3 things I learned at Davos 2026 on the future of finance: De-risking (less decoupling) and disorientation

"This year, fears of the end of globalization look overstated." Image: REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst/File Photo

- At Davos 2026, Oliver Wyman Vice Chair, Huw van Steenis sees a decisive shift toward economic statecraft.

- Artificial intelligence is no longer just a tech story but a macroeconomic force, driving unprecedented capital expenditure, financial risk and debate over productivity, employment and inflation.

- It's a disorienting time, investors are leaning on history and philosophy to make sense of the moment.

The mood in Davos was one of disorientation.

Mercantile economic policies, shifting geopolitical alignments and the dizzying advances in artificial intelligence are unsettling investors and decision makers, even as markets hover near record highs. The quotidian salvo of announcements is challenging even the steadiest hand to focus on the longer term.

Sitting across more than 40 private meetings and panels, I had access to the mindset of businesses, investors and policymakers. Here are three of my takeaways.

1. Broadening of economic statecraft

A central theme this year was how investors and policymakers are adapting to a more mercantile global order – one that emphasizes national security, self-reliance and strategic sectors. This is a painful and fiercely expensive paradigm shift for many at Davos.

Markets began pricing this shift last year, most visibly in US big tech, defence, minerals and energy, but this Annual Meeting marked a far broader reframing of national security to include finance itself.

As Mark Carney said, in one of the most compelling speeches of my 17-time Davos participation:

"Many countries are drawing the same conclusions that they must develop greater strategic autonomy, in energy, food, critical minerals, in finance and supply chains."

On a panel I hosted with Zanny Minton-Beddoes, editor-in-chief of The Economist, she described the shift more bluntly as a return to ‘gunboat diplomacy’ – a nudge that economic policy is once again an instrument of power, not just efficiency.

Despite indignation about supply chains being weaponized, my sense is that this is less decoupling and more de-risking to enhance resilience. For instance, reducing dependence on Chinese smelted rare earths is a strategic must, as is greater energy resilience.

The private debates quickly turned to the tails. How should Europe respond to US tech dominance? Or should Europe rely on American-owned payments rails?

The good news is that among the European financiers and policymakers the penny is finally dropping that future growth will require deeper and broader pools of capital.

As I argued in a pre-Davos Financial Times opinion piece, since 2018 securitization of US data-centre debt has totaled $63.6bn in the US, according to JPMorgan – $27bn of that in 2025 – compared with just $0.8bn in the EU. There is much to do.

There was a strong sense that 2026 has to be the year that Europe delivers on the ambitious reforms it set itself – in security, energy, digital innovation and finance – and go further. If Europe follows through, this would be positive for financials and growth.

Addressing the “chokepoints” will require sustained commitment, something Europe has often struggled to achieve. Large debt stacks growing faster than GDP and stubbornly high welfare expenditure only adds to the pressure. This reinforces why de-risking, rather than decoupling, remains the base case.

2. AI disruption: from micro to macro

AI dominated private sector discussions – as it does markets. If recent annual meetings were preoccupied with whether AI would transform industries, the 2026 debate focused on how to implement AI at scale.

Yet with scale comes complexity. Conversations on governance, cybersecurity risk and market structure were increasingly candid. There was a more balanced view that productivity gains can outweigh near-term organizational friction when adoption is thoughtful – though financial regulators still shudder at probabilistic models running some core processes.

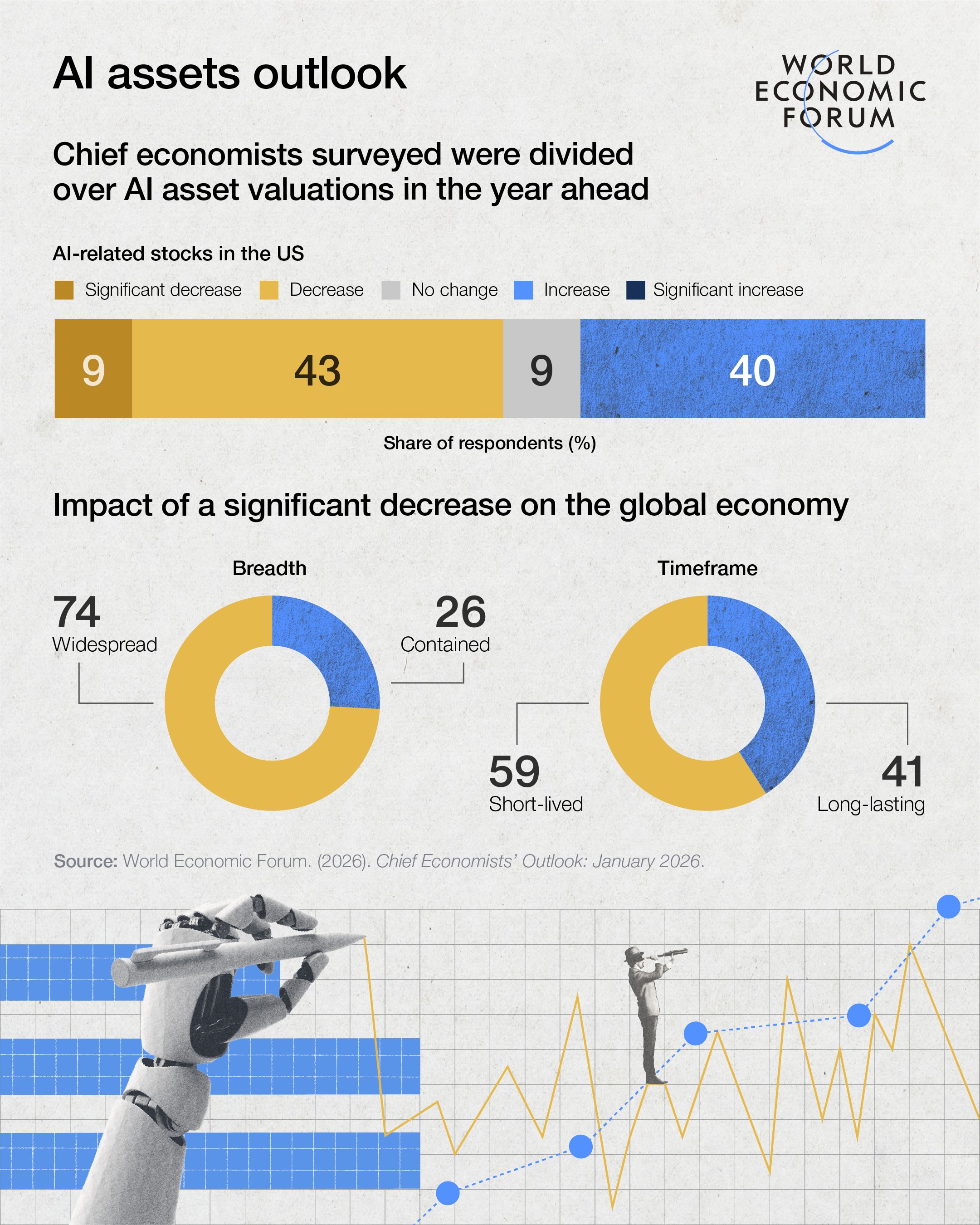

Whether the AI boom is a bubble waiting to pop is now a central investor question. Equity investors are already becoming more discerning. Market differentiation has widened sharply over the past year – visible in the growing valuation gap between the Google cohort and OpenAI partners. At the same time, many recognize the significant option value embedded in these investments which may or may not pay off, and the level of capex to revenues needing to be created is jaw-dropping.

It was the private credit and bankers, however, who are becoming noticeably pickier about which data centres to finance – especially if not backed by a hyper-scaler or near the grid for swift interconnection.

AI is likely to become a macroeconomic driver that influences labour markets. One of the smartest investors I know was worried that AI exacerbates the gap between GDP (boosted by infrastructure spending) and employment (which lags).

Given the US Federal Reserve’s dual mandate, they fret that the Fed may keep rates too low to support employment, which in turn risks medium term inflation and steeper yield curves. As with many conversations this week, gold was one way investors discussed trading this risk.

We also debated the implications of the AI boom puncturing. While the size of the capex boom is huge, the impact on GDP is lower than the Davos chatter sometimes suggests. The increase is roughly 1% of GDP, according to BIS – comparable to the US shale boom of the mid-2010s and half as large as the rise in IT investment during the dot-com era. The commercial property and mining investment booms experienced in Japan and Australia during the 1980s and 2010s were over five times as large relative to GDP.

The base case outcome looks well underpinned for this year. But the challenge is that the AI tails could be fat and feedback loops strong. On one hand, a sharp pullback in AI spending could hit GDP and could lead to credit losses. On the other, the hyper-positive outcome also could lead to a much sharper increase in unemployment and weigh on consumer spending. No one really knows how fat the tails are, both right or left, but I got a sense that greater prudence to avoid concentrations by financiers was a recurring theme among leaders.

3. Rethinking diversification

Faced with deep uncertainty on the market paradigm, the desire to diversify was strong. Amongst hedge funds, gold, silver, platinum and copper were high up conviction lists. “Quiet quitting” of US assets, as Katie Koch of TCW put it, was discussed. But strategic asset allocation shifts take time.

Risk appetite remains, but time horizons have shortened. Managers of several large asset pools I met were keen to free up liquidity to retain flexibility. So it was striking at one private breakfast how frank the exchange was between some large asset owners who were frustrated by the lack of distributions from large private-equity portfolios. I suspect this adds ever more pressure to find solutions via secondary and continuation vehicles if exits don’t accelerate.

'Beware complacency' was a theme of investor meetings. Scenarios once considered fringe – protracted tariff regimes, selective decoupling of technology ecosystems, episodic energy bottlenecks – are now being explored.

This all said, the huge structural advantage of US markets was on display. Despite the geopolitical headlines taking centre stage, US equity and bond volatility has remained muted: US bond volatility, as measured by MOVE, is at five-year lows. Meanwhile cyclical sectors – industrial, materials, energy, small caps – have rallied signaling markets pricing firmer US growth.

On the other hand, the gapping out of Japanese long-term bonds tells a different story. Investors appear to be becoming uncomfortable with current levels of government spending in some markets, raising the risk of buyers’ strikes in major fixed income markets. This matters, given the desire to stump up huge sums to increase economic resilience. It also points to a period of financial repression (for example the UK’s flurry of taxes) and reinforces why the base case is de-risking rather than decoupling.

The scale of capital demand from data centres, energy and infrastructure is also reshaping markets. Some expect this to require higher term premia and wider credit spreads – even if, so far this year, markets have moved the other way.

Investors are also rethinking what makes a diversified credit portfolio, asking why they should put 100% of fixed income investment into public assets. In private credit, the pivot toward asset-based lending continues in the US and is spreading to Europe. Some were defensive that the notable credit events of Q4 were largely bank-led deals, but there was also a frank conversation that the locus of likely credit problems was the 2020-21 vintage – when companies set balance sheets when rates were near zero. There is likely more pain to take on some of these. While the conversation was framed around vintages, I can’t help feeling as the asset class has scaled, it’s back to basics about who is a good underwriter of risk and who isn’t.

A historic moment, but which one?

We were all asked which period in the history of markets most resembles today's.

Some thought today rhymed with 1998 – bumpy, getting later in the cycle but still strong returns. Others saw parallels with the early 1970s, when the end of the gold standard created a profound regime change with numerous unintended consequences.

Another reached further back, to the great railway booms of the 19th century, when transformative technology rewarded society more reliably than investors. When I bumped into historian Niall Ferguson, he suggested the presidencies of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. The breadth of analogies underscored the disorientation.

Where next?

Davos is so often a contrarian indicator – as many large conferences are – because they expose what’s already embedded in market expectations, rather than the surprises ahead. This year, fears of the end of globalization look overstated.

The investor Daniel Loeb once wrote that “in order to be a really good investor, you need to be a little bit of a philosopher as well.” The remark felt apt in Davos this year. In a world of shifting regimes, a philosophical mindset – disciplined about risk, sceptical of easy narratives and clear-eyed about what can and cannot be controlled – may be the most useful lesson to take home from the Alps.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Spencer Feingold

March 11, 2026