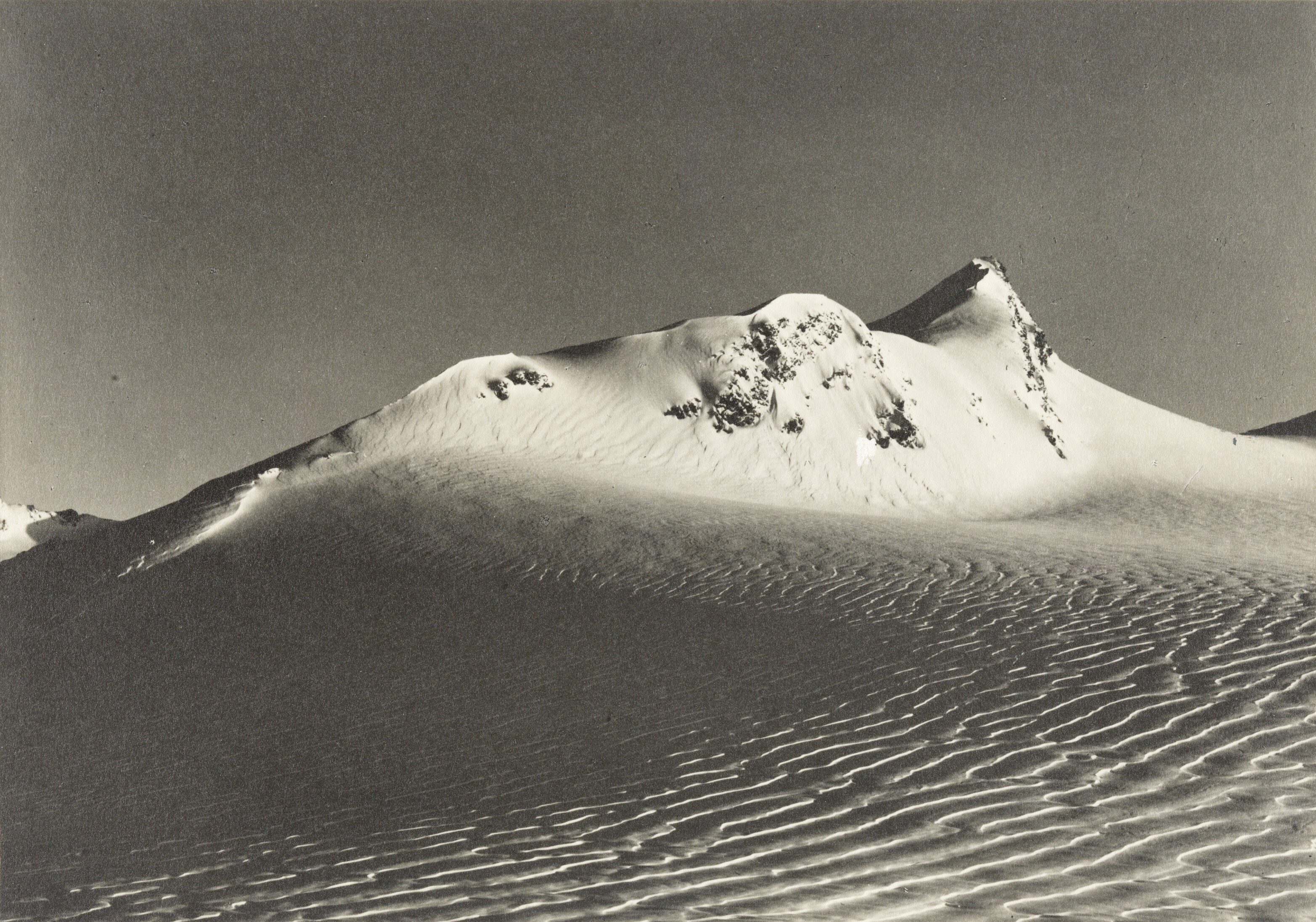

What's so 'Magic Mountain' about the Annual Meeting in Davos

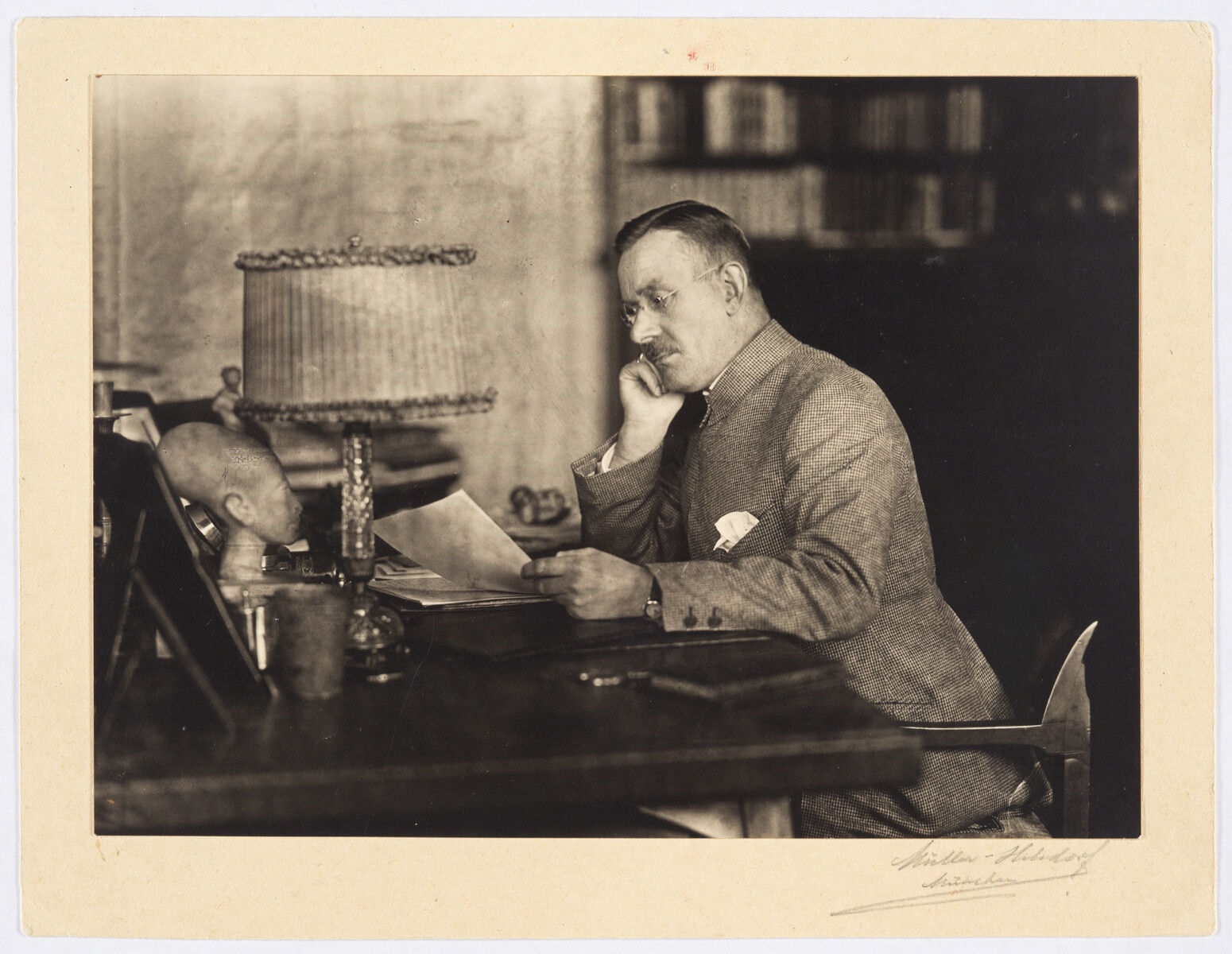

What could a century-old novel like Magic Mountain possibly have to say about the current state of the world? Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Thomas Mann Archiv

- The title of Thomas Mann's 101-year-old novel The Magic Mountain is still used as shorthand for the World Economic Forum’s yearly confab.

- They share more than a setting in Davos; the tension between a collective drive to modernize and related anxieties at the heart of the book endures.

- That tension will be threaded throughout the Forum’s Annual Meeting later this month.

It started with a cold, and some bad medical advice. And a stark realization that disengaging from the world is maybe not the best way to deal with its flaws.

One War to End All Wars and about 1,000 pages later, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain took shape as a monumental novel its author described as “odd entertainment.” Readers have been undeterred. More than a century after its publication, the anxieties about the future gripping patients who refuse to leave its fictional Alpine sanatorium still seem very familiar.

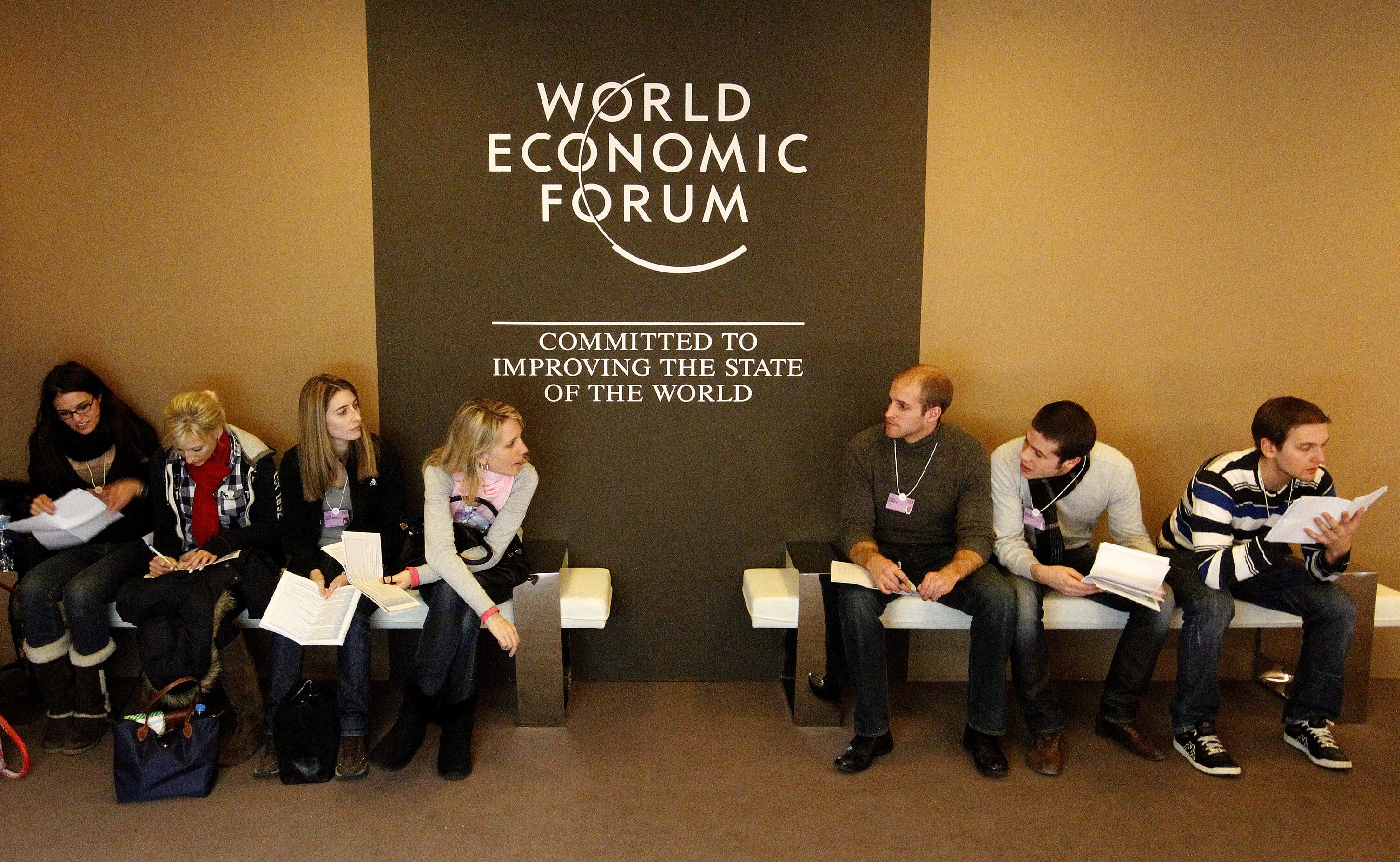

The clinic that inspired Mann’s made-up version was a 10-minute walk (longer if navigating icy sidewalks in shoe grips) from the Davos Congress Centre. Heads of state, executives, people running global non-profits and big thinkers with popular podcasts will converge there soon. But also a lot of other people you’ve likely never heard of, “genuinely trying to work out how to make a more equitable world,” as the artist Trevor Paglen put it after attending an Annual Meeting several years ago. A different cast of characters, roughly the same dividing line that animates The Magic Mountain.

On one side, proponents of the power of science, reason and global cooperation to solve big problems. In Mann’s day, that meant things like tuberculosis and expansionism. In 2026, it might mean a warming climate and… expansionism.

On the other side, the “instinct-worshippers." Big believers in the raw power of markets, and that might can make right. Build economies for the now, don’t make assumptions about arrangements necessary for the future, especially if you’re not getting the best of those deals.

Leaders of both camps will make appearances at the Congress Centre. In panel discussions and interviews and over drinks, other participants will pick apart the merits of each. Like Hans, the impressionable protagonist of The Magic Mountain, some won’t exactly be sure which is right. Hans “took stock” of both, in a way that a century later would probably take form as one of the many “reflecting on” LinkedIn posts that follow Annual Meetings.

Have you read?

The stakes are much higher than social media views. The general outlines of the global economy will be drawn by people leaning in the direction of one camp or the other. What kind of growth is best, after all?

For Settembrini, a Magic Mountain character representing the science-and-reason camp, it’s growth guided by embracing change. He’s an editor working for a globalist organization (yikes!) and can come off as condescending, even if he means well.

If he was participating in an Annual Meeting panel on Europe’s current, very complicated energy situation, Settembrini might argue for full-speed-ahead on new solar and wind infrastructure – even if the economics don’t always work for everyone quite yet. We’re in another classical age, embrace it.

His opposition is the character Naphta, a fictional reminder that there will always be people eager to put Earth back at the centre of the solar system. Gratification first, intellect second. “Society doesn’t know what it wants,” Naphta says. “It shouts for a campaign against the fall in the birthrate, it demands a reduction in the cost of bringing up children,” but what it really needs “is Terror.” He doesn’t get invited to many dinner parties.

Still, he’s hard to ignore. He’s a good talker, and his warnings about self-defeating foolishness dressed up in “intellectual garb” land with Hans. If he was participating in a panel on Europe’s current energy situation, Naphta might argue against going green when there are so many fossil fuels yet to be burned.

Naphta dismisses Settembrini and his colleagues as elitists backed by shadowy, powerful forces. But the elitists don’t really seem to be trying to conceal what they’re up to. In fact, they won’t shut up about it. Settembrini “was almost too expansive,” Hans complains, after hearing all about the globalist society’s many grand lodges and high-profile participants from Voltaire to George Washington.

Hans and his fellow residents at the Berghof sanatorium are aware of the geopolitical storm clouds forming over “the flatland” below. They discuss the fates of places like the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the same way meeting participants may soon be parsing the what-ifs of places like Venezuela and Ukraine.

But the residents can’t bring themselves to leave. That is, until talking through the issues of the day at a safe remove is suddenly no longer an option, and the issues come for them – in the form of World War I.

The story’s characters try to avoid the messiness of the world below. At its best, the Annual Meeting is a place to confront the mess. The Magic Mountain can make for good reading in a plane or train headed to Davos.

Some advice: feel free to skip parts and don’t take it too seriously. The shortest summary is that it’s about time, and how we choose to make good use of it.

And how sometimes we don’t.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Global CooperationSee all

Simon O'Connell

February 20, 2026