What's in a number? How economic data (should) drive decisions

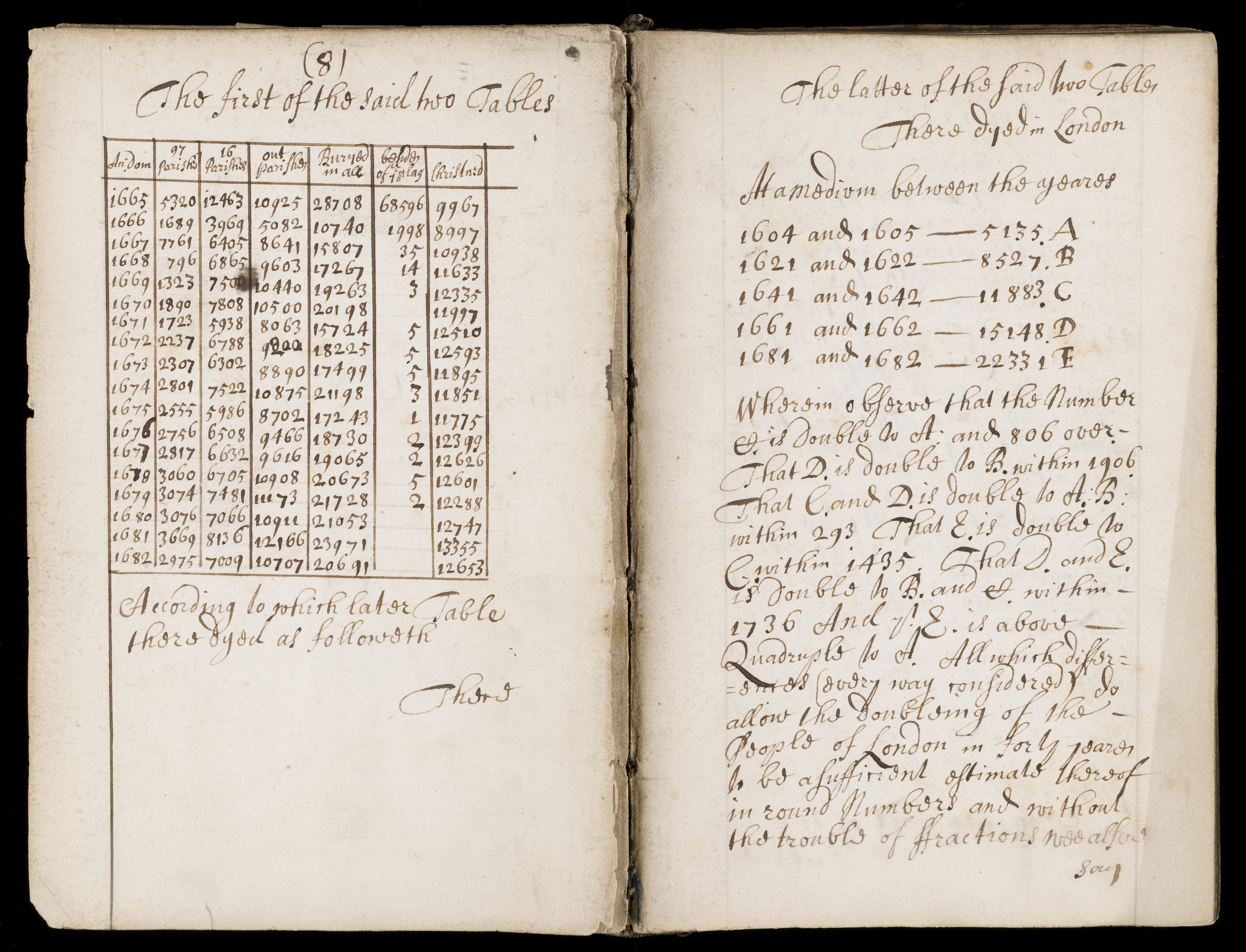

The accuracy of employment figures and other economic data has been a cause for concern for centuries. Image: Wellcome Library, London

- The value of accurate and unbiased economic data is receiving renewed attention.

- Businesses need solid figures to plan ahead, and public officials require them to make far-reaching decisions on spending and managing the money supply.

- History demonstrates that truth-in-data is oxygen for an economy.

Who needs democracy?

A lot of people, apparently. When a former government official from Greece saw fit to issue a plea earlier this year to preserve something essential for “the functioning of democracy itself,” heads turned.

The subject of his juicy take? The very dry business of publishing trustworthy economic data.

The normally low-profile public servants who churn out tables and charts on a regular basis, and dutifully revise as needed, are illuminating lighthouses that prevent policy-makers from blindly crashing an economy on rocky shoals.

Should we lower interest rates? Better have solid inflation and employment figures on hand. How about investing in a new factory? Hopefully industrious clerks are at the ready to provide reliable numbers on the local labour market and energy costs.

Yet, a decision earlier this week in the US to lower rates appears to have been made at least partly on a hunch. That’s because official job-creation data that normally informs the call may be overstated at the moment, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said.

When the ancient Greeks sought economic counsel, they turned to a guy strumming a lyre and reciting poems; Hesiod’s verse jibed with the labour theory of value, and was probably more enjoyable than a press release. It was also more accurate than the official budget-deficit figures modern Greece relied on in the first years of this century, which eventually turned out to have been under-reported. A worsened debt crisis and punishing austerity followed.

Other historical examples of bogus information inflicting real damage include the agricultural statistics in the Soviet Union that were often intended solely to hit arbitrary quotas. Political factors there spawned a system liable to overestimate grain harvests, and lead to shortages.

In the US, a combination of outdated models and problematic ratings on the safety of mortgage-backed securities stoked the 2008 global financial crisis. More recently, that country’s jobs statistics started to become news in August – when a dramatic, downward revision to a pair of monthly figures aroused presidential ire.

As economists argued for maintaining the sanctity of data no matter whom it upsets, an international framework designed to help do just that was being revamped.

An updated System of National Accounts was approved earlier this year, and is wending its way around the world. It’s an international standard for measuring a country’s economic fundamentals: production, consumption, investment, and wealth.

Have you read?

The lofty benefits promised by technology made the need for a global measurement refresh more pressing. Nearly $100 billion in added economic well-being was enjoyed in the US alone last year thanks to artificial intelligence, according to one estimate – but none of that registered in traditional metrics.

Getting the 'arithmetick' right

The British economist William Petty’s Political Arithmetick was published in 1690. It popularized the fledgling concept of applying numerical analysis to economics, and included its own sort of jobs report: “The Husbandman of England earns but about 4 s. per Week, but the Seamen have as good as 12 s.” People have been bickering about the accuracy of these kinds of figures ever since.

The same US labour-statistics agency that has lately incurred the wrath of the White House also found itself in political crosshairs back in 2012. That time, it was an unemployment rate that seemed too good to be true.

322 years earlier, Political Arithmetick sought to pre-empt any 17th-century political backlash with a preface carefully explaining that its overriding aim was “to shew the weight and importance of the English Crown.”

In the 21st century, some say it might be best to entirely remove the production of economic figures and other sensitive information from direct political supervision. The ex-Greek government official whose recent appeal for data integrity drew attention certainly thinks so. He still faces legal action for his role in correcting the official record in his country more than a decade ago. Meanwhile the pain of subsequent austerity measures there has left a lasting imprint.

Other suggestions for ways to bolster faith in economic data include better explaining the process behind it. US jobs reports provide a good example. Revisions to these numbers are nothing new, which is something most people might not know.

Each month’s new-jobs figure is based on surveys distributed to hundreds of thousands of businesses. It takes a while for many of them to respond.

In the meantime the initial data gets published even if it's premature – but is then refined once the bulk of responses are in hand a few months later. A particularly big revision may signal a significant swing in the economy. It’s a bit like a journalist rewriting months-old copy at least a couple of times to get it right. Or, more right.

Agencies may be able to better flesh out data like this for the public, but other aspects of the job sit further outside of their direct control. Like response rates.

A few years ago, responses compiled for the UK’s benchmark jobs report plummeted so dramatically that its publication was disrupted. That left the country’s central bank in the dark as it sought to set interest rates, with billions of pounds for the economy hanging in the balance. Officials have since considered making responses legally mandatory.

Falling short like that is one thing, fudging is another. Both are equally represented in the annals of history.

Economic data has been likened to vital infrastructure, and to a free information service for investors. The erstwhile Greek government official who recently sounded an alarm chose to compare it to a mirror. Dim the lamp and preen all you want, but you’ll still look the same in the cold light of day.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Sarah Sáenz Hernández

February 24, 2026