Is this the secret to surviving in a fractured world?

For young people, learning to be optimistic may be the best defence against job uncertainty. Image: REUTERS/Sergio Moraes

The future of jobs has never been more uncertain. McKinsey Global Institute estimates that half of all jobs could be automated by 2055. Industry-wide disruptions are occurring faster than ever before. Artificial intelligence and robotics threaten the livelihood of even creative and highly educated professionals. School curricula are unable to keep up with the rapid change in job skills.

In addition to increasing uncertainty about the future of jobs, we live in a fractured geopolitical world: global distrust of industry leaders, elected officials, elections, and entire political systems is at an all-time high. Young people, especially, are frustrated with their political leaders, due to perceived corruption, insincerity, and lack of accountability.

It’s no wonder that depression is soaring among young people, from China and India to the United States and the UK. At the apex of uncertainty and a fractured world, how do we avoid developing an entire generation of pessimistic, unemployed youth?

The soft skills gap

The World Economic Forum’s Closing the Skills Gap Project, an ongoing discussion among leaders from the public sector, private sector, and civil society, seeks to solve the disconnect between education systems and the critical skills needed for the future. Talk about a skills gap isn’t new, of course. But, more and more, the conversation is shifting to a recognition that the skills gap cannot be resolved only through technical and vocational skills. It’s not a simple matter of offering coding classes for kids or providing reskilling programs for the unemployed. Soft skills are critical to bridging the gap.

Consider a few examples. Google’s Project Oxygen studied the qualities of its top employees, and found that a full seven soft skills ranked higher than technical expertise:

• Be a good coach

• Empower your team and don’t micromanage

• Express interest in team members’ success and personal wellbeing

• Be productive and results-oriented

• Be a good communicator and listen to your team

• Help your employees with career development

• Have a clear vision and strategy for the team

The Asia Society’s Center for Global Education agrees, citing seven soft skills that are critical for young people to become adaptable adults:

• Critical thinking and problem-solving

• Collaboration and leading by influence

• Agility and adaptability

• Initiative and entrepreneurialism

• Good oral and written communication skills

• Accessing and analysing information

• Curiosity and imagination

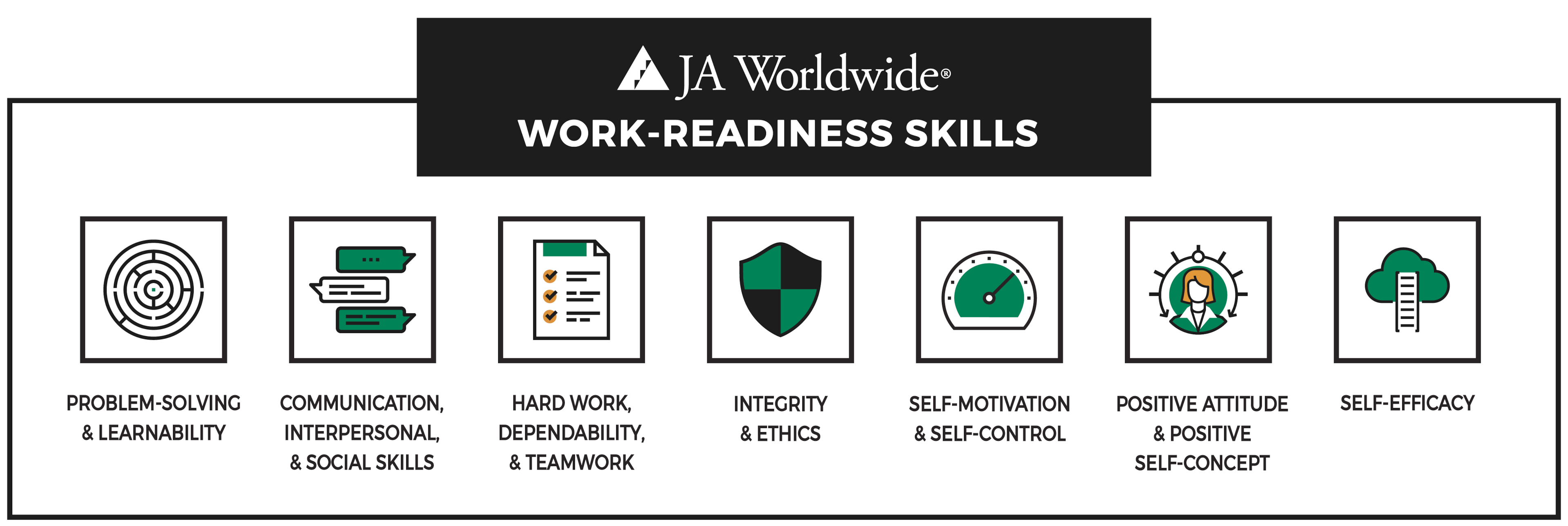

At my own organisation, JA (Junior Achievement) Worldwide, we worked with Accenture to identify the soft skills that our programs teach in our three areas of concentration: work readiness, financial literacy, and entrepreneurship.

Shifting mindsets

Inculcating soft skills in young people ultimately involves a shift in mindset, from one of “I can’t” to “I can”; from “these are my limited skills” to “I’ll keep learning and growing throughout my career”.

This shift is related to a number of concepts, from Carol Dweck's “growth mindset”, Angela Duckworth's “grit”, and a number of researchers studying “resilience” in young people, to my own organisation’s focus on “self-efficacy” (the belief that you will eventually succeed, in spite of setbacks and disappointments along the way).

All these mindset shifts are rooted in optimism and the positive psychology movement. Martin Seligman, whose ground-breaking research in the late 20th century showed that optimism can be taught, found a direct correlation between optimism and resilience. Patrick Steinfort found that optimism and grit together predicted better sports performances. And Albert Bandura found that turning negative thoughts into positive thoughts is one of the critical elements of developing self-efficacy. Individual optimism – the tendency to expect positive personal outcomes – is key.

Human nature causes us to be individual optimists and social pessimists – that is, optimistic about our personal futures, but pessimistic about the country’s or world’s future. But imagine, instead, a world in which young people are individual pessimists, believing that their own futures will be bleak. Imagine a world in which the optimism of youth starts to fade as they’re faced with the reality of high youth unemployment and a fractured geopolitical world.

That world is coming sooner than we think. Millennials in the Western world already believe they will be less happy and less financially successful than their parents. We need to intervene early, teaching optimism to young people before individual pessimism takes hold.

Teaching optimism

Fortunately, a movement within both the education and positive psychology fields recognises the benefits of learning optimism in the early years of education.

At the Center for Curriculum Redesign (CCR), a global nonprofit exploring what students need to learn for the 21st Century, Charles Fadel says that schools around the world have been tweaking their curricula, but “they have never been completely redesigned for the comprehensive education of knowledge, skills, character, and meta-learning – the four dimensions of education defined by the CCR”. That final category – meta-learning – refers to how young people reflect and adapt. That’s the framework for learning optimism.

Alejandro Adler, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote his dissertation on how to teach wellbeing at scale in Bhutan, Mexico, and Peru. He found that teaching life skills (such as mindfulness, creative thinking, and empathy) to students in grades 7–12 had a profoundly positive impact on students’ ability to learn.

In Academic Optimism of Schools: A Force for Student Achievement, Wayne Hoy, John Tarter, and Anita Woolfolk Hoy discuss how to teach academic optimism in schools. According to Wayne Hoy, “Optimism is the overarching theme that unites efficacy, trust, and academic emphasis because each of these elements contains a sense of the possible”.

At the International Positive Education Network, scholars are bringing together schools, non-profits, corporations, government agencies, and parents to promote positive education, collaboration, new educational practices, and new government policy.

Whether through local schools, NGOs working in tandem with schools, or parent interaction at home, fostering optimism in young people and developing social and environmental skills is critically important, even at the expense of core academic skills. Some schools have made this trade-off or diverted resources to social and environmental learning programs, but we have a long way to go to bring soft skills to the centre of the modern curriculum. We need youthful optimism to deliver hope for a better future.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Values

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Jobs and the Future of WorkSee all

Neeti Mehta Shukla

February 27, 2026