How Africa and Asia are joining forces on universal healthcare

Thailand's successes in rolling out UHC has led to a knowledge-sharing partnership with ambitious Kenya. Image: Reuters/Sukree Sukplang

Sofiat Makanjuola-Akinola

Director, Health Policy and External Affairs, Roche Diagnostics Solutions, Roche

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

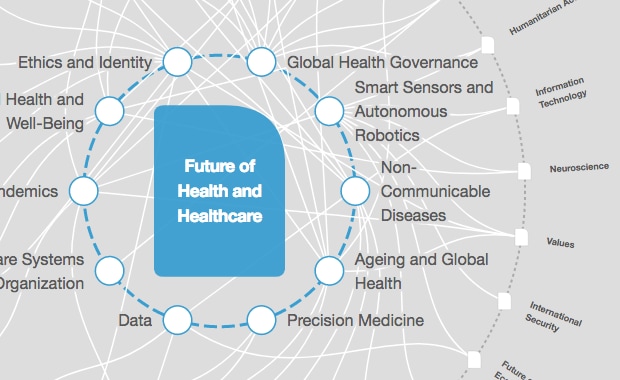

Health and Healthcare

An estimated 400 million people in the world lack access to basic health services, while millions are pushed into extreme poverty each year because of out-of-pocket healthcare costs. The burden of this lack of universal health coverage (UHC) is largely placed on Africa and Asia, where 97% of the population are impoverished by out-of-pocket health spending. These regions have the fastest increase in populations facing catastrophic health expenditures (defined as having to spend 30% or more on health products and services). In Africa, an estimated 11 million people fall into poverty every year through using their household income to access healthcare services, medicines and products.

Universal health coverage is about ensuring that all individuals and communities have access to the healthcare they need without suffering financial hardship. Ensuring UHC, however, does not mean that healthcare services will always be at no or low cost – simply that out-of-pocket payments will not be a deterrence from accessing care, or a cause of financial hardship.

The inclusion of the target of achieving UHC in the UN's Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals was a milestone in recognizing health as a human right, and represented a commitment to addressing inequalities and exclusion. UHC is both a target and enabler of the achievement of other targets. It not only contributes to achieving Sustainable Development Goal #3, “Good health and wellbeing”, but is also linked with SDGs such as #1, “Poverty eradication”; #8, “Decent work and economic growth”; and #10, “Reduced inequalities”.

Accordingly, achieving UHC has become a prime focus of global institutions such as the World Health Organization, which aims to provide a billion more people with UHC by 2023, and the World Bank, which has made UHC a cornerstone of its twin goals of ending extreme poverty and increasing equity and shared prosperity.

In Africa and Asia, there has been a recognition of the importance of partnership among governments, civil society and the private sector in advancing UHC. The two regions have begun to cooperate in making use of a global south perspective on how to achieve UHC. Here are examples of how this has worked so far:

When President Uhuru Kenyatta announced his big four action plan for Kenya last year, UHC was on that list. A pilot programme was launched in December 2018 to focus on four counties with high disease burdens – Kisumu, Nyeri, Machakos and Isiolo – and will offer free basic healthcare services to residents under the age of 18, with the aim of reaching 3.2 million people, before scaling up nationwide.

The Kenyan government has set itself a goal of 2022 for its far-reaching aims. To speed the process, it has formed a knowledge-sharing partnership with one of the few developing world countries that has successfully implemented UHC in the past: Thailand.

Three decades ago, the South-East Asian nation began the gradual introduction of universal healthcare coverage – first for the poor, then for the near-poor, as well as children, older people and formal sector employees. By 2000, Thailand had reached 71% coverage, but 17,000 children under five were still dying a year, many from preventable diseases.

In 2001, it made a quantum leap with the election of a new government that implemented the Universal Coverage Scheme. Today, every Thai citizen has the right to a comprehensive health package, largely funded by a general income tax. As a result, infant mortality is down, worker health is up, and once-devastating health expenditures for families have been significantly reduced. The Thai model, meanwhile, is commendable for being locally initiated and financed, making it independent of donor resources.

From 2019-21, Thailand will serve as an advisory and technical partner to Kenya in its bid to implement UHC. Already, more than 50 Kenyans have been trained evidence-based decision-making for the health sector by Thailand’s Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Programme. The partnership will enable Kenya to take giant steps towards achieving UHC sustainably, and also enable knowledge transfer to other countries in the region.

One other enabler for Kenya has been the implementation of innovative financing models, such as the Managed Equipment Services (MES), designed by GE Healthcare. As one of the largest public/private risk-sharing projects of its kind in healthcare to date in Africa, Kenya’s $450m MES model is designed to provide staff and patients at the country’s public hospitals with access to the latest medical technologies, services and skills development.

The project represents a new model for healthcare infrastructure modernization in Africa, bringing together implementation partners, lenders, insurers and advisory services in the creation of a new model for risk/reward-sharing and credit underwriting for big healthcare infrastructure-project financing.

With this approach, Kenya will be able to budget healthcare expenditure over several years by deferring upfront capital outlays. This helps ensure that health budgets remain nimble, and that the Ministry of Health can continue to allocate critical funds towards the most pressing health challenges.

In February, Egypt’s Ministry of Health and the Japan International Cooperation Agency held a third seminar, with the African country looking for advice on how to to implement a UHC system of its own.

The seminar explored Egypt’s new health insurance law, with discussion on obstacles to UHC implementation and how to overcome them. A country like Japan, which achieved universal health-insurance coverage in 1961, can provide invaluable insight on aspects such as equity in access and the requirement for ongoing adjustments. In Japan, for instance, concerns over an ageing population have forced the restructuring of healthcare and establishment of a fund for the elderly.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to achieving UHC, and all countries must make progress towards the UN’s goal in their own way. However, partnerships and knowledge-sharing are proving themselves to be great great pathways towards helping countries learn and avoid common pitfalls on their road to health coverage for all.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Shyam Bishen and Annika Green

April 22, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 17, 2024

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024

Fatemeh Aminpour, Ilan Katz and Jennifer Skattebol

April 15, 2024

Carel du Marchie Sarvaas

April 11, 2024