Progress despite uncertainty: Key findings from the Global Gender Gap Report 2025

It will take 123 years to reach gender parity, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2025. Image: Getty Images

- It will take 123 years to reach gender parity, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2025.

- Iceland tops the ranking for the 16th year in a row.

- Accelerating action towards gender parity can boost growth and resilience in the face of economic uncertainty.

123 years. That’s how long it will take to reach gender parity, according to the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Gender Gap Report.

It’s a long time, but in 2024 that figure was 132 years, so we’ve come 11 years closer to full gender parity in the past 12 months.

The reason for such progress, however narrow, might just be because, amid the uncertainty, gender parity is essential for economic growth and resilience.

Economies that have historically invested in developing their full human capital – both women and men – tend to be more sustainable and prosperous.

When you tap into the complete talent pool and benefit from diverse perspectives, you unlock creativity and innovation that drives real growth and productivity.

The Global Gender Gap 2025

The Forum has been tracking global progress towards gender parity since 2006, making it the longest-standing index of its kind.

The 19th edition looks at the status of parity across four dimensions – Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment. It takes in 148 economies, representing two-thirds of the world’s population or around 75% of the world's economies.

Overall, 68.8% of the global gender gap has been closed, up 0.3 percentage points from last year.

The Index finds a notable build in momentum in 2024, with improvements in 11 out of 14 indicators measured, and a speed of progress that puts us almost back on a pre-pandemic trajectory to closing the gap.

Top performers among lower-income groups have closed a greater share of their gender gaps than over half of the high-income economies.

Despite this, parity is still 123 years away, and no single economy has achieved full gender parity. While collectively we have narrowed the gap by 4.8 percentage points since the index was launched, significant gaps remain in economic and political parity.

The top 10 economies for gender parity

Iceland comes top for the 16th consecutive year with 92.6% of its gender gap closed – still the only economy to have closed more than 90% of its gap – while Europe once again dominates the top 10.

The top three economies are all Nordic nations, with Finland and Norway ranked second and third, respectively – the same positions as 2024.

The UK has made a significant jump to fourth place - from 14th in 2024 – with 83.8% of the gap closed. This is largely due to its historic, gender-equal cabinet and an increase in the number of women in the parliament, which has taken its Political Empowerment score from 47.4% in 2024 to 64.3% in 2025.

The Republic of Moldova is also one of the new entries in the top 10, ranking seventh up from 13th, with 81.3% of its gap closed, and more than tripling its political parity score since 2006.

New Zealand is one of the only two non-European economies in the top 10, but drops to fifth from fourth last year, while the other, Namibia, maintains its position in eighth with 81.1% of its gender gap closed.

Economies ‘sprinting’ to parity

Overall, there are three regions positioned to close their gap within the next century.

Latin America and the Caribbean is the standout region, on track to reach parity in 57 years. The region has advanced 8.6 percentage points since 2006, showing rapid, coordinated progress is achievable.

Europe follows at 76 years to parity, then Northern America at 89 years, if the trend continues. At the other end, Central Asia faces 208 years, and Middle East and Northern Africa 185 years.

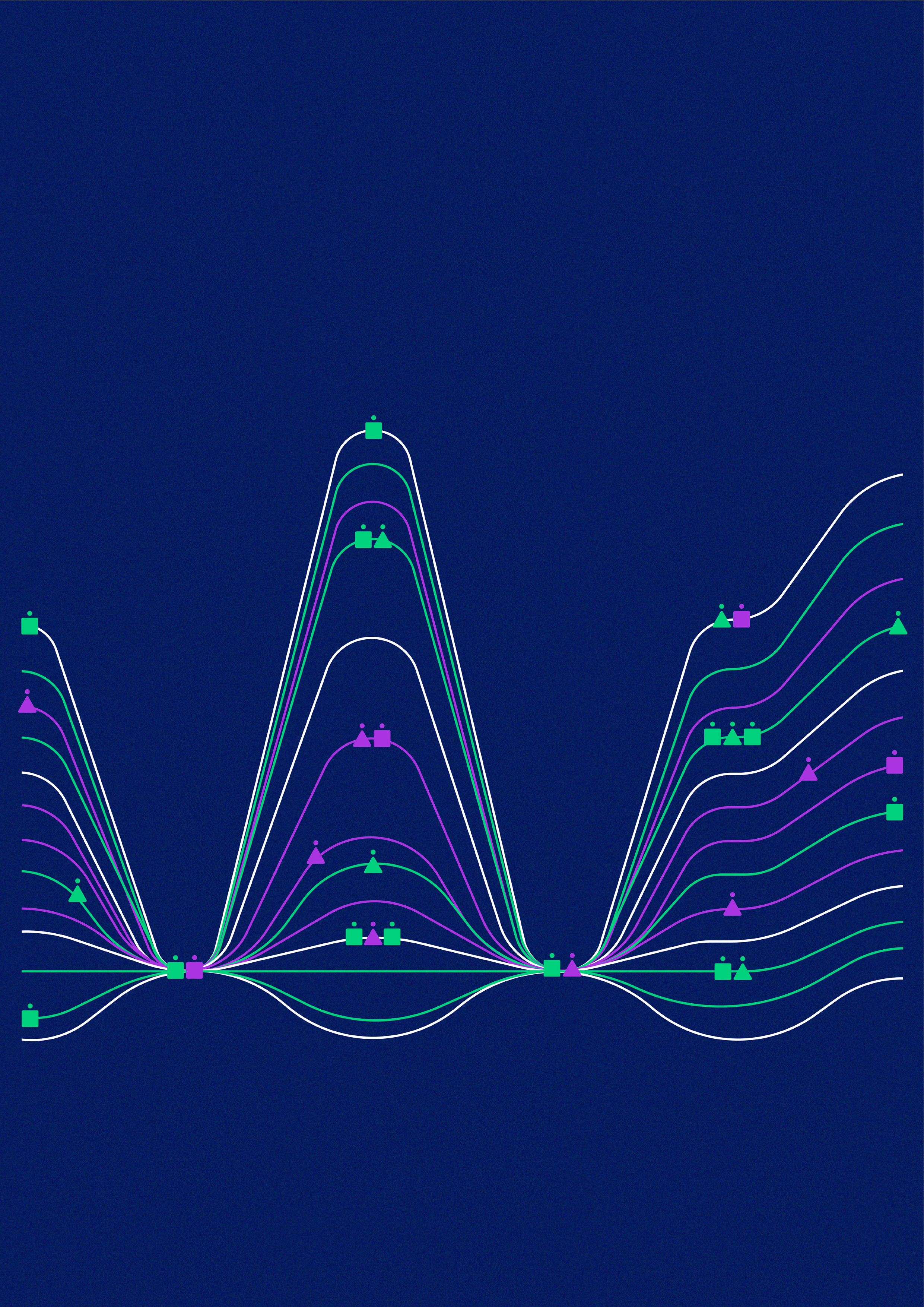

Outside of regional blocks, the report analyzes the individual trajectories that 100 economies have been following over time.

Grouping them by their speed of progress, we are able to spot those that are moving forward at higher velocity than others. Eight of them, including Bangladesh, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Mexico and Saudi Arabia, are 'sprinting' to parity.

When we group them by income level, we see a clear pattern: in every income group, economies are pulling ahead.

The state of the 4 gender gaps

None of the four gender gaps measured is completely closed.

However, while disparity remains highest in political and economic dimensions of the index, substantive progress has been recorded to date in these subindexes.

Since 2006, there are now more senior women officials, managers and legislators (up 17.5 percentage points in parity score), more women in professional and technical roles (up 7.3 percentage points), in ministerial positions (up 12.6 percentage points) and in legislative bodies (up 14.7 percentage points).

But women remain underrepresented in ministerial positions that shape economic strategy, defence and infrastructure, portfolios that are particularly critical in today’s complex geopolitical and economic landscape.

Closing gender gaps for renewed growth

With 82% of chief economists thinking global economic uncertainty is currently very high, according to a May 2025 survey by the Forum, levelling the playing field by accelerating action towards gender parity could be a stabilizing force for good.

But inaction and hesitation are delaying full equality and undermining economic resilience – through underused talent, lost productivity, slower innovation and frayed social cohesion.

Simply put: if women benefit, everyone benefits.

With fewer than five years left to meet the SDG 2030 targets, now is the time for economies to double down on these efforts and accelerate action.

Here are five ways to advance gender parity:

1. Workforce participation and senior leadership: Despite progress in women’s workforce participation, gender-based industry segregation persists, with women still concentrated in lower-paying, people-centric industries like healthcare and education. A greater balance between women and men’s cross-industry representation would support creativity and innovation, close wage gaps, amid technology transformation and demographic shifts.

2. Returns on education investment: Increasingly, women are outperforming men at tertiary education. Despite this, they remain underrepresented in the workforce and in leadership roles — only 29.5% of tertiary educated senior managers are women. This mismatch highlights systemic inefficiencies in translating skill preparedness into economic engagement and leadership. As younger generations become the face of the global workforce, an opportunity emerges for decision-makers to seize long-term talent dividends by ensuring the workforce integrates male and female workers.

3. Career pathways: Nonlinear career paths are becoming more common, especially among women. As an economic solution to both demographic and workforce transitions, the care economy remains underleveraged. Robust care systems can improve workforce planning and economic productivity by supporting parents and caregivers who seek a different balance. Currently women are 55.2% more likely than men to take career breaks, and for longer durations (19.6 months vs. 13.9 months) largely due to full-time parenting.

4. Political leadership: Globally, women remain significantly underrepresented in the political sphere, including legislative bodies — where they represent fewer than one-third of parliamentary speakers. Across legislative institutions, there are 161 bodies with a gender equality mandate, leadership of which remains predominantly female. Women are also underrepresented in cabinet portfolios such as economy, infrastructure, and defence — a distribution with tangible economic consequences in the shaping of national priorities and public investment.

5. The role of legal frameworks: A major barrier to progress is the “implementation gap” — the disconnect between gender-equal laws and the infrastructure needed to enforce them. Across economies included in the index, there is a near-universal implementation gap. Even economies with advanced legal frameworks show wide differences in practical support. Adopting high legal standards alone is insufficient to close gender gaps; robust implementation mechanisms are key to translating policy into real gender parity outcomes.

Have you read?

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Elizabeth Mills and Gayle Markovitz

January 30, 2026