Ever searched for your keys on an empty desk? This is why

Most of us waste a lot of time looking for objects. Image: REUTERS/Stefan Wermuth

Imagine that you are searching for your house keys, and you know they could be on either of two desks. The top of one desk is clean, while the other desk is cluttered with papers, stationary, books and coffee cups. What is the fastest way to find your keys?

Looking around on the surface of the empty desk is clearly a waste of time: the keys on an empty desk would be easy to spot, even in the visual periphery. An optimal search strategy would be to spend all your time searching the cluttered desk.

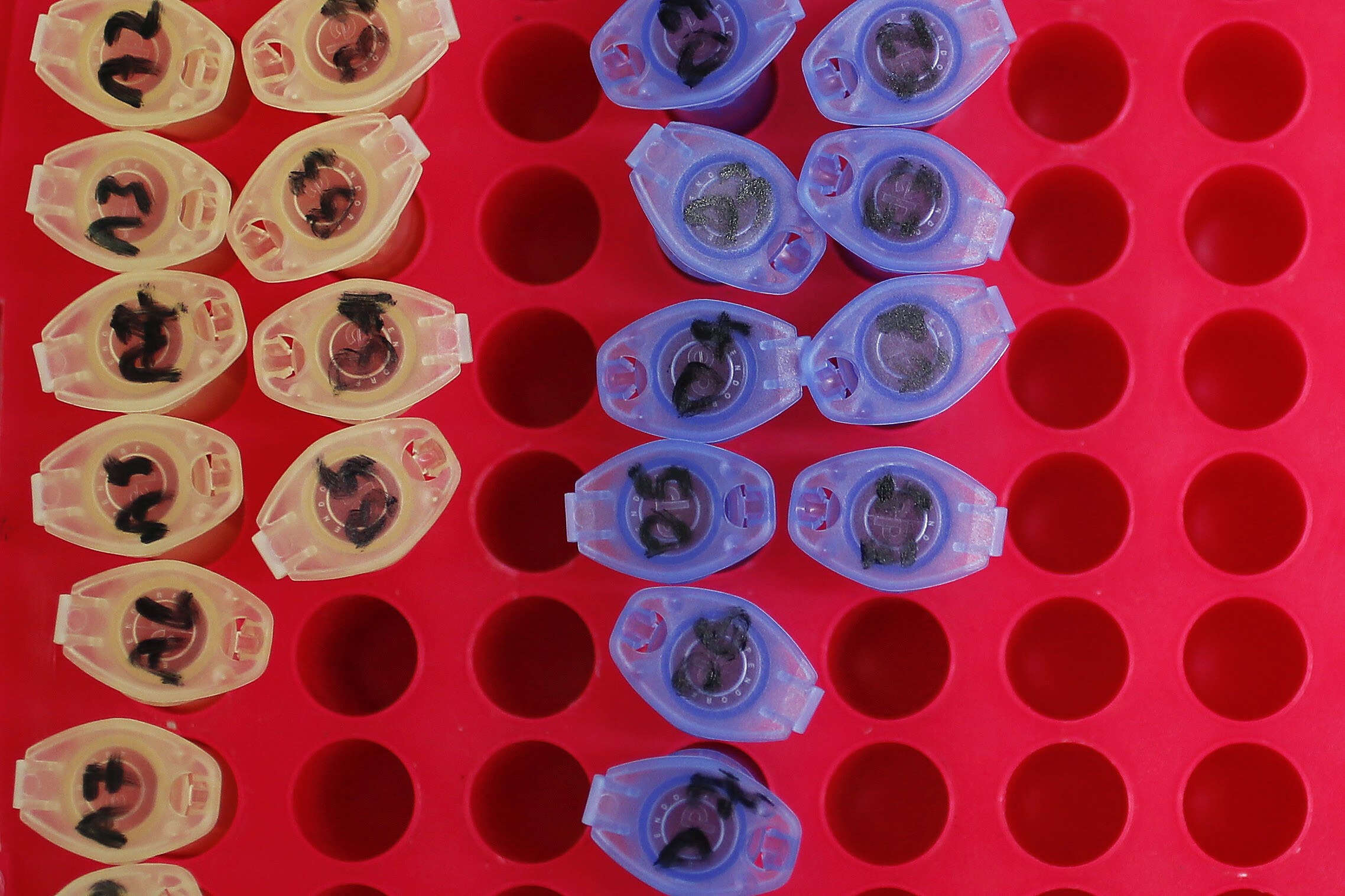

But is this what we actually do? We wanted to find out, so we set up an experiment to test the efficiency of human search by manipulating the background to make a search target pop out on one half of a computer screen and blend in on the other half. We monitored eye movements in participants using a high-speed infrared camera. The optimal search strategy in this experiment is not to look at the easy half of the display at all, because it gives you no new information.

But our results, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, reveal that most of us do not use such an optimal approach at all. In fact, the 28 observers in our two experiments, as a group, directed almost half of their eye movements to the easy side, and these ineffective eye movements slowed down the search substantially. Intriguingly, we also found very large individual differences. Some observers concentrated their search on the difficult side, some concentrated on the easy side, and some split their attention between the two.

But why are people looking at the easy side, even though it only slows them down to do so? It could be that, like in our example with the keys on the desk, people systematically fail to look in places that provide the most information. It’s also possible that people just make a lot of unnecessary eye movements to both sides of the display.

Optimal foraging?

To find out which option is more likely to be the cause, we used a mix of easy and hard displays – some of them on a uniform screen and some of them split into two screens. The participants’ task was to indicate if a line tilted 45 degrees to the right was present or absent on a given trial (see below).

We found that people spent a disproportionate amount of time searching on the split screens. This suggests people were quite bad at looking in the places that provide them with the most information, rather than just making unnecessary eye movements. However we also found that participants made many more eye movements than they needed to. They don’t need to move their eyes at all to see the target on the easy background, but people made an average of seven eye movements before saying if the target was there or not.

The results have important implications for competing models of how humans perform visual searches. One influential theory claims that human (and many other species’) performance in visual search tasks is consistent with an “optimal foraging” strategy, in which a target is found in the smallest possible number of eye movements by rapidly calculating which locations will provide the most information.

An alternative model suggests that a random search strategy can achieve similar levels of performance under the right conditions. This model correctly predicts the group-level results in this new experiment.

But this doesn’t apply when we take into account how individuals behave. Some individuals have eye movements that match an optimal strategy quite closely. Others could be described as “random”. Others still could be described as anti-optimal: these people spent almost all their time searching the easy side. Given the wide range of variation between people we observed, we think it may not be possible to describe search with a single model. Our next step is therefore to better understand individual differences in search strategies, to be able to form more complete and accurate models of how humans search.

In the meantime, in practical terms, our results suggest most of us waste a lot of time looking for objects. To be more efficient, we should not look at the empty surfaces, but direct our search to locations with the most clutter.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Neuroscience

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.