management era is only just beginning to dawn. And it is the ever-accelerating pace of technological progress that is responsible for destroying old paradigms.

Having smart people tell landowners what to do in a pre-industrial society would not have led to better economic outcomes. In the best-case scenario, it would have invited ridicule. There was no evidence to suggest, at the time, that the production and population growth were not one of the same.

While the division of labour was the hallmark of the industrial era, it is becoming increasingly difficult today to parse out and allocate white-collar work in the form of specific tasks. Regardless of how we describe the present, be it the digital epoch, the Fourth Industrial Revolution era, or the “second machine age”, what it boils down to is that all work that requires supervision is being outsourced to robots and algorithms. Non-standard, creative, experimental work, on the other hand, doesn’t naturally lend itself to management.

The second fundamental shift we see now is that a strategy of making a plan and then executing it is no longer viable. What used to be known as “muddling through” is now seen as adapting to the fast-changing environment. Strategy, as we know it, is dead. Dealing with uncertainty is the number one challenge and, as the cliché goes, it’s the number one opportunity too. If your company isn’t the disruptor, it’s a clear sign that it’s about to be disrupted.

The bottom line is that the hierarchical management mode is no longer suited for the challenges of the modern economy. Every pillar of a traditional organization is now in flux, as was brilliantly conceptualized by Tanmay Vora.

The status quo is often protected by the vocabulary of business: directors direct, presidents preside, and managers manage. But all those activities are adding much less value than they used to be. They constrain innovation and stifle creativity in the pursuit of order.

Contextual awareness, peripheral vision, design thinking and a multi-disciplinary approach – these are all terms that are trending in modern office-speak. And deservedly so. A project-based and titles-free organization — where yesterday’s team member is today’s team lead — can deliver the flexibility and agility that businesses yearn for.

“Context Curator” is the term I’d like to introduce to the business dictionary. To lead a project is not to assign tasks and monitor performance, but to empower, to define the broader context, and to organically link the work of one team with the rest of the business. Following the example of Netflix and striving for higher talent density is only half the battle. Curating the context in which high performers can excel – rather than attempting to manage them – is the key to unleashing their full potential.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Entrepreneurship

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.