We need more urban innovation projects like the 'Google City'. This is why

Urban experimentation - like Sidewalk Labs' smart city - is needed today more than ever. Image: REUTERS/Chris Helgren

- Sidewalk Labs, owned by Google's parent company Alphabet, has pulled out of a new, large-scale urban development in Toronto;

- How we test digital innovation in a physical space is a huge challenge and attracts both critics and risks;

- Without lots of experimentation, led by start-ups, however, we will not drive urban innovation forward or find a path to healthy urban futures.

One of the lesser-known casualties of COVID-19 is a new, large-scale urban development in Toronto led by Google’s sibling company, Sidewalk Labs. Several years in the making, the “Google City”, as it is sometimes called by the media, has ultimately come to a halt because of the ongoing recession.

Public perception has, however, stymied the development’s entire lifespan with some activists labelling it an “800-acre surveillance state”. While little-talked about, the failure of this project is sad news – urban experimentation is needed today more than ever.

The project had an upbeat start. At its launch, CEO Dan Doctoroff suggested the experimental neighbourhood could address “costs of living (...) congestion (...) [and] climate change”. Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau said: “I have no doubt Quayside will become a model for cities around the world.” The plan was to transform Toronto’s Quayside waterfront into an 800-acre experiment for high-tech, smart cities. Robots would serve as taxis and trash collectors; apartments would be made from affordable, renewable materials; and an array of sensors would optimize everything from the timing of traffic lights to the configuration of public space.

The subsequent years were not a smooth ride. The COVID-19 recession was the last straw for a project that has been challenged every day since its first press conference, particularly on issues of privacy and data ownership. I sat on the advisory committee for the Quayside development and witnessed both its promise and its uncertainty. Although the public concerns about the project have been absolutely legitimate, I believe the end of the Quayside project is ultimately a loss not only for Sidewalk Labs but also for Toronto and for the greater cause of urban innovation.

Ever since humans started living together in large numbers, the city has been a critical site for social experimentation. Medieval Italian city-states, such as Venice and Genoa, were critical experiments in the history of democracy; while the phalenstѐres proposed in 19th-century France by the philosopher Charles Fourier brought forward the then-radical ideas of minimum wages and women’s rights. In the 1980s, a “special economic zone” in Shenzhen, China, stimulated a historic economic boom. The success of Shenzhen, where a liberalized economy attracted foreign investment and spurred economic growth, helped reformers justify nationwide changes. According to US economist Paul Romer: “Without Shenzhen, reform in China might have stalled before it had a chance to take hold.”

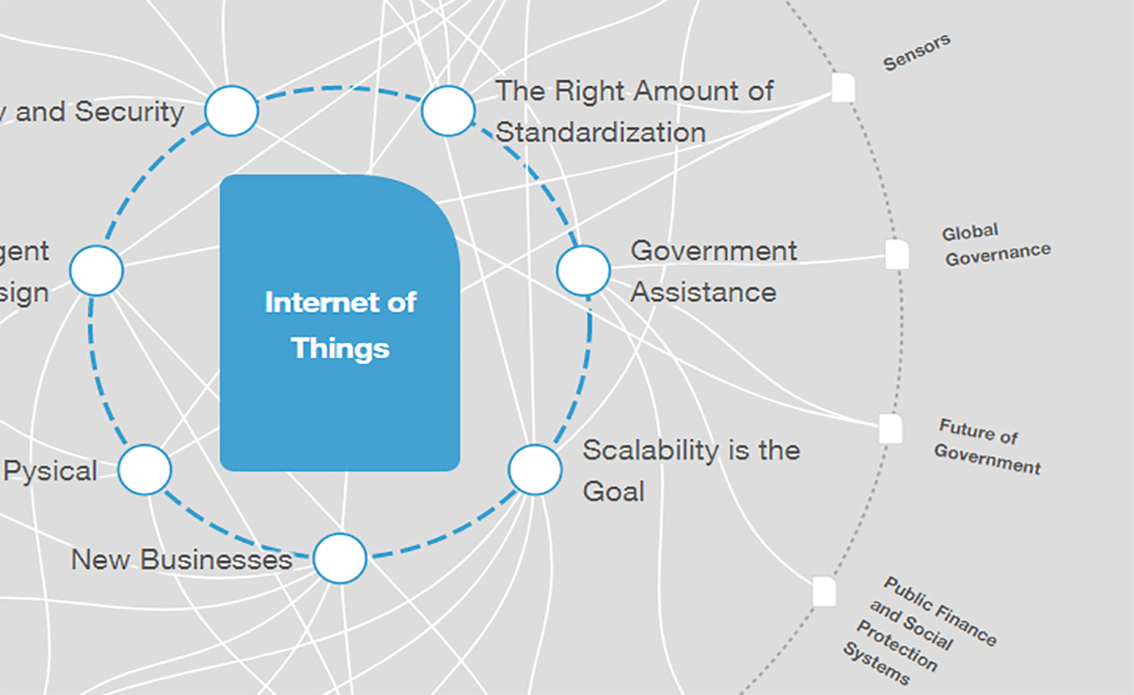

Urban innovation is particularly necessary today, as the Internet of Things spearheads a new wave of experimentation. We are entering the era of smart cities, in which information and communication technologies capture extraordinary amounts of data and deploy their findings, often in real-time, to transform economic and administrative practices.

An array of start-ups that blend the physical and digital, what Richard Florida calls “urbantech” companies, lead the smart city movement. Facial recognition, cell phone tracking and self-driving cars raise tremendous ethical issues. We must then try out a variety of different approaches, from the public and private sectors, for how to best incorporate these technological advancements into our lives. We are in a similar place to the early 2000s, when experimentation with the first wave of digital innovations led to the selection of champions that have now changed our lives, including Google, which is itself attempting to transition into urbantech.

The crucial difference between this moment and the earlier phase of the digital revolution is how we test digital innovation in physical space. The failure of an app is one matter, but the collapse of an urban experiment is a different story. Even apparently innocuous technologies can have unexpected consequences. Since 2017 in China, several unicorn start-ups tried to push the vision of renting a dockless bike through a mobile app. As their plans struggled to get in gear, massive “bike cemeteries” grew in vacant lots across the country. Such failures are all but inevitable; a multiplicity of innovations and mutations in urban technologies helps to select the winners of tomorrow and counteract the risk that any one idea might fail.

Interestingly, in the case of Toronto, activists were less concerned about the risks of failure than the risks of success; they feared that Sidewalk could exploit their land, their economy, and their privacy. Author and #BlockSidewalk activist Cory Doctorow wrote: “[A]s a dystopian science fiction writer (...) it is obviously a terrible idea to let vast, opaque multinational corporations privatize huge swathes of our city.” As Sidewalk struggled to maintain transparency and trust, the community’s concerns compounded.

Neither the risks nor the critics of Sidewalk’s plans should be blamed for the end of the Toronto project; both are invariable, necessary parts of experimentation. What Sidewalk lacked was a robust platform for civic discussion, one that would have allowed the city to manage its risks and build trust with its citizens. The back-and-forth between the activists and the company was a confrontation, not a dialogue, and this posturing decimated political consensus by default. True city-making is the art of bringing different voices together. The physical space, what the ancient Romans called the urbs, only results from the cooperation of its people (civitas). In an open forum, participants can correct problems as they occur.

Improving platforms for community involvement is a formidable challenge and yet another example of why we must continue to create new experiments for urban innovation. The more different attempts we make, the more likely it will be that we can strike a healthy balance in urban life. Some efforts will fare better than others, which is why it is so important to commit to a broad range of projects. Companies, governments and communities the world over should follow this example, leaving no stone unturned. We need more Google cities, more Linux cities, more cities remade by start-ups that no one has heard of yet or, crucially, by communities of citizens ready to take action. Some will and should fail, which is why we need as many ideas as we can imagine for our common urban future.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Internet of Things

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Urban TransformationSee all

Kalin Bracken and Sam Chandan

December 10, 2024