Inside India's 'cancer capital' as it rethinks how care reaches patients

Deep dive

Image: World Economic Forum/Smita Sharma

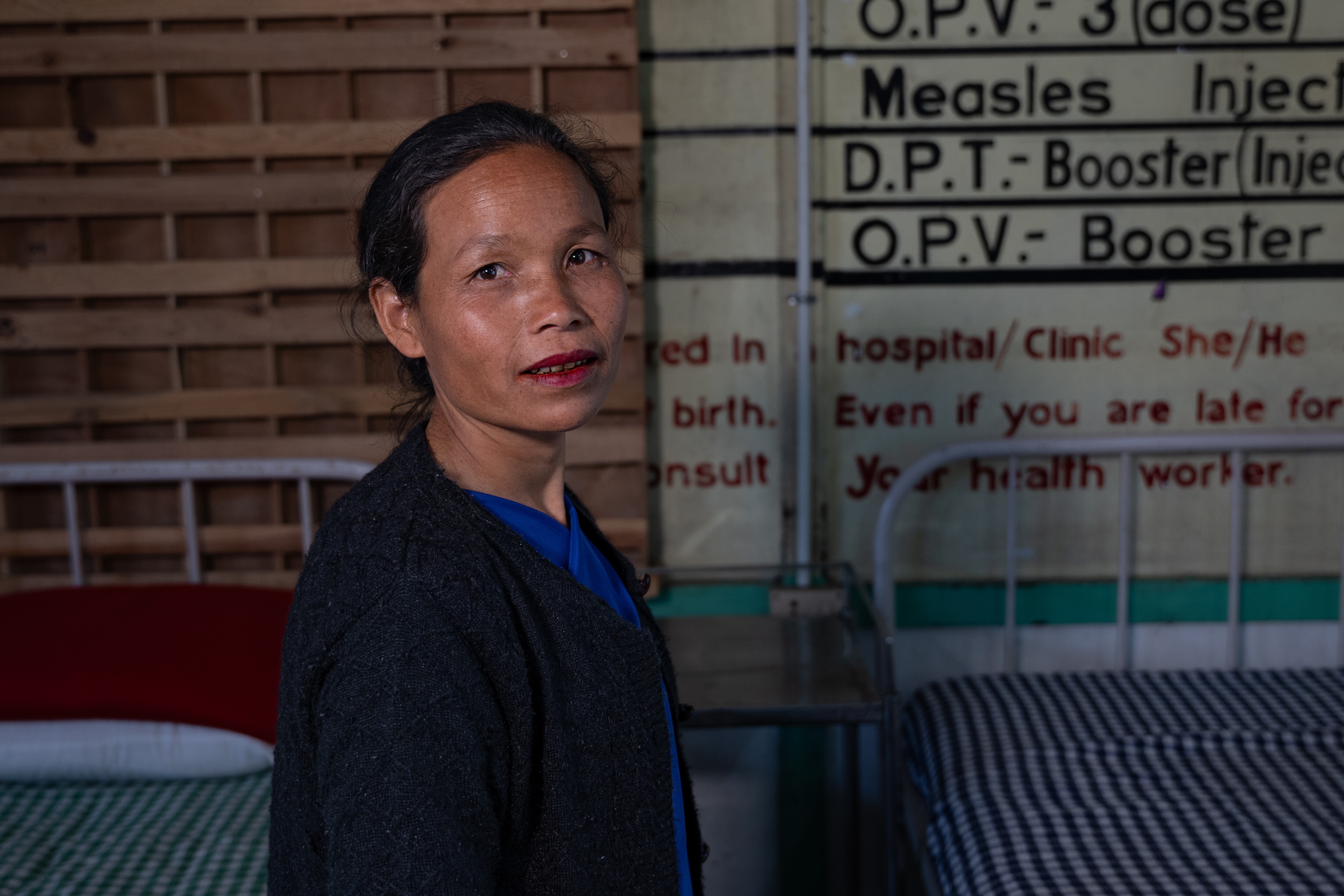

Shanti Mawlong thought it would be a routine visit to the doctor, not the day she might be confronting a cancer diagnosis.

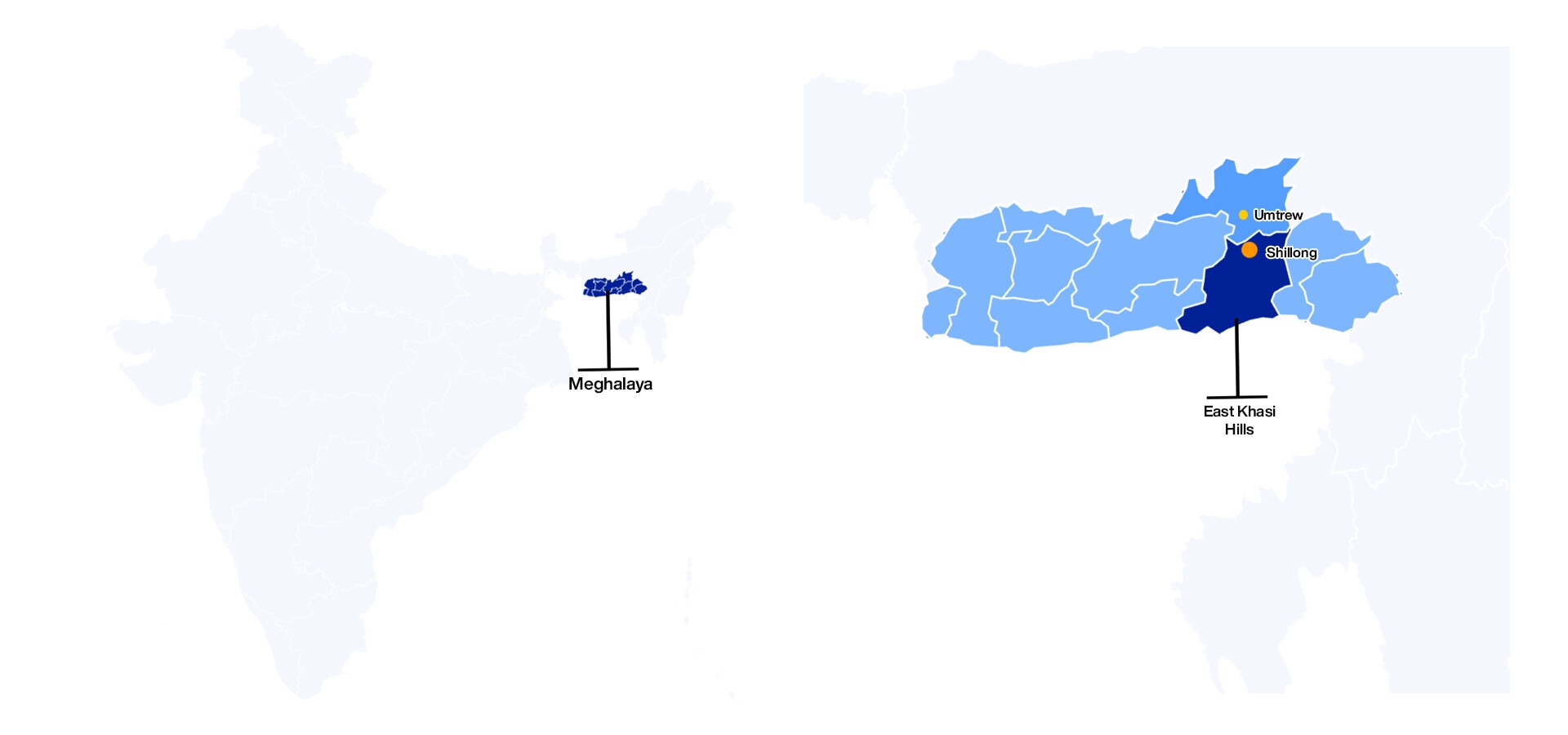

She boarded a shared cab from her village of Umtrew, paying ₹80 (about $0.90) for the 24-kilometre ride to Shillong, the capital of India's northeastern state of Meghalaya. As the cab climbed past foothills and roadside settlements, she mentally set aside her remaining ₹3,200 (or nearly $35) for any prescribed medicines, and for school supplies for her children.

The trip followed weeks of severe back pain. She initially visited a Community Health Centre (CHC) in a neighbouring village, where she says she was given a prescription for painkillers and calcium tablets, and then sent home without an examination or diagnosis.

But her symptoms began to worsen. She suspected her Copper-T might be the cause. The plastic intrauterine device (IUD), a T-shaped implant for birth control, had been in place for years and she wanted it removed. She turned to her village Sub-Centre, which is usually staffed by one female health worker. "The nurse, whom we all lovingly call Sister Majaw... initially asked me to come after a month," Shanti said. "But the pain was too much and I told her I couldn't wait." The next day, the nurse removed the IUD and gave her a referral note.

Two days later, the shared cab dropped her near a busy Shillong intersection. She paused for a modest meal, then walked to a private gynaecologist's clinic. Inside, the doctor examined her and performed a biopsy.

Pending the result, the doctor said it could be cancer. "I broke down right there in her clinic," Shanti said. "But the doctor didn't charge me for the consultation or medicines. She only asked for ₹3,000 for the biopsy, which actually costs more."

"I left with just ₹200 and used that to get home. The crying and sadness just continued."

The rising cancer burden

Globally, the burden of cancer is growing.

According to estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the World Health Organization (WHO)'s cancer agency, the number of new cancer cases is expected to exceed 33 million by 2050 — a 65% increase over 2022 figures.

India sits at the centre of that shift. With its large population and changing disease patterns, the country is expected to see a 90% rise in cancer cases over the same 2022-to-2050 period, reaching close to 2.7 million diagnoses annually — the third-highest number in the world, after China (7.31 million) and the United States (3.51 million).

While wealthier countries have seen improved survival rates after decades of incremental advances in screening, surgery and drugs, uneven progress in low- and middle-income countries is expected to drive higher mortality. In India alone, annual cancer deaths could nearly double by 2050, from under one million to about 1.83 million.

Experts from across India's cancer ecosystem — clinicians, public health specialists, researchers, civil society, and healthcare companies — have pointed to six structural gaps: weak data systems, delayed diagnosis, limited skills and training at the frontlines, high out-of-pocket costs, fragmented patient journeys, and a severe shortage of trained specialists.

These are national patterns but they are felt most acutely in places like Meghalaya — a state with a high disease burden, difficult terrain, limited specialist capacity and deep rural–urban divides in access to care. It has also carried a reputation of being the 'cancer capital of India' for its unusually high cancer rates.

It was in East Khasi Hills, the state's most populous and cancer-affected district, that Meghalaya attempted to respond through a pilot called Megh CAN Care. And it was here, amid these efforts, that Shanti confronted her diagnosis of Stage 2 cervical cancer.

Some people suggested she try traditional medicine, while others offered words of hope. One doctor suggested she consider travelling thousands of kilometres south to Tamil Nadu for treatment, if her finances allowed.

She eventually received care at Shillong's Civil Hospital, the state's main dedicated public cancer facility, and survived. But the experience left behind lingering debt and a sharp awareness of how unprepared she had been for what followed.

Her story echoes across the district.

To understand what it looks like when cancer policy meets everyday life and systems may hold or falter, we reported across East Khasi Hills (and beyond), speaking with patients, doctors, health workers and officials. What emerged was a picture not of a single broken system, but of many overlapping realities.

Some begin long before illness, shaped by daily habits and exposure. Others are shaped by belief — in faith, in healers, or in silence. Then there are realities of access, where care exists on paper but not in practice; of cost, which quietly determines who continues and who drops out; of technology, often impressive in pilots but thinly embedded in routine care; and of governance, which carries ambition unevenly across time and terrain.

We begin with the quietest reality, which builds over the years — risk.

Risk

In a world where tobacco use is declining, Meghalaya's landscape tells a different story.

Step into any home or gathering here and chances are you'll be offered kwai, a small bundle of sliced areca nut wrapped in betel leaf, typically mixed with slaked lime and often, tobacco. It's sold for ₹10 (about $0.12) and stocked in nearly every local shop.

For generations, kwai plantations are said to have sustained families across the state. But consumption has expanded into daily life: people chew while walking and working, in conversation, during rituals — even at wakes and births.

Official survey data suggests nearly half of Meghalaya's adult population uses tobacco in smoked or smokeless form, well above the national average of 29%. Prevalence is higher among men, with one-third consuming alcohol. Among women, smokeless forms dominate, often alongside kwai.

And for many, the habit begins early. "Most tobacco users here start between the ages of 11 and 14," said Ramkumar S, Secretary of Meghalaya's Health and Welfare Department. "And peer pressure plays a big role."

Over time, the damage becomes visible. Meghalaya reports disproportionately high rates of oral and oesophageal cancers, diseases closely associated with long-term use of tobacco and areca nut. Health officials say it's not just a matter of individual choices but of deeply embedded social norms, which health systems are only beginning to confront at scale.

On the frontlines of prevention are community health workers known as Accredited Social Health Activists, or ASHAs. Long described as the "backbone of India's healthcare system," these local women typically work at the village or neighbourhood level, with a primary focus on maternal and child health. But as chronic illnesses rise, many are now being trained and modestly incentivised to support screening, prevention and awareness for non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Ailis Mary Talang, one such ASHA worker in Meghalaya, has been conducting door-to-door campaigns for nearly two decades. She has also been trained to raise awareness around hypertension, diabetes and tobacco use.

Sitting at a local public health centre in Shillong, she described the limits of that work. "When we come across people smoking and chewing tobacco, we educate them," she said. "But when it comes to a person diagnosed with cancer, they often do not share this information with us; we usually find out from the neighbour next door."

She was also candid about her own habit. Ailis chews 30 to 40 pieces of kwai a day - her teeth are stained a deep red. "I don't have an answer to why I like eating kwai," she said. "Before I would eat just a few but gradually I became addicted to it."

She knows the risks and shares them with others. But her addiction, like many in the state, is both personal and generational. "I'm scared but I can't help it. Our grandparents also chewed kwai... my grandmother lived to be 90 but didn't have cancer."

The contradiction she carries - of awareness alongside continued use - is far from uncommon. Even survivors don't always change their behaviour immediately.

Ikram Ali, who beat cancer twice, put it bluntly: "I became truly human only after I fell sick. I used to smoke two to three packs of cigarettes daily. I drank two to three times a day… I knew it was wrong. I had all this knowledge."

His experience mirrors what state officials say they are trying to prevent. "Tobacco is not just a health issue," Ramkumar said. "It's a gateway to other addictions. We're trying to intervene early."

The efforts, he said, have shifted away from hospitals alone. Programmes such as Tobacco-Free Educational Institutions (ToFEI) and the state's Tobacco-Free Villages initiative aim to decentralise prevention by training teachers as anti-tobacco champions, mobilising village health councils and enforcing restrictions on tobacco sales near schools and public spaces.

"I wouldn't say that others can immediately learn from us because we need to show results,” Ramkumar said, after Meghalaya received recognition from the World Health Organization in 2023. "The results will come up in the next surveys. But we must continue to decentralise prevention using schools and community spaces, not just hospitals."

In Meghalaya, the risk is visible, habitual and socially reinforced. And changing it, health officials say, will require time, trust and the slow work of shifting norms that have shaped everyday life for generations.

Belief

Beyond risk factors, what people believe — and fear — is shaping cancer care in Meghalaya just as powerfully.

For Homstar Dohtdong, it changed the course of treatment.

He first noticed a burning sensation behind his throat, which was manageable but uncomfortable. After tests, he was diagnosed with a cancer of the hypopharynx, which is highly prevalent in the region, and was advised to start chemotherapy. That was when fear set in. "I was scared of the side effects and decided to opt for traditional medicine."

Encouraged by friends and family, Dohtdong moved from healer to healer across different villages over the next year, carrying his medical reports with him. One said it was gastritis. Another said it was poison. One acknowledged it was cancer, but told him it could be healed slowly with traditional remedies.

The medicines came as powders, liquids, and what he described as "pieces of wood" to boil at home. They brought short relief, he said, but never a cure. Still, they felt safer than injections, drips or surgery. "With traditional medicine, you just drink it," he said. "No injections or anything. That gives you more courage to opt for traditional medicine."

At Shillong's Civil Hospital, Dr Anisha Mawlong, one of the state's few oncologists, sees this fear play out repeatedly. "Cancer treatment is different from other illnesses," she said. "If you have a gallbladder stone, you remove it and you're fine. If you have a cyst, you take it out and you're fine. But cancer treatment itself causes pain. Chemotherapy will pull you down before it makes you better. There are side effects, and that fear keeps people away."

Radiation, she said, carries its own stigma. "In the local dialect, it's sang — it means burned. So nobody agrees to radiation." Things are changing, but slowly. "People are seeing others survive, overcome side effects and come back stronger. But the fear is still very real."

That fear, she added, is often amplified at home. "Most of the time, it's the relatives who are the stumbling blocks. Someone will tell them, 'Don't do this, my neighbour did radiation and died.' And then if the patients refuse, we can't force them. They leave and sometimes come back only when it's terminal."

For Dohtdong, the symptoms eventually worsened and he began losing weight. At times, he coughed blood. "That's when I decided on my own to come back," he said.

This time, the 45-year-old stayed, completing treatment and slowly regaining strength. Sitting inside Dr Mawlong's examination room in Shillong, his voice still hoarse from radiation, he reflected on the journey.

"I firstly want to thank God that I am here today," he said. "Before, I was so thin, only bones. Now, the swelling has gone. I feel much better."

Faith runs alongside fear in Meghalaya, where nearly 75% of the population is Christian and three major tribes dominate the landscape: the Garo in the Garo Hills, the Khasi in the East and West Khasi Hills, and the Jaintia in the Jaintia Hills.

For some, it becomes a bridge back to care. For others, it deepens hesitation. Church leaders interviewed for this story said they have seen both — sometimes in tension, often in tandem. "Some of the misconceptions surrounding cancer are that 'God has given us this, so we don't need to do anything with it. Let's believe in God," one church leader said. "And I'm not saying we shouldn't believe in Him. We have to believe in Him, pray to Him, but at the same time seek help."

Another said churches increasingly encourage early medical care and run awareness programmes across health centres. "We know that God can heal you," he said, "but at the same time, we always tell people to go and seek medical help."

But silence remains common and cancer is still spoken about in whispers or in retrospect. Health workers say people rarely report symptoms early, and patients who do reach public hospitals often ask few questions during initial consultations. Dohtdong himself admits he had very little understanding of cancer when he was first diagnosed.

Without counselling, fear fills the gaps left by limited information — shaping decisions, delaying care and complicating every step that follows.

Access

For patients who do come forward, geography becomes part of the treatment plan.

Meghalaya has a population of 4 million, comparable to Los Angeles, spread across nearly 7,000 villages and just over 20 urban centres, many of them nestled deep in the hills.

Against this backdrop, the state is trying to provide public healthcare across different tiers. For the majority living in rural areas, initial advice is available from village health councils and the voluntary ASHA workers. Basic screenings and immunisations are carried out at a sub-centre that serves eight to ten neighbouring villages.

If the ailment requires overnight treatment, a Primary Health Centre (PHC) with around 10 beds serves a population of roughly 20,000 to 30,000. Patients can then be referred upward to a Community Health Centre (CHC) for minor surgeries and more complex care. District-level hospitals sit at the top of this public system, offering specialised treatment for larger catchment areas.

In theory, this tiered system is meant to ensure coverage. In practice, it often translates into longer journeys, higher costs and delayed diagnosis, as some locals have found. "This is the biggest problem in India," said Ikram Ali. "The cancer isn't diagnosed on time and when it is diagnosed, the treatment doesn't come easily."

Ikram spent three months navigating the system, visiting various doctors and taking medications for a range of suspected conditions, including a throat infection. "They didn't perform any tests for cancer." Eventually, he travelled to Guwahati, in neighbouring Assam. "Back in 2017, there weren't many medical facilities here, in Shillong."

"Most of the care has been concentrated in the urban population," said Dr P. Jagannath, Chairman of Surgical Oncology at Mumbai's Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, who helped shape the technology blueprint of the whitepaper that informed the Meghalaya pilot. "If we can get access to care to a remote northeast state, we can literally solve the problem in any other state or any other population in the country."

Another survivor, Elistina Palei, encountered a similar gap. After being diagnosed with breast cancer in Shillong, she was referred outside the state for a PET scan, which is a basic but crucial step in staging cancer.

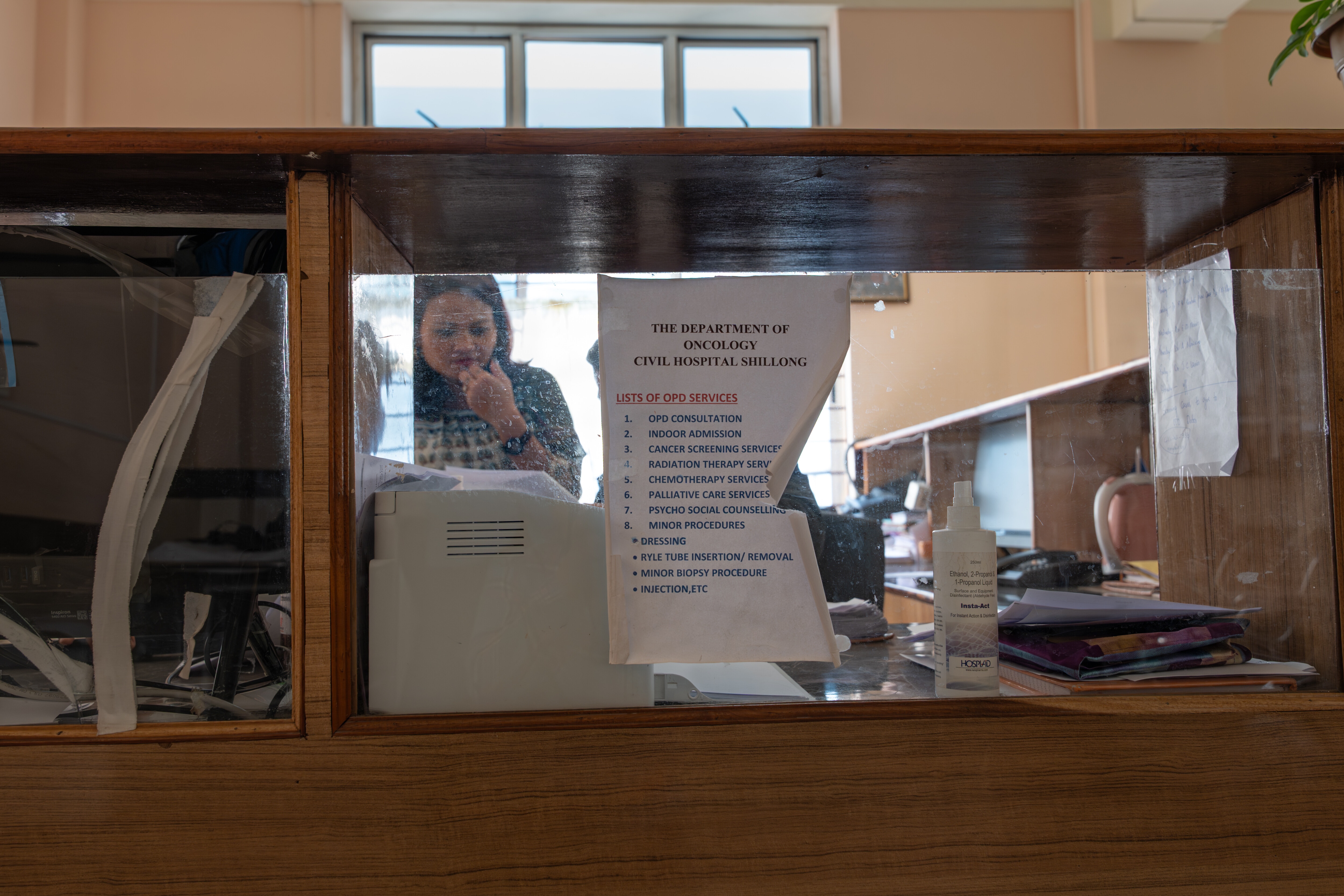

Even now, radiation oncologist Dr Anisha Mawlong said, "We have to send the patient all the way to Guwahati for a PET scan." The journey is nearly 100 kilometres from the capital. The cancer ward she oversees at the Civil Hospital in Shillong has just 90 cancer beds and a handful of oncologists.

"We are four doctors handling the entire oncology burden - not just radiation. We also handle chemotherapy, palliative care, screening and awareness. Our basket is full."

She wishes for more, not just in terms of headcount but expertise. "We need medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, a dedicated palliative care team and a separate team for preventive oncology. Right now, all of that falls on the same few of us."

The absence of multidisciplinary teams has consequences. As one health official explained, "Should we give chemotherapy first or radiotherapy? Should we operate at all, or give only radiotherapy? Those discussions are missing here." As a result, many patients end up receiving radiation by default.

Such gaps are not unique to Meghalaya. The first Lancet Oncology Commission found that only 25% of cancer patients worldwide had access to safe, affordable and timely surgery. It's a deficit that is even more pronounced in low- and middle-income countries.

NEIGRIHMS, a centrally run tertiary institute in Shillong, offers specialised care across the Northeast but it was never designed to meet the everyday staffing needs of Meghalaya's own public health system. The state admits the system is far from complete: "Once you identify someone with cancer, the real challenge begins," said Ramkumar S, Secretary of Health. "Where do they go? How do you treat them? It's a long journey."

"The rural-urban divide in healthcare is also very real, not just in Meghalaya but across the world," he added. "We can't fix it overnight."

At the core of the problem, Ramkumar said, is the shortage of health professionals in rural areas. While demand for specialised care is high, most doctors come from urban backgrounds and have little connection to rural communities. "They do not come from rural areas, and they do not have a connection with rural areas," he said, linking the gap back to unequal access to education and how that, in turn, shapes access to healthcare.

That divide is what the state's first government-run medical college, which recently welcomed its first batch of students, hopes to bridge by training more local doctors and anchoring talent within the state.

Part of the solution also lies in task shifting, Ramkumar said, which involves training general physicians and nurses to perform initial cancer screening and imaging so it reduces the load on oncologists.

In the longer term, officials also see a need to build specialist capacity from within. One option, said a health official, is for the state to sponsor advanced training seats in oncology. "Seven or eight years down the line, those doctors could return and start training others."

"That has to be the long-term vision."

Finance

In Meghalaya, reaching care after crossing barriers of access does not guarantee that treatment can be completed.

In East Khasi Hills, clinicians and patients say doctors often avoid directly naming cancer — or jingpang bampong, as many locals describe it. The term translates loosely to an internal sickness that keeps growing. Once spoken, it can trigger anxiety about suffering and, just as urgently, the cost of treatment.

Melinda Kharshandi is familiar with that tension.

Between her daily chores, her role as support staff at the local health department, her church visits and the occasional fishing trip, she had been feeling unwell for months. She was treated for gastritis before her symptoms worsened — a loss of appetite, unexplained weight loss and nausea that eventually pushed her to Shillong.

A gastroenterologist there advised hospitalisation without specifying the cause. "I didn't care to ask because the sickness had taken a toll on me and I just wanted some relief from it," she said. It was only after she was referred to oncologist Dr Anisha Mawlong that she learned she had oesophageal cancer. "I was told I would have to undergo chemotherapy and I understood… I wasn't scared at all. I don't understand why people are so afraid of cancer."

Melinda had been a heavy user of tobacco and kwai, and her diagnosis didn't surprise her. But with no savings and a family that relied on her income, treatment felt like an impossible decision. "Initially, I was planning to refuse," she said. "I didn't want to leave my family in debt if I didn't survive."

Melinda eventually began chemotherapy after borrowing money from friends and family. As a government employee, she later received reimbursement for the expenses she had initially paid out of pocket.

But the journey to recovery stretched over four years and left lasting effects. In order to keep her job while she was unwell, Melinda's daughter dropped out of 12th grade and never returned to finish her education. "I felt bad for her," Melinda said. "I encouraged her to go back to school, but she told me she couldn't concentrate after such a long break."

"Without money, especially when you're ill, it becomes very challenging."

Her experience is echoed by many patients across the state. While Meghalaya's public health insurance scheme, the Megha Health Insurance Scheme (MHIS), covers hospitalisation and cancer treatment up to ₹5.3 lakh (about $5'875) per family annually, it doesn't cover everything. Patients still pay out-of-pocket for transportation, diagnostic scans, food, lost income and post-treatment care. Reimbursement is common but only after expenses are covered upfront.

For households already living close to the margin, that gap can force hard choices: sell land or delay treatment, cut expenses or pull children from school, borrow money or go without care.

These pressures also play out differently depending on where one stands in the system. For patients, it can mean choosing between attending chemotherapy and earning a day's wage. For frontline workers like ASHAs, categorised as volunteers and paid a fixed monthly incentive of around ₹3,000 (or $33), this can mean prioritising maternal and child health work, which carries additional incentives, over cancer awareness, which does not.

"We do follow up on cancer cases," said one ASHA. "But it's not a regular part of our work. We're not paid for it."

For the state, the challenge is structural. "A state like Assam has opened more than ten cancer hospitals with help from a foundation," said a senior state official. "But that model isn't easy for every state. Infrastructure is expensive. It's a challenge."

Meghalaya now allocates eight per cent of its total state budget to health, one of the highest shares among Indian states, yet its per capita income remains among the lowest. Most households rely on agriculture, informal labour or small-scale trading, with few buffers when illness strikes. "People in rural areas do prioritise health," said Ramkumar. "Because when they lose health, they lose everything — their livelihood, their stability. But access, affordability and awareness still haven't caught up."

Inside hospitals, clinicians often find themselves adapting care around these financial constraints. "Once a patient is diagnosed with cancer, or even when something suspicious comes up, we always try to admit them," said Dr Anisha Mawlong. "As an outpatient, there are fewer options for free facilities, right from diagnostics to treatment. But as an indoor patient, you get everything free."

Many patients, she added, never fully grasp the scale of that support. "They don't realise how much treatment and diagnostics they are getting for free."

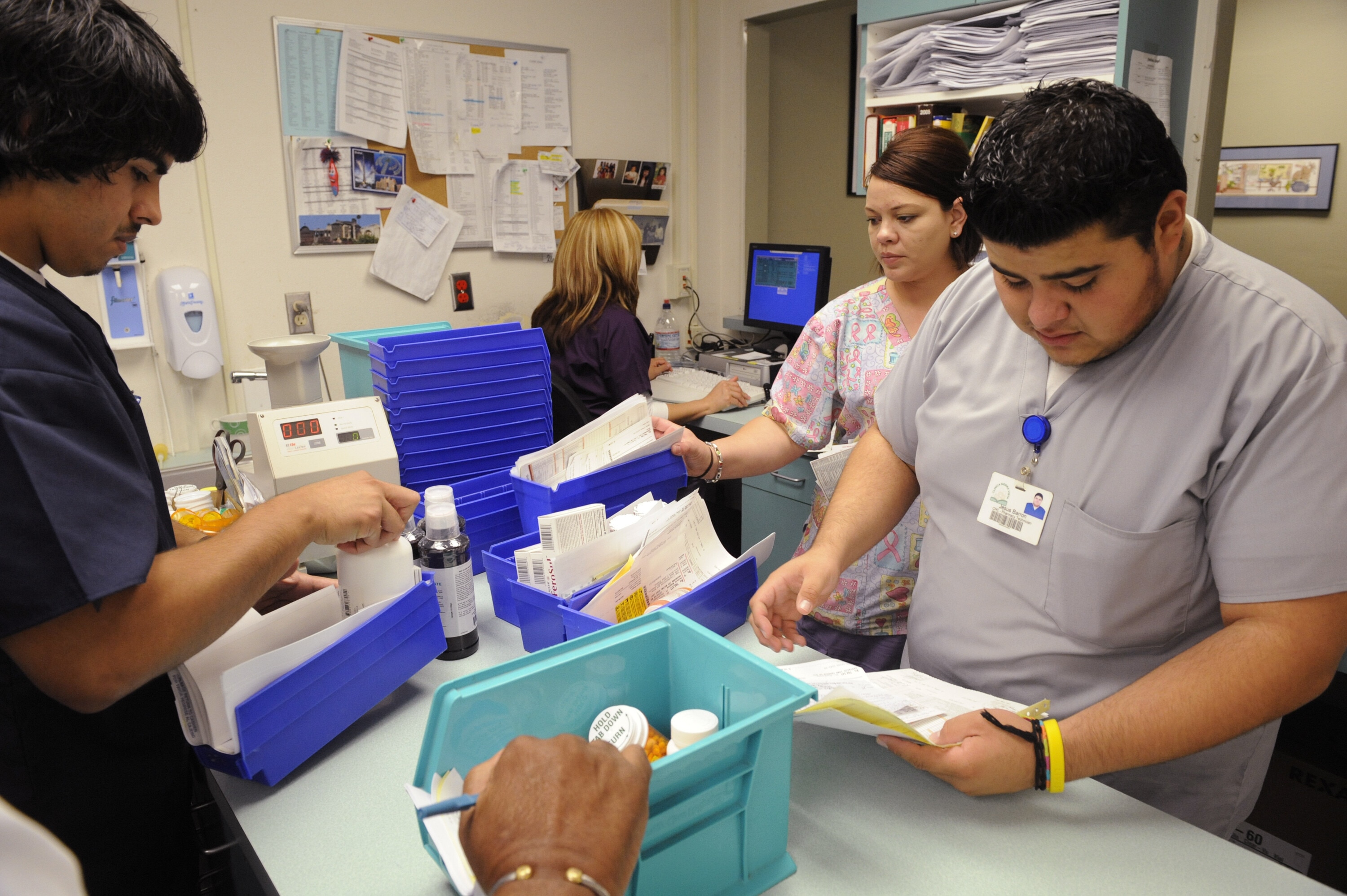

Innovation

In underserved regions like Meghalaya, innovation is shaped less by ambition than by constraint. Health officials and clinicians say technology matters for its ability to stretch limited systems: reaching patients earlier, supporting overstretched staff and compensating for the absence of specialists.

That logic shaped the Megh CAN Care pilot. A small number of portable screening devices were deployed at primary and community health centres to bring services closer to where people live. Among them was the AI-enabled EVA mobile colposcope for cervical screening — a tool that studies suggest is good at picking up potential disease, but less reliable at ruling it out. In practice, that makes it unsuitable for definitive diagnosis but nonetheless helpful as a triage aid in places like Meghalaya, where specialist care is limited.

The level of accuracy displayed by AI systems continues to evolve, as Ram Kumar said. "It carries potential but it isn't there yet."

Other technologies are being explored for different pressure points in the system. Virtual reality, for instance, is being tested to address skills gaps and patient anxiety in palliative care. "If someone is diagnosed with cancer and needs convincing in terms of undergoing treatment, VR will help explain how it works," said Sampath Kumar, Principal Secretary of Health and Family Welfare in Meghalaya. "How chemotherapy, for instance, works inside your body to kill cancer cells."

"It helps remove some of the fear and anxiety around the process, while easing pain for others," he added, particularly in settings where specialist counselling is limited.

In parallel, a focus on telemedicine is growing. "In 2021, we were doing 150 tele-consultations in the whole year," said Ram Kumar. "Now we're doing 600 a day." With more than half of Meghalaya's villages located over 30 minutes from the nearest primary health centre, officials see digital consultations as one way to reduce the burden of distance.

Yet many health professionals argue that none of these tools will truly change outcomes without something more basic: shared, digitised health records.

"So a doctor in Shillong can understand the symptoms being exhibited by a patient at a small sub-centre, hundreds of kilometres away," said one official. "Or determine whether a follow-up was done and if not, dispatch an ASHA worker to the patient's address. These records need to be made and centralised."

The Forum's white paper on cancer care echoes that view, arguing that better outcomes depend not just on new tools, but on shared data systems that can follow patients across facilities and over time — and on a common language to make that possible. "Today, while the FHIR standard is available internationally for health and digital health, we felt the need for an oncology-specific language," said J. Satyanarayana, a core author of the whitepaper. "An oncology-specific schema has been developed in alignment with the FHIR standard. This will be useful not only for India, but for the whole world."

But, he cautioned, "a standard is only as strong as the number of institutions that adopt it. So we need to popularise it."

In Meghalaya, that vision was tested following the Megh CAN Care pilot. An Oncology Data Model was developed with support from a national technical agency, focusing on the pilot's most immediate priorities: screening and risk assessment. According to project documents, it standardised how this early-stage data could be captured and shared, but stopped short of covering the full complexity of cancer care.

The architecture was deliberately left open-ended, designed to be expanded over time to include diagnostics, specialised procedures and even genomic data.

For now, it represents an attempt to move beyond unorganized paper trails and establish a pragmatic first layer of infrastructure. But without broader adoption and deeper data integration, its 'game-changing' potential remains theoretical.

Governance

By 2022, cancer had become a governance problem Meghalaya could no longer treat as peripheral. "Cancer-related issues came up as one of the top three causes of mortality in the state, especially for men," said Ramkumar S.

In response, the state designed a pilot called Megh Can Care, in partnership with the Apollo Telemedicine Networking Foundation (ATNF). The pilot focused on East Khasi Hills and its estimated 350,000 residents over the age of 30.

"The three broad objectives for the pilot were: to build capacity in our health systems for screening," Ramkumar said. "Number two is to screen everyone over 30 years of age at scale, especially at the rural level, for five types of cancer — breast, lung, cervical, oral and oesophageal. And the third objective is to use technology for both screening as well as capturing the whole process of the continuum of care."

For Apollo, the intent was to develop a public–private model that could extend beyond a single geography. "Population health is a shared responsibility of both government—at the Union and State levels—and the private sector," said Sangita Reddy, the Joint Managing Director at Apollo Hospitals Group. "This is especially pivotal in advancing non-communicable disease control, particularly cancer, in India."

"Through collective action and cross-sectoral partnerships," she added, "we can promote awareness, encourage early engagement, ensure quality screening and treatment, and build a stronger, technology-enabled and responsive health system."

Reaching people at that scale meant going far beyond clinics — across hills, villages and informal settlements. Awareness campaigns were carried into communities through local media, social media influencers, elected village health councils and faith institutions.

"The advice was coming from the local health council," said Sampath Kumar, Principal Secretary of Health and Family Welfare, "because that will have a better impact than someone coming from our side." He pointed to the scale of that effort: "Almost like 7,000 village health councils are there in the state now."

"We have also done screening camps in churches, in schools and colleges, in health centres — so we have done campaigns wherever people feel most comfortable," said Ramkumar.

Over 18 months, 104,387 people were screened to assess their cancer risk, with about 44% screened in rural blocks. For the state, the numbers reflected both reach and constraint. "If someone walks up to your door and tells you, 'I need to screen you for five types of cancer,' we need to consider whether people will be ready for it," Ramkumar said. "It takes a bit of a scientific temper to understand that I should get screening done now before it causes me pain."

Experts involved in the white paper that informed the pilot say this hesitation is not unusual. Screening, they argue, tends to work best only after people recognise symptoms as something that requires care. "The first step is to build awareness," said Dr Jagannath. “If a woman knows that a lump in the breast needs to be checked, she will come on her own. That makes a big difference."

Those flagged as at risk during the pilot were referred onward, but follow-through proved uneven. According to project data, around 2,000 people visited a higher health facility, while more declined referral. Among those who did follow up, 11 cancers were confirmed during the pilot period.

For clinicians, the exercise highlighted limitations. "It was more of a questionnaire-based screening, not a physical screening or a device-based screening," said Dr Anisha Mawlong. "That is what we will be learning from."

Device-based screening was used more selectively. Project records show that 988 screenings were conducted using portable devices for breast and cervical cancer.

As awareness increased, pressure on the system became visible. "If you go and see our cancer hospital, it's full," said Sampath Kumar. "There are beds even in the corridors now." The state, he said, is responding by expanding capacity. "Every district now has the capacity to diagnose oral cancer and oesophageal cancer. We have set up endoscopy machines everywhere."

For Ramkumar, the pilot was never meant to stand alone. "This MeghCan Care programme was designed in such a way that it can be replicated with the public health systems," he said. "That replication is very important because we do not want to do it as a one-time affair."

Since the pilot, the state has increased funding to the State Cancer Society and has begun carrying out the work independently. But officials are clear that screening alone cannot carry the burden. "Every state budget has a part of money which is going for prevention and promotion, but it is a very small amount compared to the curative care which we generally do," Ramkumar said. "This is the situation that plays out across the world."

Beyond the pilot

Shanti Mawlong sits calmly in her home in Umtrew, her hands folded in her lap. It has been more than a year since her last cancer check-up.

She remembers the months around her diagnosis in practical details: the trips back and forth to Shillong, the money she had to arrange, the uncertainty of what would happen next. And how she kept faith close during her hospital stay. "Apart from the Bible, I kept a book containing God's words very close to me," she said.

She remains grateful for the doctors who treated her, for the people who helped her through it, and for the fact that she survived. But the experience still lingers. "When I was diagnosed, I had no idea what to do or where to go," she said. "There should be counselling… someone to explain the steps and treatment options."

That gap — between identifying risk and finding a clear path through care — surfaced repeatedly across East Khasi Hills. Many clinicians stressed that awareness remains the first hinge. But awareness alone, they warned, is not enough. Once people come forward, the system has to be ready for what follows: diagnosis, referral, treatment, follow-up and the long stretch after care ends.

Meghalaya's experience reflects a wider challenge across low- and middle-income settings, where pilots can open doors and technology can help extend scarce expertise. But without systems that can absorb demand and sustain care over time, these efforts remain fragile.

That is where the state remains central. Continuity depends on public financing that outlasts project cycles, on data systems that sit inside public health architecture, and on accountability that doesn't end when a pilot does.

None of this lends itself to quick wins. Cancer unfolds over years, often decades, crossing institutions and geographies along the way.

Meanwhile, Meghalaya continues the work by expanding diagnostics, pushing prevention deeper into villages, churches and schools, and slowly building capacity within the system.

It doesn't guarantee outcomes but it signals a shift away from seeing cancer as a campaign, towards treating it as a long responsibility: one that requires staying, correcting course and showing up long after the screening camp has packed up and left.

Additional reporting by: Pratyush Sharma, Lead, Digital Health, World Economic Forum; Princess Giri Rashir, a Shillong-based journalist and Ritwika Mitra, an independent journalist.

Visuals by Smita Sharma. Additional support from Md Meharban.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Sylvia Varela

February 4, 2026