How to adapt cardiovascular and kidney care in a changing climate

In a warming climate, there is a need to escalate global health adaptation efforts. Image: REUTERS/Ralph Orlowski

- Rising temperatures amplify disease, strain healthcare systems and deepen global inequalities.

- Alongside mitigation strategies, there is a need to escalate global health adaptation efforts, especially in disproportionately affected communities.

- Cardiovascular and kidney diseases are exacerbated by climate change. How can we tackle this challenge and improve the resilience of the health system as a whole?

Climate change is no longer a distant environmental issue – it’s a destabilizing force reshaping the foundations of human health. As rising temperatures amplify disease, strain healthcare systems and deepen global inequalities, understanding this convergence is essential.

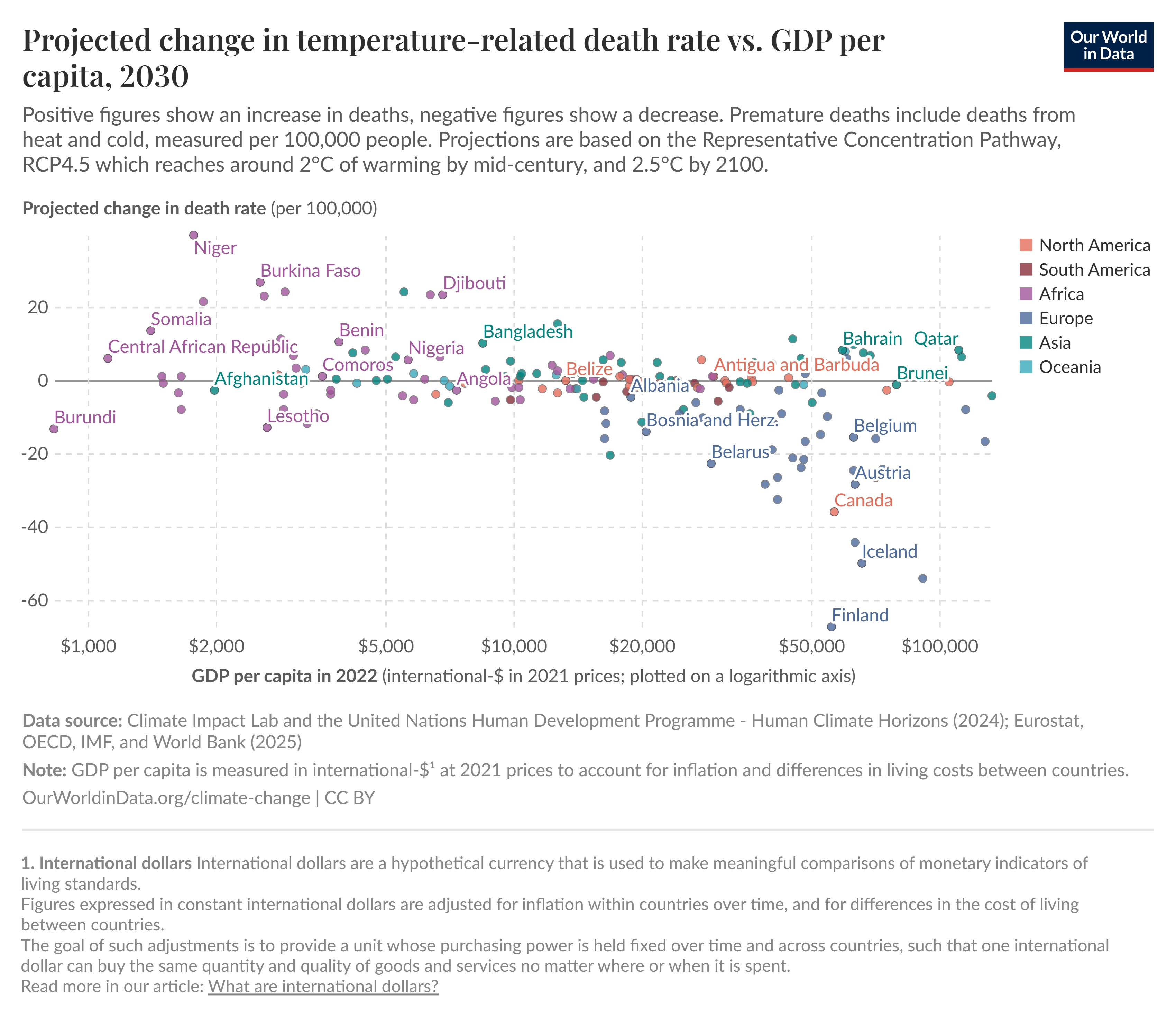

Alongside mitigation strategies, there is a need to escalate global health adaptation efforts, especially in disproportionately affected communities. In a warmer world, many homes across northern Europe, Canada and the US will become unlivable without air conditioning. There will be unpredictable violent storms that damage essential healthcare infrastructure, and soaring energy and grocery bills will push more people into poverty.

By 2050, climate change could contribute to 14.5 million additional deaths, $12.5 trillion in economic losses and $1.1 trillion in extra healthcare costs. Health adaptation makes the conversation about climate change real, urgent and operational in the here and now.

Let’s take cardiovascular and kidney disease as examples. Cardiovascular diseases already cause 32% of global deaths or 17.9 million deaths per year and affect 640 million people around the world. Chronic kidney disease, closely connected to cardiovascular conditions, affects 700 million people or 9% of the global population.

Climate change and other environmental factors play a major role in exacerbating cardiovascular and kidney diseases, through exposure to extreme heat, poor air quality and disruption to health facilities during severe weather events, for example. This in turn increases incidence, prevalence, death and morbidity of cardiovascular and kidney disease, as well as delaying or obstructing access to appropriate care.

Climate-exacerbated diseases like cardiovascular and kidney diseases need to be tackled holistically across sectors to improve the overall resilience of the health system. For businesses operating within the health sector, this means increasing engagement in collaborative programmes and partnerships in affected communities to safeguard and improve equitable access to healthcare in a changing climate.

How can this be best achieved? To help answer this question, the Economist Impact has published a 2030 vision and framework with five components designed to support health systems to minimize the effects of climate change on cardiovascular, kidney and metabolic health.

The first component involves improving the standard of care for people at risk of cardiovascular and kidney diseases, from prevention to early detection and appropriate interventions. Incorporating climate adaptation strategies in this context means considering which groups of individuals might be most at risk from adverse environmental conditions such as extreme heat and air pollution.

Successful models of prevention must now extend beyond individual metabolic risk factors addressed within the walls of the health clinic, towards policies and practices that regulate safe living and working conditions. People living with cardiovascular disease should be advised to increase fluid intake, remain in a cool place and reduce normal activity levels during heat waves. Medication doses may require adjustments too (often an empirical clinical judgement).

The second component involves enhancing healthcare delivery. This includes proactively addressing existing weaknesses in the health system that perpetuate health inequities. This is critical given that climate change will worsen such disparities. Care delivery must be decentralized, for example, through the use of telemedicine services to provide better continuity and equitable access. Health systems will need to prepare for climate disasters through strengthened infrastructure, disaster management planning and emergency protocols for cardiovascular and kidney conditions.

The third component – “greening” health systems – is closely connected with the delivery of good quality care to improve the chances of better health outcomes and decrease the need for associated hospital or clinic visits and resource-intensive end-stage treatments such as dialysis. Alongside population health programmes to improve the screening and detection of disease, precision medicine through genetic testing or AI algorithms will ensure that those patients benefiting from a particular treatment can access it.

Technologies can also support self-management, enabling individuals to better assess their symptoms and receive tailored guidance on next steps. In addition, companies supplying health products and services can integrate the principles of circular design and sustainability early in the discovery, development and marketing lifecycle – alongside expediting decarbonization across the business value chain.

The fourth component – raising awareness and education – is a topic to which health industry leaders can contribute with substantial impact. People living with chronic cardiovascular and kidney conditions may not be aware of the dangers of extreme heat exposure. In addition, one survey of 1,000 healthcare professionals found that fewer than half possessed knowledge about the impact of climate change on kidney health or the environmental impact of kidney care.

Targeted education programmes for health professionals are already underway, integrating climate and health into undergraduate and post-graduate curricula. Collaborations with public health bodies, scientific societies and patient organizations will ensure that good quality information reaches the general public.

The fifth and final component focuses on improving research, data and monitoring. Advancing the climate and health research field at pace will mean strong cross-functional and cross-border collaborations and coordination. From a lack of evidence-based guidelines and policies that protect people living with cardiovascular and kidney disease to understanding underlying pathophysiological and pharmacological mechanisms associated with heat exposures, the evidence gaps are substantial.

Data-driven early warning systems must provide information that is relevant to people living with cardiovascular and kidney diseases. This means listening and learning from local communities. Examples of effective heat warning systems as cardiovascular prevention strategies have already been published.

All five of these components are underpinned by three cross-cutting enablers: multi-sectoral collaboration, financing and leadership. The ambitious vision outlined can be executed in the short-to-medium term and life science companies can act as critical enablers. As climate extremes intensify the risks faced by people with cardiovascular and kidney diseases, strengthening resilient health systems is no longer optional; it is urgent. We must act now to safeguard care, protect people with vulnerabilities and ensure that access to healthcare is inclusive and equitable in a rapidly changing world.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Climate and Health

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Ruma Bhargava and Megha Bhargava

March 6, 2026