We asked leaders at Davos 2026, how can we unlock new sources of economic growth? Here's what they said

Deep dive

Global Economic Outlook session at Davos 2026. Image: World Economic Forum

- The world economy has withstood a year of shocks remarkably well, but some signs of strain are showing, a range of economic experts told Davos 2026.

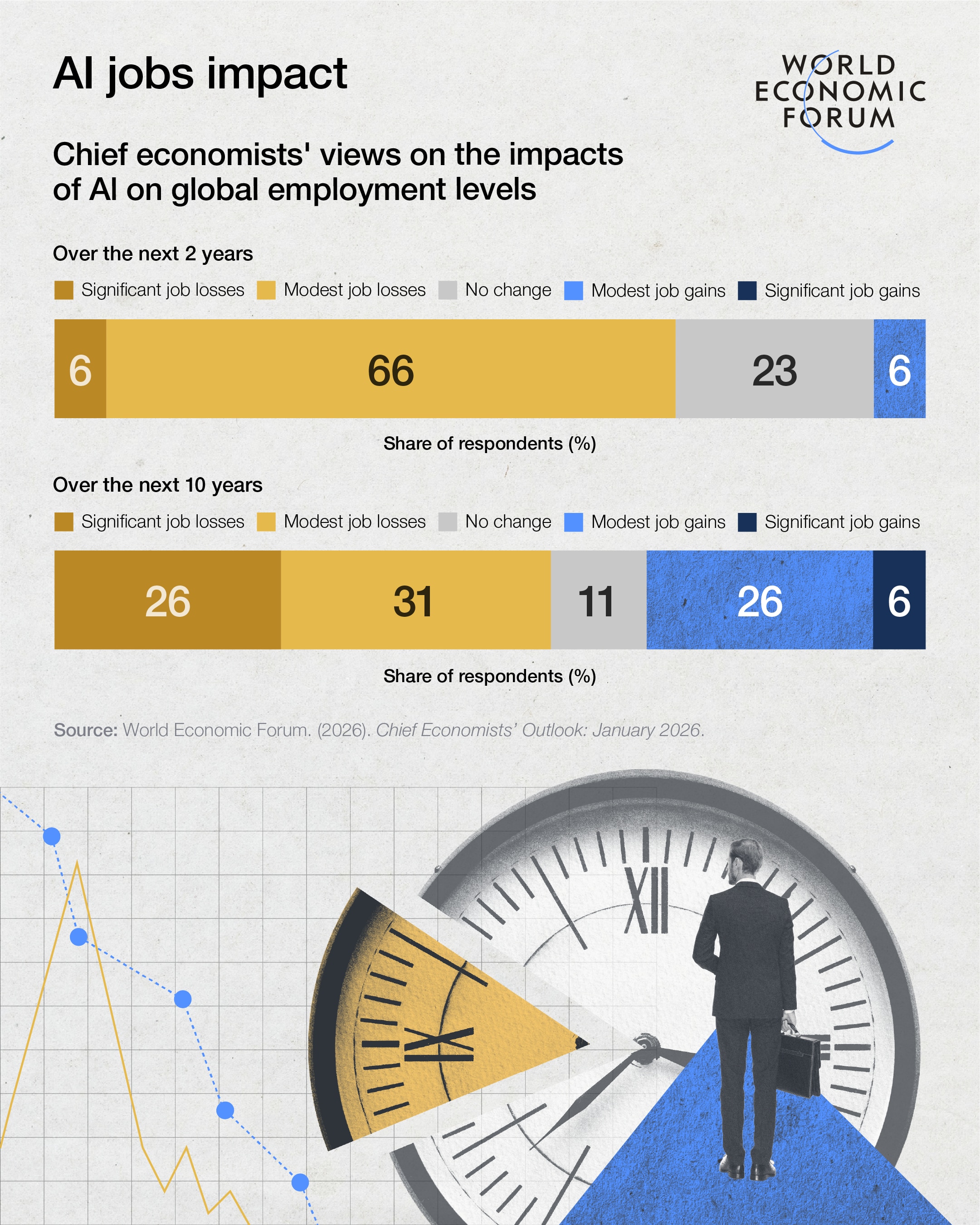

- They see AI as holding huge potential to power a much-needed boost in productivity, but say there are also risks for the job market, particularly for young people.

- Public debt burdens are becoming more concerning amid demographic changes, and could leave public spending too stretched to handle unexpected shocks.

After a year of shocks to geopolitical, trade and diplomatic norms, the most shocking thing of all may be the fact that the world economy has remained so steady in the face of such turmoil.

“Why is it that, despite all the uncertainty and all the turbulence, the world is performing so well?” asked International Monetary Fund (IMF) Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva during the Dilemmas around Growth session at Davos 2026. “Looking under the hood, we see four remarkable factors.

“One, the incredible agility and adaptability of the private sector. Two, the trade tensions we’ve experienced proved to be a lesser menace. We expected a big German Shepherd to bark, it turned out to be a sweet little poodle. Countries, especially in neighbourhoods, are strengthening their trade links. Tech-related trade has gone up.

“The third reason, enthusiasm about AI. Four, central banks and fiscal authorities have done a pretty decent job … supporting the economy when it needs support, trying to pull back when it is necessary to consolidate.”

Yet delving even deeper under the hood of the world economy reveals that while the engine is still running, certain parts of it are potentially being overworked.

These were the key economics takeaways from Davos 2026:

Thinking smartly about AI

AI’s promised productivity boom could inject fuel into global GDP, speakers in the Global Economic Outlook session agreed, and signs of advances are already materializing in many sectors.

“From a trade perspective, the work we’ve done shows AI could be very beneficial,” said World Trade Organization Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, citing reductions in trading costs, improvements in the way logistics are managed and a productivity bounce.

AI is also changing the nature of goods traded around the world, she said, with a shift towards technology-powered services. However, the potential AI offers comes with a clear warning.

“We forecast that AI would increase trade by 40% by 2040,” Okonjo-Iweala added, “but only if adoption is relatively equal. If not, we are going to create more inequalities... We have a demographic problem in those parts of the world where the innovation and the boom is happening. We shouldn’t forget the rest of the world. Emerging markets and poorer parts of the world are the markets of the future.”

Mohammed Al-Jadaan, Saudi Arabia’s Finance Minister, agreed: “We need to avoid underestimating the risks AI is going to bring, in terms of divergence of wealth. We need to ensure that AI Is diffused, and that the benefits go to as many people and as many small and medium-sized enterprises as possible. We need to be watchful.”

For Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, questions around AI’s impact must go beyond wealth to consider well-being. “We must be careful how we use AI so we don’t jeopardize social fabrics. From a public good point of view, how much [regulation] do we need? Do we want to facilitate this terrible path we have observed with the use of social media, with young kids prey to horrible behaviours?”

The impact on jobs, particularly at entry-level, also has to be not just considered but actively compensated for, according to Nela Richardson, Chief Economist at business outsourcing solutions provider ADP.

“Occupations that are exposed to AI have a vulnerability when it comes to early career,” she told the Chief Economists Briefing: What to Expect in 2026 session. “Think about what you did when you were 22. How many of the tasks you did then could be done by AI now? In every country, early career needs to be thought of intentionally by employers. As AI changes how we work and the ways we work, young people have to be brought along.”

For Georgieva, there is a clear way to do this. “We have to help people to enhance their skills and we have to make more opportunities for business to be created, including MSMEs, that demand these new skills.”

The promise of higher productivity

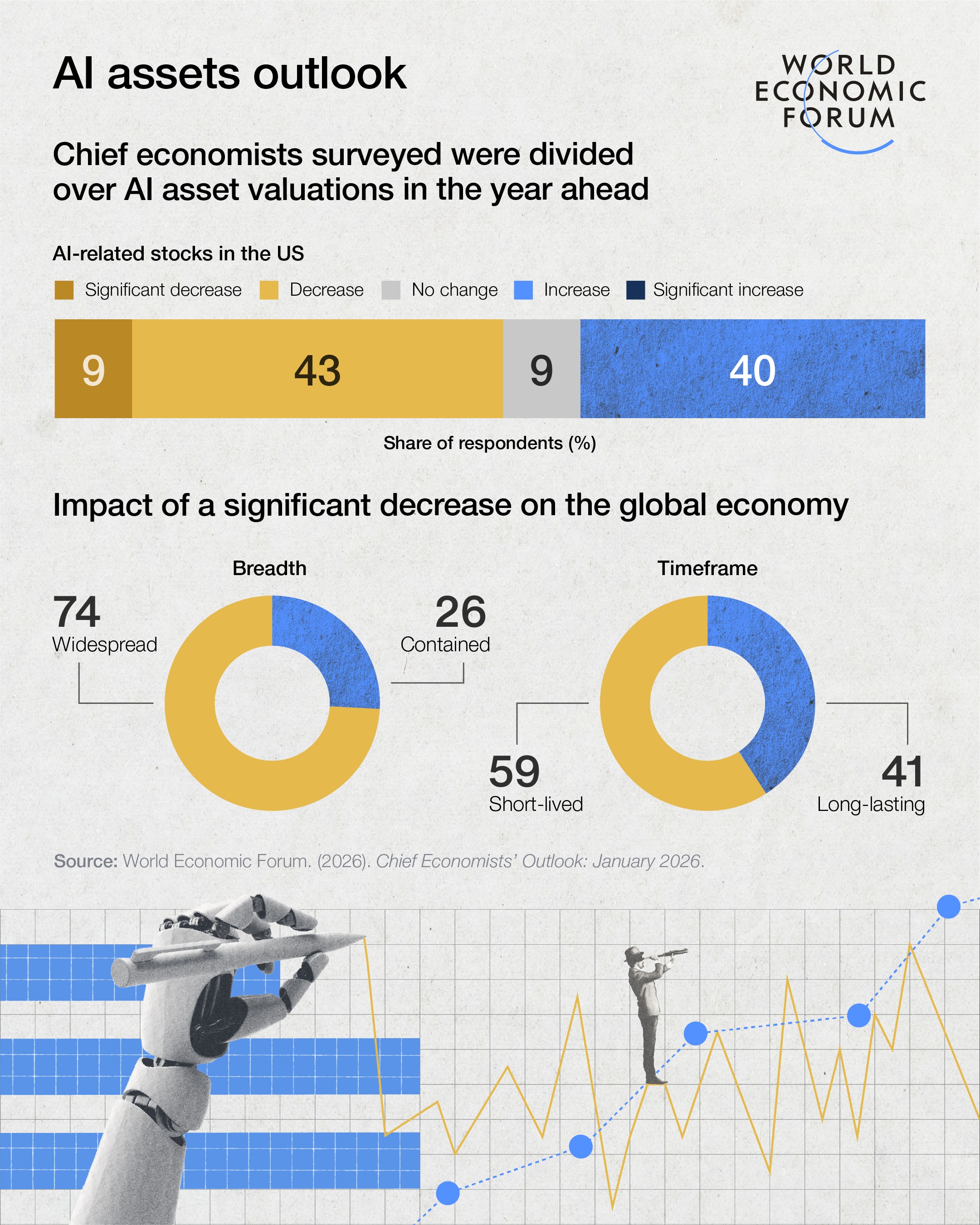

Is the much-mooted AI bubble about to burst?

“If the AI bubble bursts, it will be a key risk to the world, but it was seen as a key risk last year and it hasn’t materialised,” said Jianguang Shen, Vice-President and Chief Economist of Chinese e-commerce company JD.com in the Chief Economists Briefing: What to Expect in 2026 session.

For ADP's Richardson, one AI-related boom that is not a risk is the potential productivity increase it can create. “AI can deliver higher growth rates and solve the most challenging human conundrums on the planet,” she said. “But it’s going to take infrastructure that can keep up with the development, and right now we don’t have it.

Lagarde tapped into a similar theme, noting that AI needs the right conditions to thrive. “It is capital intensive, energy intensive, data intensive. It prospers if there is plenty of that. If we don’t work cooperatively, there will be less data to process, les capital flowing, and that is not conducive to the prosperity to a sector that is leading that game and is very promising to productivity.”

With slow productivity growth having held back economic growth over the past two decades, AI “is going to put transformation on steroids”, according to Georgieva. IMF research is also revealing knock-on effects in somewhat unexpected areas, she revealed:

“We did a micro-level study and found that, already in advanced economies, 1 in 10 jobs require new skills, so we have more people with higher skills. What happens there? They get better pay, they spend more money in the local economy, such as in restaurants, and demand for low-skilled jobs goes up. When we looked at the totality, we found for a 1% increase in higher-skilled workers, there is a 1.3% increase in total employment. AI is pushing more demand for low-skilled workers.

“The impact [of AI] on global growth could be somewhere between 0.1% and 0.8 %, and 0.8% is very significant. It would lift global growth above where it was during the pandemic.”

The 'other' debt

Another economic talking point that ran through Davos was debt, both in the public and the private sector

“AI developments are not primarily financed by debt at the moment,” pointed out Lagarde. “There is debt that is used to reform, restructure, invest in sustainable growth and which is conducive to productivity. That debt is healthy. Then there is the other debt.”

However, for Gilles Moëc, AXA Group Chief Economist, AI’s non-reliance on debt may not be the case for much longer. “The tech industry is moving from a situation where it was massively using retained earnings to pay for investments, to issuing debt,” he told the Chief Economists Briefing session. “I’m not saying this is unsustainable – their debt levels remain very low – but it adds to the need to fund a lot of new arrays of spending, in the private and public sectors. It’s an area we need to monitor in 2026.”

Richardson also pointed out that AI and the infrastructure it needs may not be able to rely on government support in the way other sectors have in the past. “You need people to build data centres, but you don’t need people to run data centres, so public support for resource-intensive builds like data centres may not be there in the way it was for factories going into a community.”

Tech investments are not just taking the form of AI forms building data centres. Companies in all sectors are having to spend to keep up with evolving tech needs, and the implications of taking out loans to fund large-scale investment are changing.

“We are dealing with an upward revision in the neutral long-term interest rate, when you think about the array of investment needs, combined with a level of savings that may start declining, depending on what ageing does to ageing patterns,” notes Moëc. “Will we be able to count forever on the kind of savings ratios we’ve had from elderly people in the last few decades? We have theories on that, but it’s never been tested.”

The prospect of higher interest rates can be punishing for those with high levels of debt, as Georgieva pointed out. “The [public] debt that is hanging on our necks, that is reaching 100% of GDP, is going to be a very heavy burden. It is tough for rich countries, devastating for poor countries when they have to pay more to service their debt than they pay for education and healthcare.

“We have seen doubling and tripling of borrowing costs. Fiscal consolidation has to be a priority. Restructuring debt has to be a priority. You are suffocating your public spending by having this big chunk of money that goes to interest rate servicing. Do you know what is going to knock on the door as demand for public policy support next week, next year? I don’t, but I do expect shocks to come. Shocks from geopolitics, technological advancement, climate shocks. I don’t know what it will be, but what I do know is we live in a world of more frequent exogenous shocks. A balanced budget is your tool to prepare and protect your people when the shock occurs.”

A world of shocks

The prospect of more regular shocks was picked up by several other panelists, including Okonjo-Iweala: “If I were a business leader or a policymaker, I would be planning for a world that is not going to go back to where it was, a world that will have built-in uncertainties, so I need to plan how to be resilient. If I was a country, I’d be trying to strengthen myself and my region.”

Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla, speaking in the Global Economic Outlook session, agreed: “In three to five years, the world will not be the same as it was, but clearly it will also not be the same as it is now. In several aspects, it will be better. I hope Europe will be more dynamic, more self-sufficient. I think China will emerge much faster. I think some things will be worse. I think the mistrust that has developed between nations… [is one of] the challenges we have to face.”

For Lagarde, this shifting situation means policymakers need to have “plans B”.

“We should not be talking about rupture, we should be talking about alternatives,” she said. “We should be identifying weaknesses. We depend on each other. We have very strong links and binds. All directions have to be explored.”

Okonjo-Iweala suggested these links and binds could in themselves be a potential weakness, if they come at the expense of other connections. “If business leaders and policymakers leave this place not knowing that they have to manage their dependencies, they’ve not taken away a lesson,” she said. “If we are overdependent on the US for markets on the trade front, overdependent on China for critical supplies – we need to diversify.”

For Saudi Arabia’s Al-Jadaan, the West also has a lesson to learn from the different – often more turbulent – circumstances and histories that other parts of the world have experienced. “My region has been living in a different world order for decades, and the West is now starting to experience it. Look at those who lived it for decades and how they had to deal with it. Singapore, Korea, China, the Gulf Cooperation Council. Build resilience and focus on what you can control.”

This message was echoed by Georgieva: “Our advice to our members: build strong fundamentals, build buffers, so when a shock hits, you can absorb it.”

Okonjo-Iweala meanwhile, called for “steady nerves”, saying “you don’t need to react to everything you see. You need to assess the situation. If you react immediately, you may react the wrong way.”

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.