This is why time seems to go by more quickly as we get older

There are several theories which attempt to explain why our perception of time speeds upas we get older. Image: REUTERS/Jo Yong-Hak

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

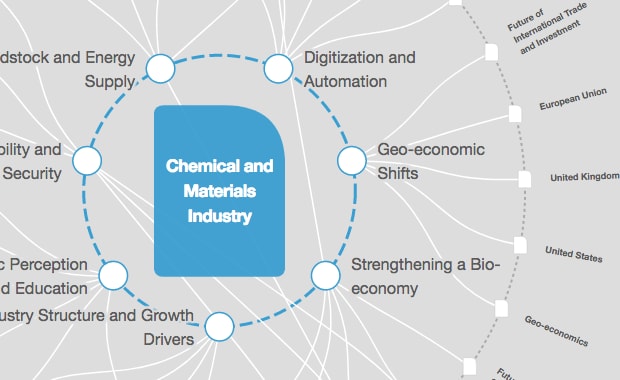

Chemical and Advanced Materials

When we were children, the summer holidays seemed to last forever, and the wait between Christmases felt like an eternity. So why is that when we get older, the time just seems to zip by, with weeks, months and entire seasons disappearing from a blurred calendar at dizzying speed?

This apparently accelerated time travel is not a result of filling our adult lives with grown-up responsibilities and worries. Research does in fact seem to show that perceived time moves more quickly for older people making our lives feel busy and rushed.

There are several theories which attempt to explain why our perception of time speeds upas we get older. One idea is a gradual alteration of our internal biological clocks. The slowing of our metabolism as we get older matches the slowing of our heartbeat and our breathing. Children’s biological pacemakers beat more quickly, meaning that they experience more biological markers (heartbeats, breaths) in a fixed period of time, making it feel like more time has passed.

Another theory suggests that the passage of time we perceive is related to the amount of new perceptual information we absorb. With lots of new stimuli our brains take longer to process the information so that the period of time feels longer. This would help to explain the “slow motion perception” often reported in the moments before an accident. The unfamiliar circumstances mean there is so much new information to take in.

In fact, it may be that when faced with new situations our brains record more richly detailed memories, so that it is our recollection of the event that appears slower rather than the event itself. This has been shown to be the case experimentally for subjects experiencing free fall.

But how does this explain the continuing shortening of perceived time as we age? The theory goes that the older we get, the more familiar we become with our surroundings. We don’t notice the detailed environments of our homes and workplaces. For children, however, the world is an often unfamiliar place filled with new experiences to engage with. This means children must dedicate significantly more brain power re-configuring their mental ideas of the outside world. The theory suggests that this appears to make time run more slowly for children than for adults stuck in a routine.

So the more familiar we become with the day-to-day experiences of life, the faster time seems to run, and generally, this familiarity increases with age. The biochemical mechanism behind this theory has been suggested to be the release of the neurotransmitter dopamineupon the perception of novel stimuli helping us to learn to measure time. Beyond the age of 20 and continuing into old age, dopamine levels drop making time appear to run faster.

But neither of these theories seem to tie in precisely with the almost mathematical and continual rate of acceleration of time.

The apparent reduction of the length of a fixed period as we age suggests a “logarithmic scale” to time. Logarithmic scales are used instead of traditional linear scales when measuring earthquakes or sound. Because the quantities we measure can vary to such huge degrees, we need a wider ranging measurement scale to really make sense of what is happening. The same is true of time.

On the logarithmic Richter Scale (for earthquakes) an increase from a magnitude ten to 11 doesn’t correspond to an increase in ground movement of 10% as it would do in a linear scale. Each increment on the Richter scale corresponds to a ten-fold increase in movement.

But why should our perception of time also follow a logarithmic scaling? The idea is that we perceive a period of time as the proportion of time we have already lived through. To a two-year-old, a year is half of their life, which is why it seems such an extraordinary long period of time to wait between birthdays when you are young.

To a ten-year-old, a year is only 10% of their life, (making for a slightly more tolerable wait), and to a 20-year-old it is only 5%. On the logarithmic scale, for a 20-year-old to experience the same proportional increase in age that a two-year-old experiences between birthdays, they would have to wait until they turned 30. Given this view point it’s not surprising that time appears to accelerate as we grow older.

We commonly think of our lives in terms of decades – our 20s, our 30s and so on – which suggests an equal weight to each period. However, on the logarithmic scale, we perceive different periods of time as the same length. The following differences in age would be perceived the same under this theory: five to ten, ten to 20, 20 to 40 and 40 to 80.

I don’t wish to end on a depressing note, but the five-year period you experienced between the ages of five and ten could feel just as long as the period between the ages of 40 and 80.

So get busy. Time flies, whether you’re having fun or not. And it’s flying faster and faster every day.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Chemical and Advanced MaterialsSee all

Kate Whiting and Simon Torkington

February 22, 2024

Adam Rothman, Charlie Tan and Jorgen Sandstrom

January 30, 2024

Jemilah Mahmood, Douglas McCauley and Mauricio Cárdenas

January 15, 2024

Ronald Haddock

January 4, 2024

Lee Jongku and Rafael Cayuela

January 4, 2024