3 charts that helped change coronavirus policy in the UK and US

The US and UK have both introduced measures to stop the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, including social distancing. Image: REUTERS/Simon Dawson

- The UK and the US have ramped up efforts to "flatten the curve" of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- It follows the publication of a scientific report modelling the effectiveness of different interventions to limit the spread of the virus.

- The report concludes that a strategy of "suppression" would be better than "mitigation" to reduce deaths and prevent healthcare systems being overwhelmed.

- Suppression involves a combination of four interventions: social distancing of the entire population, case isolation, household quarantine and school and university closure.

- But when these measures are relaxed, the modelling predicted cases would rise again, so interventions may need to be in place until a vaccine is developed - 18 months or longer.

In his first daily press conference on the coronavirus pandemic on 16 March, the UK's Prime Minister Boris Johnson outlined a raft of new key measures to curb the spread of infection, saying "drastic action" was needed.

They include avoiding gathering in public places, working from home where possible, everyone in a household self-isolating for 14 days if one person gets sick, and the over-70s and most vulnerable minimizing social contact.

At the same time, the White House released new guidelines urging Americans to avoid gatherings of more than 10, to work from home, only shop for essential items and stop eating in restaurants.

States across the US have ordered sweeping restrictions - including New York closing all restaurants, theatres and casinos.

Helping to drive these stepped up COVID-19 responses from both countries is a report from London's Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, which models the impact of different non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) on the number of deaths and the healthcare system.

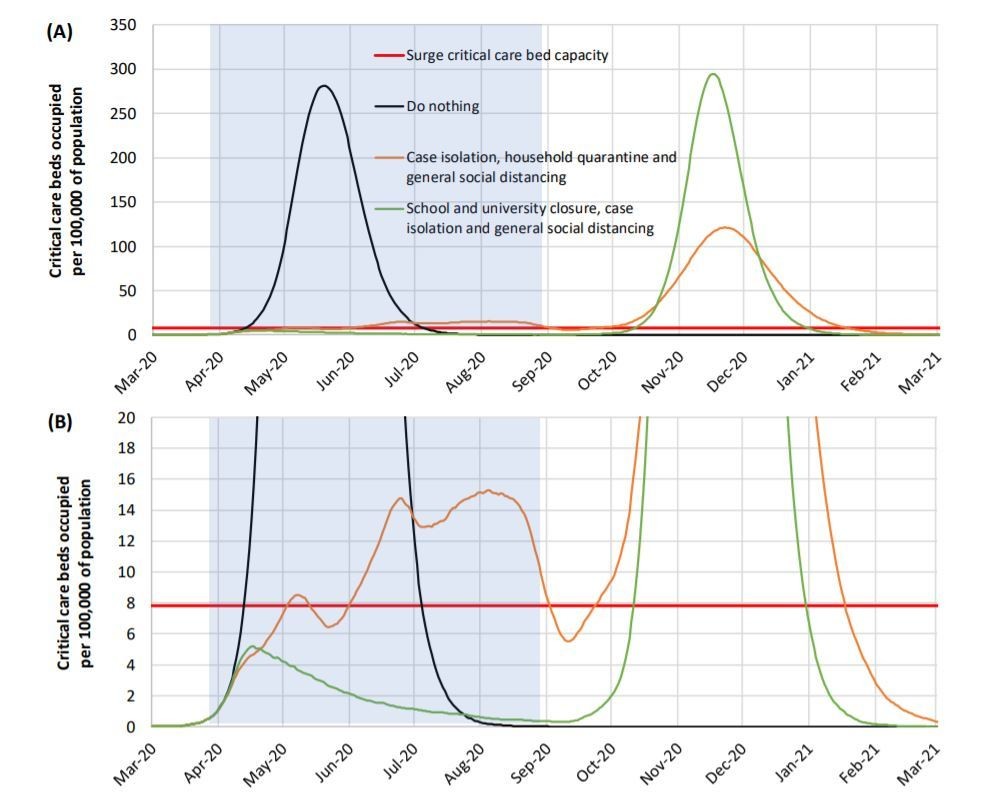

These three charts show the impact of doing nothing, compared to taking more drastic action, according to the report, which has not yet been peer-reviewed.

1) 'Do nothing'

In this worst-case scenario, there are no interventions or changes in people's behaviour. The Imperial College scientists predict the number of deaths would peak in each country three months after the first coronavirus infections were discovered.

Based on each person infecting another 2.4 people (the R0 or reproduction number), they predict approximately 81% of the populations of both countries would be infected, resulting in 510,000 deaths in Great Britain and 2.2 million in the US.

The peak is higher in Britain due to the older population and occurs later in the US because of the larger geographic scale.

What is the World Economic Forum doing about the coronavirus outbreak?

These estimates don't account for indirect deaths, where people don't receive treatment for unrelated health conditions due to the healthcare systems being overwhelmed.

However, the report notes that: "Epidemic timings are approximate given the limitations of surveillance data in both countries."

Crucially, they predict that in this scenario, demand on intensive care beds would be 30 times greater than the availability, with capacity "exceeded as early as the second week in April".

2) Mitigation vs suppression

To find the best-case scenario for reducing the number of deaths and impact on the hospitals, the report modelled two different strategies for dealing with the outbreak in both countries.

- Mitigation: Focuses on "slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread – reducing peak healthcare demand while protecting those most at risk of severe disease from infection".

- Suppression: Aims to "reverse epidemic growth, reducing case numbers to low levels and maintaining that situation indefinitely".

While both strategies pose challenges, the scientists found that mitigation measures (home isolation of those with symptoms and others in the household and social distancing of the elderly and vulnerable) would reduce deaths by half and peak healthcare demands by two-thirds.

But the outbreak would still result in 250,000 deaths in Britain, and 1.1 to 1.2 million in the US, with the 'surge capacity' of intensive care units overwhelmed "at least eight-fold".

The report notes that, in the UK, this conclusion has only been reached "in the last few days", based on the demand for intensive care beds experienced in Italy and NHS information.

Suppression involves combining four interventions to "flatten the curve" for a five-month period. It's predicted to have the biggest impact, but stops short of a total lockdown.

The scientists said: "Our projections show that to be able to reduce R to close to 1 or below, a combination of case isolation, social distancing of the entire population and either household quarantine or school and university closure are required."

Around three weeks after the combined interventions are introduced, the scientists predict there would be a reduction in the peak need for intensive care beds - and this would continue to decline while the policies stay in place.

However, once the interventions are relaxed (around September in the above chart), the infections would begin to rise again, leading to a predicted peak epidemic later in the year.

3) A cycle of suppression and relaxation?

According to the report, successful temporary suppression now would lead to a larger epidemic later in the year "in the absence of vaccination, due to lesser build-up of herd immunity".

The major challenge with such rigorous suppression measures, say the scientists, is that because the virus starts spreading again once they're relaxed, they would need to be kept in place until a vaccine becomes available, which could be more than 18 months away.

In the chart above, they show that we could enter a cycle of "intermittent social distancing", responding to rises in cases, when the measures would need to be reintroduced.

The report says China and South Korea show that suppression is possible in the short term, but notes: "It remains to be seen whether it is possible long-term, and whether the social and economic costs of the interventions adopted thus far can be reduced."

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

COVID-19

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Mansoor Al Mansoori and Noura Al Ghaithi

November 14, 2025