Opinion

5 prominent geoengineering ideas — and why they will not save the poles

Geoengineering seeks to counteract the effects of global warming. Image: Derek Oyen/Unsplash

Martin Siegert

Polar Scientist, Deputy Vice Chancellor, University of ExeterHeïdi Sevestre

Glaciologist and Deputy Secretary, Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme Secretariat- Climate change is reshaping every region on Earth, but the Arctic and Antarctica are warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet.

- Technological interventions – known as geoengineering – have been proposed to slow the impacts of global warming at the poles.

- However, each of the proposed geoengineering techniques faces serious scientific, environmental, political or economic barriers.

Climate change is reshaping every region of the Earth, but nowhere is the pace faster than in the Arctic and Antarctic.

The polar regions are warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the planet, resulting in rapidly shrinking sea ice, retreating glaciers and collapsing ice shelves – changes that threaten fragile ecosystems and drive global sea-level rise.

Some scientists and engineers have proposed technological interventions – known as geoengineering – to slow or mask the impacts of warming at the poles.

None, we found, holds up to scrutiny, as each faces serious scientific, environmental, political or economic barriers, as outlined in our recent Frontiers in Science article.

Five geoengineering ideas that face barriers

Here, we summarize five prominent geoengineering ideas and how they fall short.

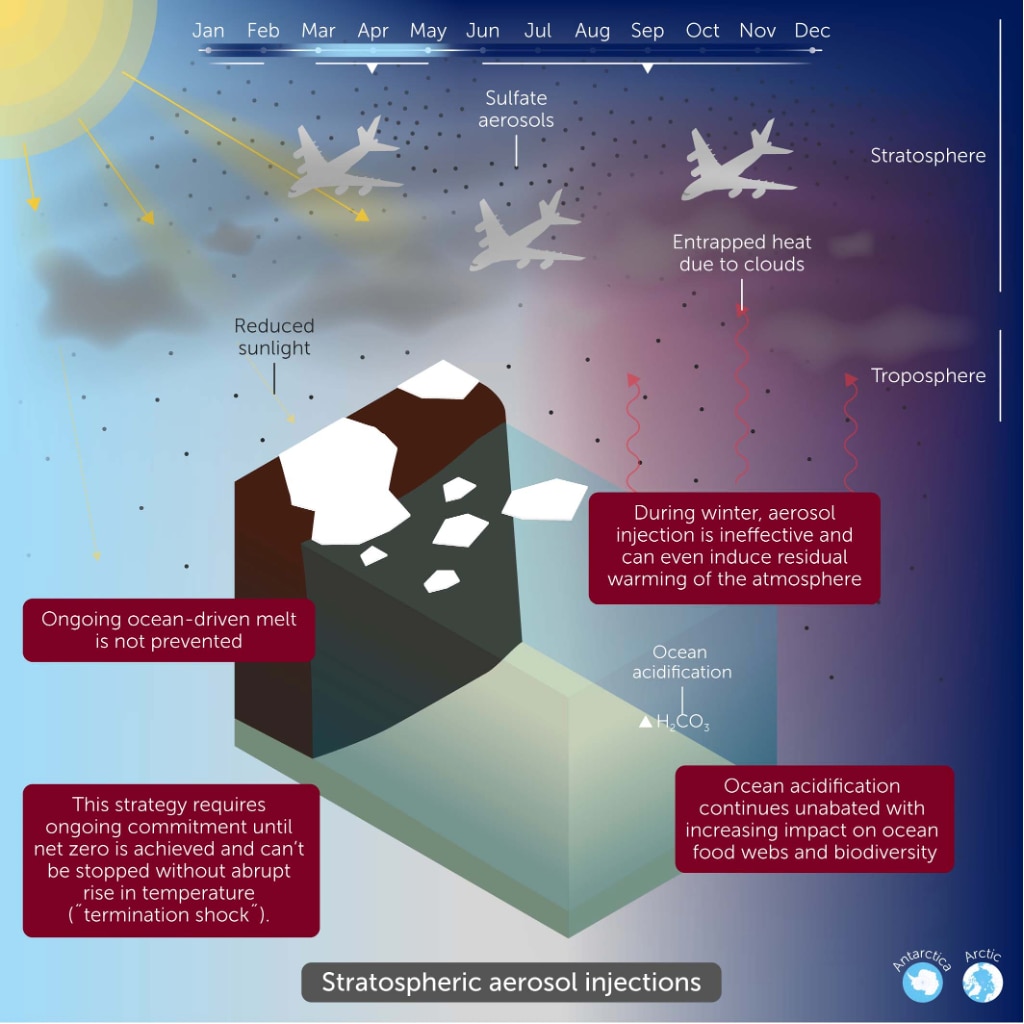

1. Stratospheric aerosol injection

Stratospheric aerosol injection involves spraying reflective particles, such as sulfates, into the stratosphere – the layer of the atmosphere that begins about 10-15 km above Earth’s surface.

Particles could be delivered by multiple methods, including a fleet of custom-built aircraft, spreading them widely enough to form a reflective haze. Data from major volcanic eruptions suggest this haze could reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching the surface and temporarily reduce surface temperatures.

However, sulphates can react with other chemicals in the stratosphere, destroying ozone molecules and thus thinning the protective layer that shields life from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

A widespread aerosol haze could also change how heat moves through the atmosphere, shifting rainfall belts – creating drought risks in some regions and flooding in others. If deployment were ever halted abruptly, a dangerous temperature rebound termed “termination shock” could cause global temperatures to surge within a few years. Furthermore, cooling the planet via stratospheric aerosol without reductions in greenhouse gas emissions would lead to continued ocean acidification.

2. Sea curtains

The sea curtain concept involves vast underwater barriers designed to block warm ocean currents from reaching the marine portions of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. This is where the ice sheets are most vulnerable, and preventing relatively warm water from eroding them could, in theory, slow ice loss and limit sea-level rise.

Curtains could be built from flexible fabric or other strong, buoyant materials and anchored to the seabed, rising hundreds of meters through the water column. Constructing such barriers in the harsh polar seas would be extraordinarily difficult.

Once built, storms and collisions with drifting icebergs could tear or sink them, requiring constant maintenance. By blocking currents, the curtains could alter the way heat and nutrients circulate near the ice-ocean boundary, potentially accelerating ice loss in some regions while starving others of nutrients.

3. Sea ice management

Sea ice naturally reflects sunlight back into space, helping to cool the planet. As the ice diminishes, some have suggested artificially enhancing its reflectivity or thickness to counter further loss. Ideas include scattering tiny glass microbeads across the surface so that the remaining ice reflects more sunlight, or using pumps or other engineering methods to thicken sea ice during the winter, with the hope that it would persist longer into the summer melt season.

The vast quantities of beads required would pollute fragile polar ecosystems. Beads could be ingested by plankton and other small organisms, contaminating food webs and altering the ocean’s chemical cycles. Artificially thickening ice at the necessary scale would require millions of pumps working through extreme winters, with enormous power demands and significant pollution risk. Moreover, the process would take decades or longer to have any meaningful effect on the pace of sea-ice loss, making the concept an impractical solution.

4. Basal water removal

Glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica rest on a bed, and where water is present at this bed, the ice above can move seaward at enhanced speed. Basal water removal involves drilling through the ice to pump this water away. By reducing the lubrication under the ice, engineers hope to increase friction at the glacier’s base, slowing its movement toward the ocean and limiting ice loss.

The geological structures beneath major ice sheets are complex and poorly mapped, making it difficult to predict whether pumping would actually slow ice flow or merely redirect it. Drilling and maintaining pumping stations in extreme polar conditions would demand heavy machinery and huge energy supplies, with a high risk of mechanical failure and pollution.

Even small-scale experiments are likely decades away – and scaling up to influence entire ice sheets is beyond current engineering capacity. The subglacial water system is perhaps the last place on Earth that is truly isolated from any human interference. This concept would be an intentional destruction of this last pristine environment.

5. Ocean fertilization

Ocean fertilization aims to trigger blooms of phytoplankton – microscopic algae that absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis – by adding iron or other nutrients to the nutrient-poor waters of the Southern Ocean. When the plankton die they sink into the deep ocean, taking some of the absorbed carbon with them. Advocates argue that this process could lock away significant amounts of carbon to help slow climate change.

Trials over the past two decades have shown little evidence that fertilization reliably stores carbon. Instead, sudden algal blooms could disrupt marine food webs, favouring some species while starving others, and can release harmful toxins. Adding iron can also alter nutrient balances in distant waters connected by ocean circulation. International regulations currently restrict large-scale ocean fertilization under marine pollution agreements, leaving the approach with no clear path forward.

Decarbonization remains the best solution

As highlighted here and detailed in Frontiers in Science, none of these geoengineering ideas can currently be relied upon to safeguard the Arctic or Antarctic.

They are scientifically uncertain, technically infeasible and environmentally risky. All would prove enormously costly and require new global governance structures and unprecedented political consensus. More importantly, pursuing them risks distracting from the solutions we already know will work.

Reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions remains the clearest and fastest way to stabilize the climate. Unlike geoengineering, decarbonization relies on technologies and strategies currently available and deployable at scale, and where international agreement has been established.

Once global emissions are eliminated, warming will slow and then stop, bringing substantial benefits to the polar regions, the planet and people everywhere. Only evidence-based strategies – not speculative shortcuts – can help build the trust and capacity needed for real climate action.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Climate Crisis

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

David Costa

February 5, 2026