How data centres and AI are becoming a new engine of growth

An increase in the construction of data centres is driving economic growth. Image: Unsplash/Geoffrey Moffett

- The surge in data centre construction and AI-related spending has become a significant driver of business investment and GDP growth, especially in the United States.

- Hyperscalers such as Microsoft, Alphabet and Meta are at the centre of this investment wave, giving the US more than 40% of global data centre capacity.

- The combination of strong GDP growth and weakening employment growth suggests early productivity improvements from AI adoption.

Data centre construction and related artificial intelligence (AI) investment have surged in recent years. This is a global story, part of a worldwide AI race turbocharged by the launch of technologies such as ChatGPT. This race has multiple dimensions, spanning economics, geopolitics, energy and technology.

In a macro context, the data centre boom centres on business investment, boosting current growth and shaping labour demand, and ultimately, productivity and medium-term growth.

The data centre macro story extends well beyond the construction of physical buildings. In this sense, the term “data centres” understates the macro impact of AI build-out. Mapping the AI boom to investment has several components in the national accounts.

The first is the construction of data centres and the related investment in power, captured under non-residential buildings. The second is investment in the high-tech equipment needed to operate these facilities, including racks, servers, mainframes and cooling systems. The third is intangible investment, including the software needed to run data centre equipment.

US leads in global data centre build-out

The main economic actors in the data centre build-out are hyperscalers such as Microsoft, Alphabet and Meta, which provide large-scale cloud computing services. Their central role in the AI and data centre race represents an interesting twist in their macro story.

Historically, the tech industry has been viewed as human capital-heavy with a light capital expenditure footprint. However, with the build-out of large data centres and the race for AI dominance, the tech firms’ macro footprint is starting to resemble that of manufacturing. Data centre colocation providers offering a shared-space model also contribute a sizable share to data centre construction.

While the AI race is global, the United States is leading. This reflects the scale of investments and the computing capacity necessary to run large language models. S&P Global Market Intelligence 451 Research estimates that US data centre capacity represents more than 40% of the global total and that figure is projected to continue growing. Asia-Pacific follows, with Europe a distant third.

Offsetting economic weakness

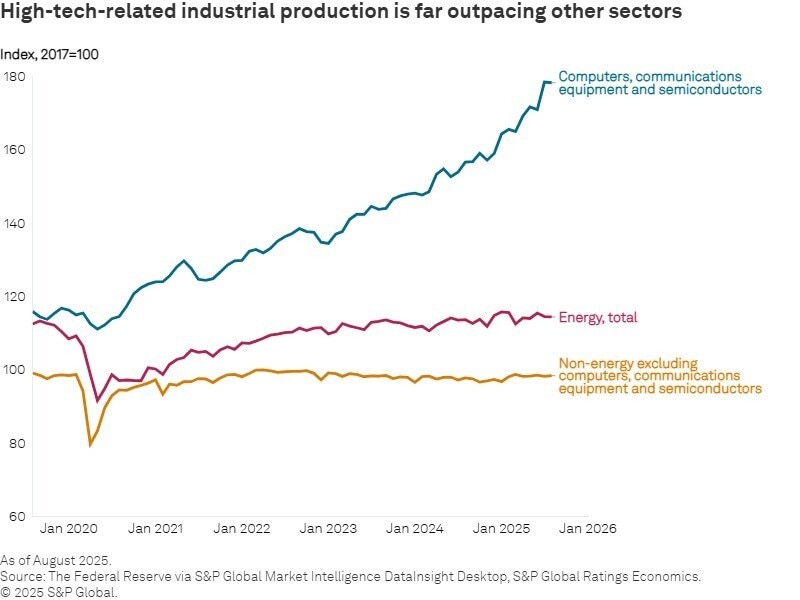

US macro data show that AI-related investments have surged in the past few years. This surge has persisted even as higher borrowing costs and policy uncertainty have weighed on other private investment. Indeed, business investment in AI is offsetting uncertainty-driven weakness in other investment areas and in the economy at large.

How does that map to macro? Data centres and related high-tech investment activities have recently become a key driver of US growth. Our estimate, based on official data by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, suggests that 80% of the increase in final private domestic demand in the first half of 2025 is attributable to data centres and related high-tech spending.

The importance of global data centres and high-tech spending to gross domestic product (GDP) growth is not straightforward. For example, most high-tech hardware used in US data centres is imported, with the surge beginning in late 2023.

This is a key channel through which the US data centre boom is lifting exports and growth elsewhere. The breakdown of US imports suggests that the main beneficiary economies have been Taiwan and Mexico.

However, Malaysia and South Korea have also shown recent increases, according to data from the US International Trade Commission. (Note that the standard trade data show country source, not country of ultimate ownership.)

Longer-term implications

While US GDP growth has remained stronger than expected over the past few quarters, employment growth has weakened. Although interestingly, tech employment is up in Europe, perhaps related to the boom in exports of high-tech software from Ireland to the United States.

The combination of positive GDP growth and flat employment suggests early productivity gains from AI, powered by data centres. Anecdotal evidence suggests that firms are already seeing productivity benefits.

Decreased demand for lower-skilled services may be the leading edge of a larger trend. And it may take time for these micro-level phenomena to percolate into the macro data. Nonetheless, the productivity benefits of AI may be realized more quickly than in the computer revolution of the 1980s.

In that era, Nobel Laureate Robert Solow famously quipped that “computers are everywhere except in the productivity data.”

Changes in the labour force, capital deepening and productivity drive GDP growth. So, the key question is: Will data centre investment strategies translate into sustained gains in productivity? And will any gains in productivity come with an augmented labour force or a reduced one? As noted above, we are already seeing hints of productivity gains, but the final picture will not be clear for years.

Economists’ estimates of the productivity payoff to growth from AI vary widely. We would note that these estimates project labour productivity growth, but they make no predictions about the growth of the labour force. Therefore, they do not predict whether GDP growth will be higher. Increases in labour productivity can have positive or negative effects on employment and labour force participation.

They can result in the displacement of workers, offsetting the growth effects of productivity gains or in the augmentation of workers’ output, boosting the growth effects.

Looking forward

The AI revolution is poised to be a major driver of economic activity for years to come. What will we do with any growth windfall? A recent example of this dynamic was the “peace dividend” after the end of the Cold War in the 1990s.

Firms and households will be better off, at least in aggregate. And options for spending the public sector’s windfall include tax cuts, paying down debt, building or repairing public infrastructure, funding the energy transition and investing in health as societies age, to name a few.

The AI revolution will also likely create distributional challenges, with strong implications for political economy, as we see from the effects of globalization. The role of labour and wage growth in an AI-enabled economy is, therefore, a key development to monitor. Public support for AI adoption will likely wane if negative distributional issues are ignored.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

The Digital Economy

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Artificial IntelligenceSee all

Stéphanie Thomson

January 28, 2026