Italian coronavirus pressures and flattening the curve – an epidemiology expert explains

So far, Italy has had 31,506 confirmed cases and 2,503 deaths. Image: REUTERS/Flavio Lo Scalzo

Explore and monitor how COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

COVID-19

- Italy has one of the oldest populations in the world.

- It has been struggling under the pressure of coronavirus.

- Some places have succeeded in flattening the curve.

Per head of population, Italy is the world’s worst-affected country in the COVID-19 pandemic. For every 1 million Italians, there are 521 confirmed coronavirus cases.

As of 18 March, Italy has had 31,506 confirmed cases and 2,503 deaths. The question on many people’s lips has been: why has Italy suffered such heavy losses?

Jennifer Dowd is Associate Professor of Demography & Population Health at the University of Oxford, and Deputy Director of the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science. This is her view on why Italy has experienced a very high COVID-19 death toll, as explained on Twitter.

Although there are always going to be many variable factors involved in cases of viral infection, one has risen to prominence when it comes to explaining the current situation in Italy: Italy’s older population structure, she says.

Age-related pressures

Italy has the second-oldest population in the world. In 2019, the average age in the country was 45.4 years, which is about two years older than in 2011. In Liguria (the region around Genoa, in the north of the country) the average age is 49.1 years. But further south, Campania (the region around Napoli) has an average age of 43, making it the youngest place in Italy.

“COVID-19 fatalities are hitting older age groups hard,” Dowd says. Fatality rates for confirmed cases among the 80- to 90-year-old age bracket are currently 17.5% in Italy, which Dowd describes as "frighteningly high."

Consequently, she says, those countries with older populations are likely to record a higher case-fatality rate than those with younger populations. This also places national healthcare services under pressure. A lot of people falling seriously ill in short succession can leave hospitals overwhelmed by factors including too many desperately ill people, too few ventilators, not enough doctors, nurses or hospital beds.

As intensive care facilities struggle to keep up with demand, the risk of fatalities increases.

Professor Dowd also explains that despite adjusting the assumptions in mathematical models of the spread of COVID-19, “the tight relationship between population age structure and total deaths remains”.

Flattening the curve

Countering these effects calls for a targeted drive to reduce the pressure on health services. If those most likely to become severely ill are the ones most shielded from infection, not only are they less likely to fall victim to COVID-19, but the burden on hospitals and medical facilities can be alleviated, too.

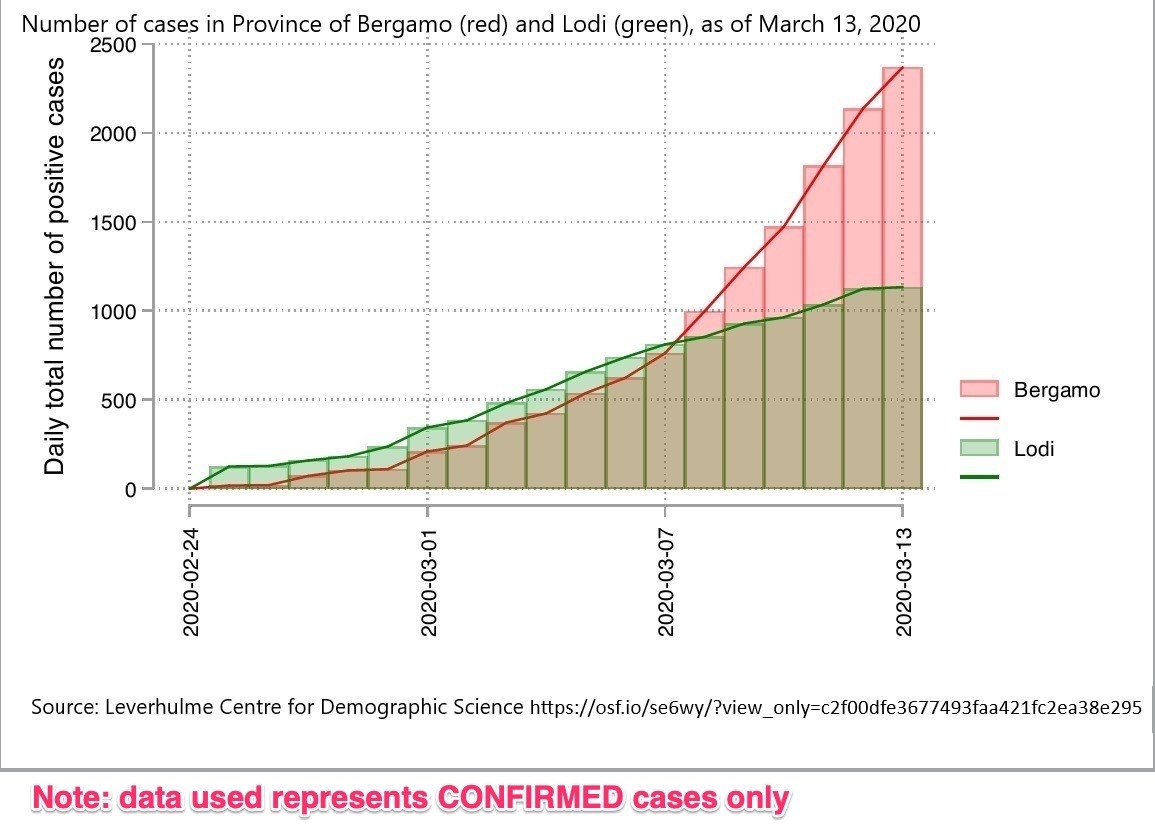

The city of Lodi, around 40 kilometres south-east of Milan, stands out as an example of how this can work, Dowd says. Unlike other parts of northern Italy, Lodi implemented a strict lockdown early in the course of the outbreak. When compared with other cities, the effects of that early intervention are clear: cases did not increase as quickly as in other parts of the country.

There is another factor which may have put Italy’s older people in jeopardy, Dowd suggests. The country is famous for the central role of extended families in people’s daily lives. But this intergenerational mixing may have played a part in spreading the infection. Again, she points out, understanding such effects can help predict future infectious disease outcomes.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Shyam Bishen

April 24, 2024

Shyam Bishen and Annika Green

April 22, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 17, 2024

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024

Fatemeh Aminpour, Ilan Katz and Jennifer Skattebol

April 15, 2024