For the economy to cope with an ageing population, we must identify new solutions – here's how

Image: Vlad Sargu/Unsplash

David E. Bloom

Clarence James Gamble Professor of Economics and Demography, Harvard School of Public HealthPopulation ageing, driven by declining fertility, increasing longevity, and the progression of large-sized cohorts to older ages, is the dominant global demographic trend of the 21st century. This column introduces a new Vox eBook that examines the myriad challenges and economic uncertainties posed by ageing populations. Overall, the contributions suggest that although the challenges are formidable, they are not insurmountable. There is good reason to reject the view that ‘demography is destiny’.

Population ageing is the dominant global demographic trend of the 21st century. Never before have such large numbers of people reached the older ages (conventionally defined as ages 65 and up). It took the world over 99% of human history, until roughly the year 1800, to reach a total population of 1 billion, and we now expect to add 1 billion older individuals in just the next 35 years. This sizable accretion will arrive on top of 700 million older people currently living on the planet. The net effect of these shifts is that by 2050, older people will outnumber adolescents and young adults and represent more than double the number of children under five (United Nations 2019). Notably, the size of the 85+ crowd – the so-called oldest old, whose needs and capacities tend to differ significantly from those who are merely old – is growing especially fast and is projected to surpass half a billion in the next 80 years.

A new Vox eBook examines the myriad challenges and economic uncertainties posed by ageing populations (Bloom 2019). The chapters in the first part of the eBook deal with the implications, or the 'so what,' of population ageing. The chapters in the second part of the eBook offer some potential public and private policy solutions (the ‘now what’). In this column, I preview the eBook and also provide some background on the drivers and scale of population ageing (the ‘what’).

The what

Population ageing is driven by three principal forces: declining fertility, increasing longevity, and the progression of large-sized cohorts to older ages. These three forces operate with different strengths in different country groups and over different time frames. But it is the relatively certain progression of large-sized cohorts to the older ages that will make the most significant contribution to future population ageing. For this reason, demographers are more confident in their projections of population ageing than in many other variables they routinely project, such as rates of fertility and population growth.

Although every country in the world will experience population ageing, there will be considerable cross-country heterogeneity in the speed of this phenomenon. For example, Japan is currently the world leader with 28% of its population aged 65 and over, triple the world average and more than 20 times the share in the United Arab Emirates, which anchors the bottom of the country list.

The so what

The ubiquity and force of population ageing have led economists to express concerns. At a high level, these concerns relate to the prospect of (1) workforce shortages as retirees come to outnumber new entrants to the workforce; (2) asset market meltdowns and a drop in the savings rate as older people liquidate their assets and dissave to support themselves; (3) economic growth slowdowns due to labour and capital shortages; and (4) fiscal stress, due for example to rising healthcare costs owing to the fact that diseases of old age – including cancer, chronic obstructive respiratory disease, heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias – are very expensive to treat, not just medically but also in terms of requirements for formal and informal care.

The logic behind some economists’ concerns with population ageing is that there are strong life-cycle patterns to production and consumption and that older people simply do not produce as much as they consume. The effects of these life-cycle patterns are plausibly large. For example, in economic terms, the value of lost production due to morbidity and mortality from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) – coupled with the effect of diverting a portion of savings to cover treatment costs – is equivalent to a roughly 3-10% tax on GDP based on a macroeconomic model calibrated for selected countries out to 2050. That is the same order of magnitude as HM Treasury’s estimated 4-9% effect of Brexit on the size of the UK economy.

Further honing in on concerns about the labour force, economists have found that provision of informal caregiving for the elderly reduces formal employment among working-age adults, negatively impacting GDP growth in the US. With respect to rising healthcare costs, large fiscal adjustments may be necessary if costs continue to rise more rapidly than per capita GDP. The US, for example, may face a difficult choice between increasing tax rates and shrinking or eliminating Medicare and Medicaid. Emerging evidence also suggests that populations become more risk averse as they age, which can result in a decreased appetite for entrepreneurial activity.

At the aggregate level, population ageing is likely to have effects on savings, investment, real interest rates, and international capital flows. In fact, population ageing could drive capital flows from the more- to the less-rapidly ageing countries, leading to consequences for countries’ and regions’ financial health and the global distribution of economic power. Some economists argue that ageing-related long-term fiscal problems will be more severe in the US than in Western Europe, China, Japan, and South Korea. This suggests that ageing may play a nontrivial role in shifting the cross-country distribution of economic performance.

While there are undoubtedly many economic risks associated with population ageing, we must avoid the pitfall of overstating population ageing’s challenges by underestimating the productive contributions that older adults make to society. For example, even when older people are not working for pay, they often engage in non-market activities that create value, such as caring for grandchildren, undertaking volunteer work, or working around the house.

Perhaps the biggest source of uncertainty here has to do with whether population ageing simply involves adding years to life, or also involves adding life to years. That is, will increased longevity translate into more years of misery and suffering, as we spend more years unable to autonomously perform the normal activities of daily living such as eating, bathing, dressing, grooming, and going to the toilet? In this grim scenario, the state would be burdened with larger and more persistent healthcare and pension liabilities without offsetting tax receipts.

Alternatively, are we living longer with minds and bodies that are also becoming more robust and resistant to decay? Under this circumstance, older adults are able to be productive and function independently for longer periods as life expectancy rises. As such, increased longevity would represent a bona fide improvement in human welfare and a potential boon to governments in terms of tax receipts relative to social spending. From a social, economic, fiscal, political, and humanitarian point of view, it is hugely consequential whether increased longevity is accompanied by a compression or an expansion of the morbid years. Unfortunately, debates related to the compression/expansion of morbidity remain unresolved, with the extant analyses nowhere near pointing to a consensus.

The now what

The good news is that there are many options for addressing challenges associated with population ageing. These include institutional adaptations and policy reforms related to health and long-term care and its finance, innovation of new technologies and designs, increased human capital investment throughout the life cycle, and changes in business and human resource practices.

Solutions to the macroeconomic consequences of population ageing include reimagining the way we deliver and finance healthcare. In India, for example, recent public sector initiatives to provide expanded hospital coverage to the poor could be shored up by additional measures to effectively address the growing health burdens associated with population ageing. These include a commitment to significantly higher public funding for health than in the past, improved targeting of households containing the elderly, and efforts to address the serious shortage of medical personnel that currently exist in primary care settings. As another example, health insurance in the U.S. could be improved by increasing the efficiency through which enrolees benefit from cost savings achieved through less expensive forms of Medicare coverage.

Social insurance and pension reform are also highly relevant. Encouraging longer careers by raising retirement ages would generate more private resources for retirement and more income tax revenues for government support. Reliance on non-contributory means-tested pensions could also be increased. Of course, such policy reforms are not uncontroversial. Policies that help cohorts currently entering the labour market plan for their retirement, such as pension auto-enrolment, also have a role.

Determining the best policies for addressing the challenges of population ageing will require investment in data collection and research. For example, achieving a better understanding of the economic value of investments in increased longevity and healthy ageing would have considerable social value.

Although the challenges associated with population aging are indeed formidable, they are not insurmountable. In other words, there is good reason to reject the view that ‘demography is destiny’. Indeed, history shows, and common sense and logical reasoning confirm, that demographic change has a natural and persistent tendency to spur behavioural changes, technological and institutional innovations, and policy reforms that either accentuate favourable demographics or offset negative ones.

This is what ensued when the world population was doubling from 3 to 6 billion between 1960 and 2000. Many dire predictions were made, and they garnered great attention, but the reality is that global income per capita more than doubled during that time frame, life expectancy increased by more than 15 years, and primary school enrolment rates approached universality in many countries.

Population ageing indisputably poses myriad challenges, but there are also myriad potential solutions. The task before us is to figure out which are best to adopt, individually and collectively, and to mobilise the political and social will and the financial muscle to act proactively as we sail into uncharted demographic waters.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

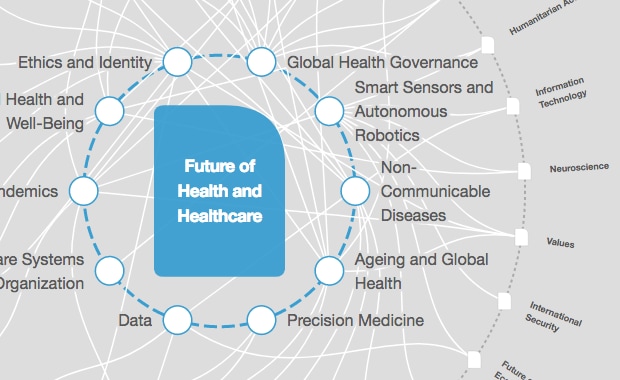

Health and Healthcare

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Guiseppe Saba

November 7, 2024