More than 'a big beautiful piece of ice': 4 things to know about Greenland

Greenland has become a focal point for geopolitics, climate and science. Image: REUTERS/Marko Djurica

- Greenland, the 'world's largest island', has become a geopolitical focal point and headline news.

- Its ice sheet, mineral wealth and strategic location place it at the intersection of climate science, resource development and territorial governance.

- From rare earth elements to carbon-sequestering seaweed, Greenland’s natural capital demands partnerships that balance economic opportunity with environmental stewardship.

The “big, beautiful piece of ice” continues to dominate the news cycle. US President Donald Trump agreed in Davos last week to a "framework of a future deal" following tensions with European leaders over Greenland’s future.

Other recent headlines include US musician Neil Young offering Greenlanders free access to his back catalogue, and new research suggesting that a native species of seaweed around the island could deliver outsized carbon‑sequestration benefits.

Together, these very different developments underline how the "world’s largest island" has become a focal point not only for geopolitics, but for climate, culture and science.

Greenland at a glance

Geologically part of North America but politically an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, the island is located across Baffin Bay from the Canadian Arctic.

Its scale is vast. Greenland is roughly three times the size of Texas, with 80% of its landmass buried under permanent ice and temperatures rarely above freezing.

The inaccessible interior restricts the population to a thin, rocky coastal strip where glacial erosion has left the soil "water repellent" and the land unsuitable for agriculture and most land mammals. The island, therefore, relies on imports for most essential goods, driving up the cost of living.

Classified as an 'Arctic Desert', it is a place defined by extremes: parts of its far north receive less annual precipitation than the Sahara, qualifying them as true polar deserts, yet the island is frequently battered by 'piteraq' storms that bring extreme hurricane-speed winds.

Four structural factors shaping Greenland's global role

1. It is a global climate archive

Before geopolitical interest surged, Greenland was – and remains – indispensable to climate science. The ice sheet is not just a frozen reservoir; it is a historical record.

By drilling 'ice cores' deep into the sheet, scientists can reconstruct the Earth’s climate history over hundreds of thousands of years. These cores provide the baseline data for understanding how atmospheric carbon correlates with global temperature rise.

This archive is also rewriting history. A 2023 study in the journal Science revealed that the island was actually ice-free and vegetated as recently as 416,000 years ago, not millions of years ago as long thought. A follow-up study corroborated this, finding evidence of "seeds, twigs and insect parts" two miles under the ice, indicating the ice sheet is far more fragile than models once assumed.

2. A weakening 'Albedo' shield

Greenland functions as a planetary cooling mechanism through the 'Albedo effect' – the ability of white ice to reflect solar radiation back into space.

As global temperatures rise, the bright white snow melts into darker blue water or exposes grey rock. Darker surfaces absorb rather than reflect heat, creating a feedback loop that accelerates local warming.

Research indicates this process is a primary driver of 'Arctic Amplification', where the Arctic warms significantly faster than the rest of the planet. This thermal shift disrupts weather patterns well beyond the Arctic Circle, influencing heatwaves and jet stream stability across North America and Europe.

3. Mass ice loss as systemic economic risk

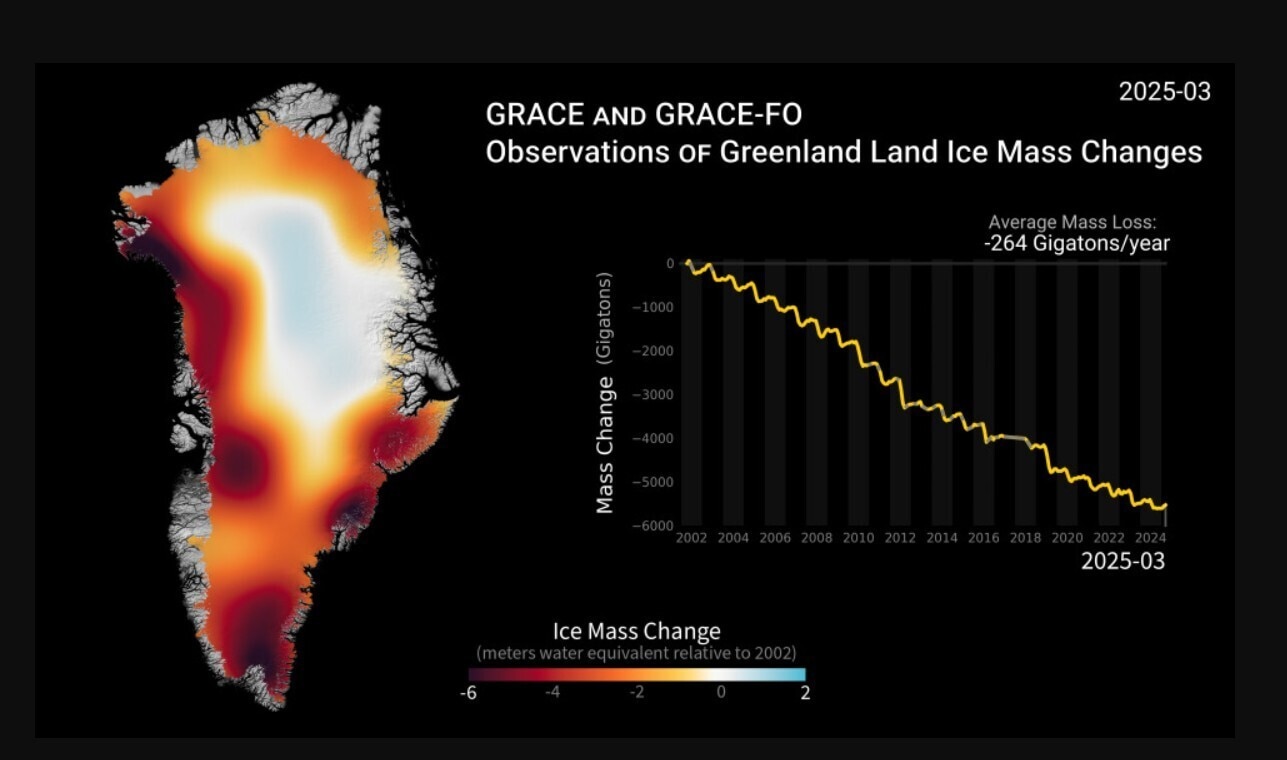

Covering almost 1.7 million square kilometres, the stability of Greenland's ice sheet is a central metric for global risk. Today, Greenland is losing ice at a sustained rate, with recent melt seasons continuing a multi‑decade trend of net mass loss.

Recent assessments of the 2024-2025 melt seasons show persistent, high‑volume mass loss from the ice sheet. In total, Greenland holds enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by more than seven metres if it were to melt entirely. Even on much smaller scales, incremental melt is already contributing measurably to observed sea‑level rise.

Warming does not simply “open up” the Arctic. As outlet glaciers accelerate and retreat, they can calve more icebergs into fjords and shipping lanes, while surface meltwater and changing sea‑ice conditions complicate navigation. For vessels, ports and coastal communities, the result is a paradox: shorter‑term gains in seasonal access coupled with higher operational risk and more volatile coastal environments.

For insurers, urban planners and sovereign debt analysts, the rate of Greenland’s melt has become a material risk variable. It shapes flood probabilities for coastal infrastructure, alters long‑term valuations of ports and industrial zones, and feeds into stress‑testing of global supply chains that depend on low‑lying hubs from Rotterdam to Shenzhen.

4. Mineral potential vs environmental limits

Greenland holds significant reserves of rare earth elements, commonly used in electric vehicle motors, wind turbines and semiconductors.

In 2021, Inatsisartut (Greenland Parliament) passed Act No. 20 banning uranium prospecting, exploration and extraction where the content exceeds 100ppm (parts per million). All projects require environmental impact assessments through the Mineral Resources Authority.

There is also a legacy aspect to consider. Thawing ice is projected to expose Camp Century, a decommissioned 1960s US base containing chemical and radioactive waste. This raises questions about remediation and environmental liability under current ice/melt conditions.

The renewed focus on Greenland signals a shift in global priorities. Once seen as remote ice or a defence outpost, the island now connects climate science with resource economics.

This reality mirrors the Forum’s Global Risks Report 2026, which notes that while geoeconomic confrontation dominates the short-term agenda, “critical change to Earth systems” remains a top-tier threat over the next decade.

The Centre for Nature and Climate emphasizes that Greenland’s trajectory will determine our ability to operate within “planetary boundaries”, defining not just the future of the Arctic but the resilience of the global economy itself.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Geo-Economics and PoliticsSee all

Ariel Kastner, Miriam Schive and Sofia Balestrin

January 29, 2026