World University Rankings 2026: Is the geopolitics of knowledge and innovation shifting?

The traditionally dominant Western universities are steadily losing ground to Asian schools, according to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Image: Unsplash/BunlyHort

- Many long-running trends have continued in the latest Times Higher Education World University Rankings, but new themes are also emerging.

- The University of Oxford has held the number one spot for 10 years running, while China now has five top 40 universities, up from three last year.

- Centres of research and innovation across Asia are increasingly competing with Western universities.

A new world order for higher education, research and innovation is emerging, data from the latest Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings suggests.

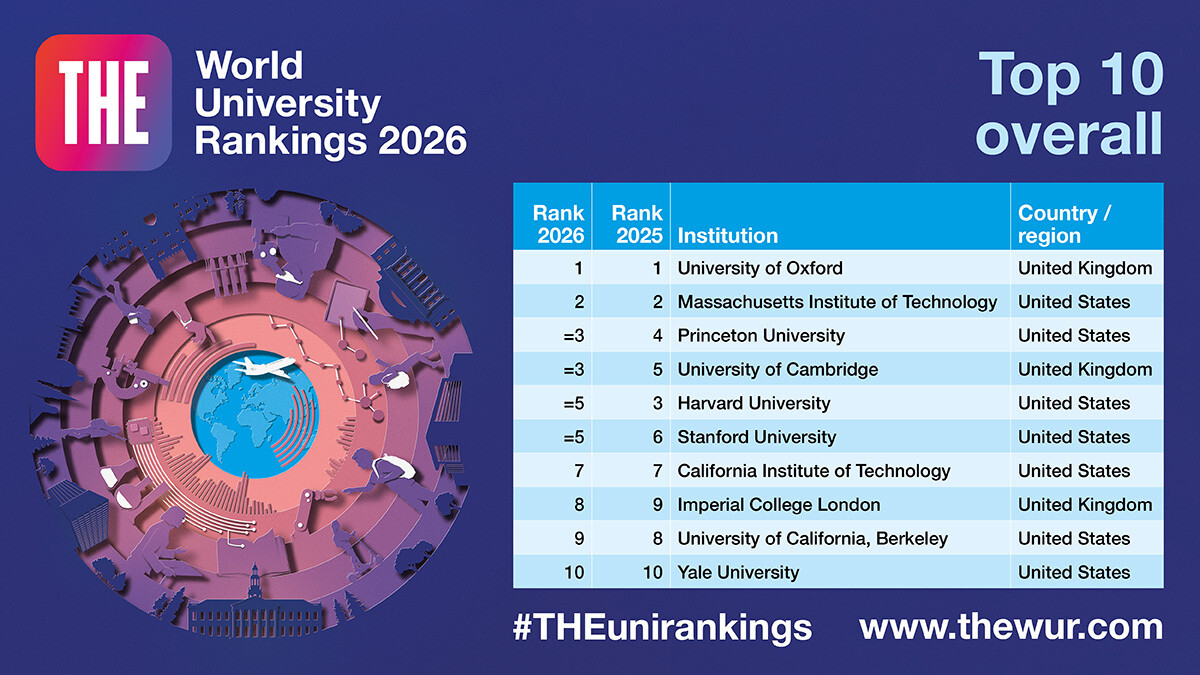

At first glance, the 2026 edition of the rankings looks predictably familiar: The UK’s ancient University of Oxford is world number one for the 10th consecutive year and the US continues to dominate the upper echelons of the rankings. It's home to no fewer than seven of the world’s top 10 universities, including world-leading university brands the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2nd) and Princeton (joint 3rd).

But look more closely at the data, which evaluates more than 3,100 universities from 136 countries, and a powerful and accelerating trend becomes clear. The traditionally dominant Western powers, across North America and Western Europe, are steadily losing ground to a rising Asia, led by China. This signals a major shift in the geopolitics of knowledge and innovation.

The World University Rankings use tens of millions of data points to assess the leading research universities across 17 comprehensive performance metrics, covering the teaching environment, academic reputation, international outlook in research and talent attraction, research strength and industry-linked innovation.

US and UK universities are losing ground

In the US, while 19 American universities have risen up the latest rankings, a remarkable 62 have lost ground. Well-known names like the University of Chicago (15th), Columbia (20th) and Duke (28th) have suffered their worst-ever ranking positions (albeit from relatively high places). And while the US still dominates the world top 500, with 102 institutions in that elite group, this is America’s lowest top 500 tally.

In the UK, the number of universities that have fallen is more than double the number that made improvements, at 28 versus 13 respectively. And, as with the US, this year marks a record low for UK representation in the world top 500 – it’s down to 49 higher education institutions.

These downward pressures continue a longer-term trend. It could also signal a new direction of travel as data from the 2026 rankings largely pre-dates the deep research funding cuts and international talent visa restrictions implemented in the US in recent months. This year's rankings don't take full account of the UK university sector’s funding crisis either, with course closures and mass redundancies being made throughout 2025.

As Irene Tracy, vice chancellor of the University of Oxford told THE, while Oxford’s success as world number one “reflects the dedication of our academics, professional services staff and students, it comes at a time of real strain for UK higher education.

“Sustaining a dynamic and globally competitive sector requires renewed investment and support, so that universities can continue to drive discovery, opportunity and economic growth for future generations,” she adds.

Across Europe, there are similar concerns. Germany has six universities rising in the rankings and 22 falling. France has three up but 22 down. Spain has two rising and 10 falling. The Netherlands has seen eight of its 12 universities slipping down the rankings.

The rise of Asian universities

The contrast with key Asian nations could not be more stark.

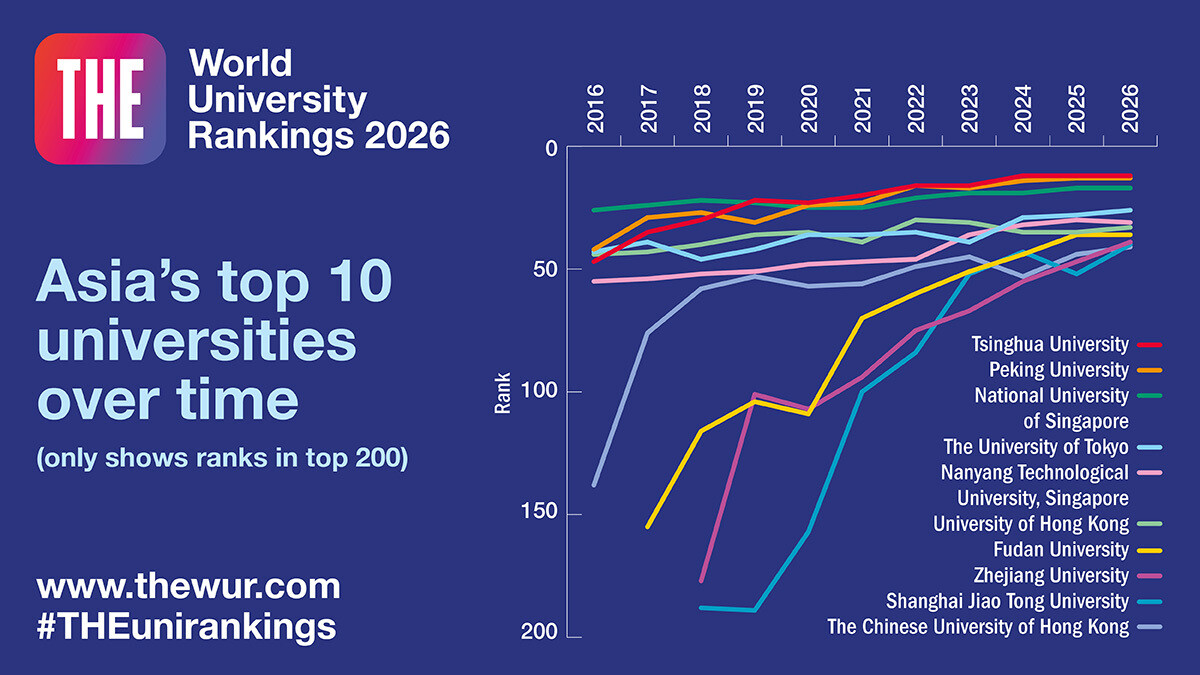

While mainland China’s top two flagship universities have held their positions (Tsinghua University in 12th place and Peking University in 13th overall), 18 Chinese universities have achieved their best-ever positions. This includes Zhejiang University (up eight places to 39th) and Shanghai Jiao Tong University (up 12 places to 40th). Both have moved into the top 40 for the first time, overtaking America’s Georgia Institute of Technology (joint 41st) and Canada’s McGill University (joint 41st) and University of British Columbia (45th) in the process.

China now has five universities in the top 40, up from three last year, and 35 in the top 500 – which is more than Australia.

Every one of Hong Kong’s six universities ranked last year has risen, led by University of Hong Kong, which moved up to 33rd from 35th. It has also added two new entrants to the rankings this year, securing a record six universities in the top 200, as well as two in the top 350. South Korea rises significantly in all four research quality metrics and has 10 universities rising, and only four slipping. It now has a record four higher education institutions in the top 100.

And beyond the East Asian powerhouses, new geographical centres of research and innovation are emerging.

In South East Asia, Indonesia is the most improved of all larger nations in the world in terms of its overall rankings score, while Malaysia has six rising universities and just one slipping. Thailand’s flagship, Chulalongkorn University, has jumped into the world top 600 for the first time.

There are also new geopolitical alliances in scientific research, for example across Central Europe and the Turkic states. This is led by a surging Turkey, which is now the joint fourth best represented nation in the world rankings (with 109 ranked universities). It has 11 rising universities and only three falling, with the others stable.

In the Middle East, Saudi Arabia is leading a new Arab world renaissance, with nine rising universities against four that have slipped.

Higher education disruptors

So does the data point to a dramatically different world order in higher education, research and innovation in the coming decades?

Alan Ruby, a senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, suggests that a tipping point from West to East is far from inevitable but that momentum may be on the side of the emerging new regions.

“Would you bet against the accumulated expertise, established infrastructure and wealth of the old institutions?” he asks. “These are entities that have survived plagues, wars, insurrections, anti-intellectualism, loyalty tests and religious persecution and intolerance.

“Or would you back the disruptors, the agile, the institutions that are free of the shackles of precedent, privilege and public regulation? As I weigh these choices I recall the maxim of organizational theorist Jason Kelce, known more for his prowess on the Philadelphia football team, that it is hungry dogs that run faster.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

United States

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Education and SkillsSee all

Mohamed Abdel Latif

February 4, 2026