Beyond obesity: what is metabolic health and why does it matter?

The obesity epidemic is, at its core, a crisis of metabolic health. Image: REUTERS/Andrew Silver

Robert Lustig

Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)- Our metabolic health is shaped by nearly every aspect of daily life and a confluence of multiple industries and sectors, leaving no one truly accountable for the state we are in today.

- Whilst we are facing the obesity epidemic, at the heart of this issue is poor population metabolic health, affecting millions of people of normal weight who are still significantly at risk.

- Change is possible. With strong government guardrails, a realignment of incentives and a joint commitment across industries, we can tackle metabolic health.

Breakthroughs in science, politics and media coverage of celebrities have finally made the world pay attention to obesity – one of the most significant societal and public health challenges of our time.

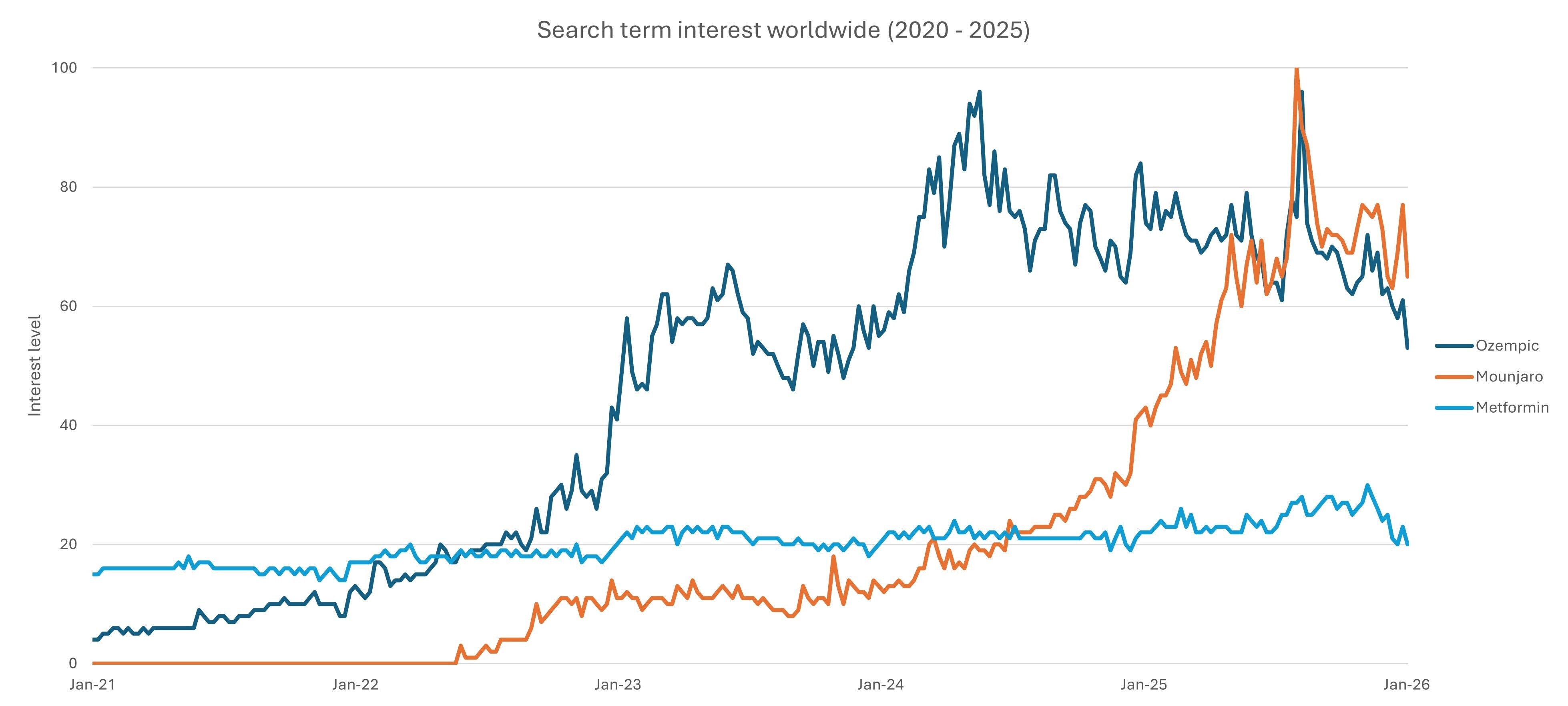

Today, more than 1 billion people live with obesity, a condition associated with almost 200 diseases. Scientific advances have produced one of the most promising medicines in decades: GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1) analogue medications, such as Ozempic and Mounjaro, which have documented benefits for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, among other conditions. These medications have demonstrated that obesity is not simply a result of bad behaviour or lack of willpower, but rather that weight is influenced by biochemistry.

Yet, while GLP-1s represent an important addition to the obesity toolbox, they themselves cannot fix the much more pressing medical, economic and social challenge we face: poor global metabolic health.

Obesity is a biomarker, not the root cause. Is it the right target?

Behind the headlines and pharmaceutical breakthroughs lies a deeper, more urgent problem. We are not only facing an obesity epidemic, but a metabolic health crisis, one that silently affects millions who are of normal weight but are nonetheless significantly at risk.

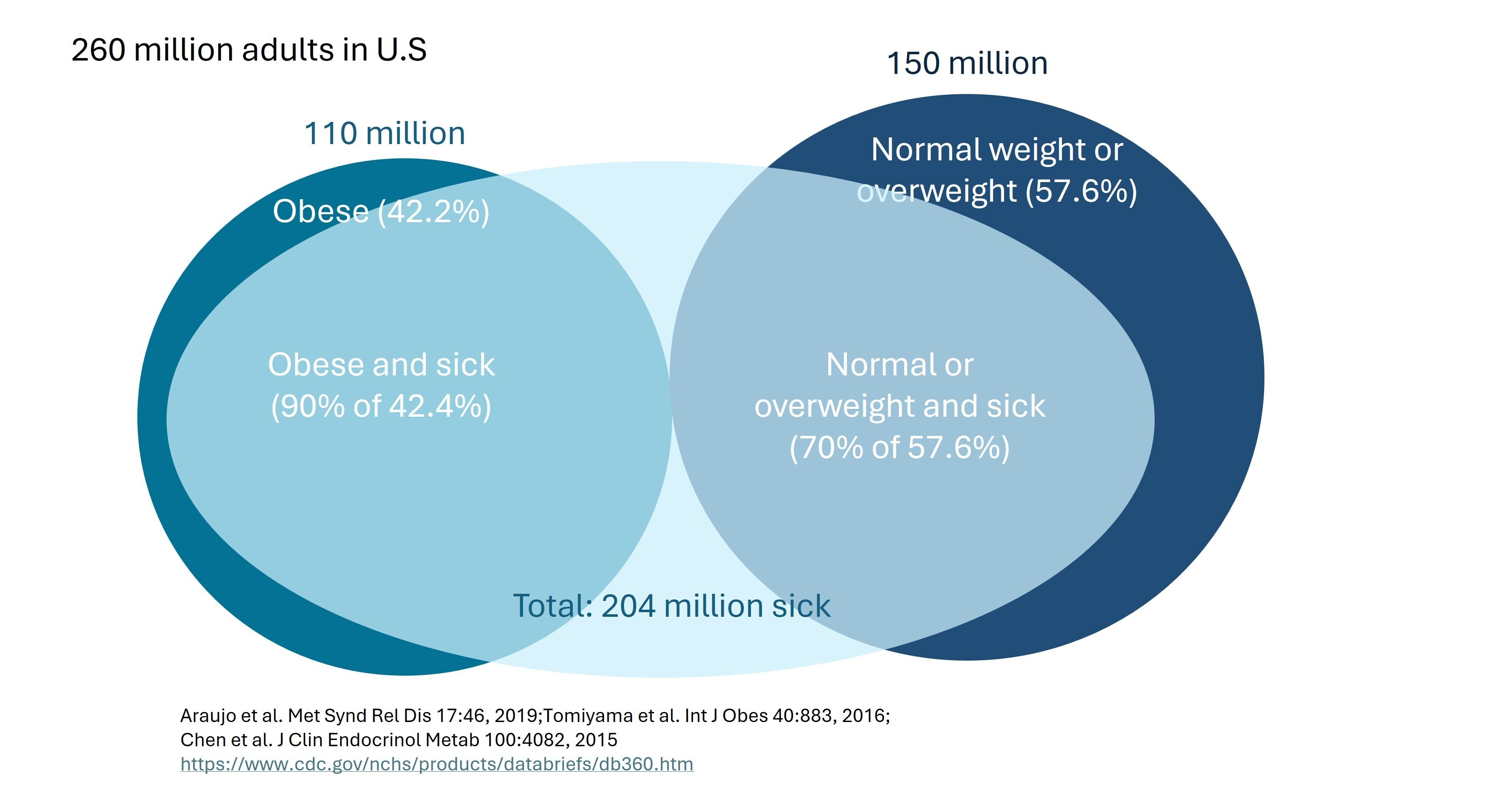

Obesity is a biomarker – it’s one example of a visible outcome of metabolic dysfunction. Focusing solely on obesity obscures the true challenge, as we ignore large segments of the population that are within the normal BMI range but are metabolically unhealthy. More than 40% of US adults are within the normal BMI range but are still metabolically ill, for example.

Our metabolic health is shaped by a range of indicators, including blood glucose, body composition, blood pressure and lipid levels. Any alteration in these biomarkers may harbinger chronic inflammation and insulin resistance, which are the true drivers of cardiovascular disease, cancer, cognitive decline, infertility, fatty liver and more. Metabolic health is the problem; obesity is just one marker.

Inclusive view of obesity and metabolic dysfunction

Focusing efforts solely on those who are obese misses a large subset of the population with poor metabolic health. Poor metabolic health does not always present as excess body weight. There are three types of fat depots:

- Subcutaneous fat (most visible): Fat stored beneath the skin (hips, thighs, arms). People with higher levels may appear overweight or obese.

- Visceral fat: fat accumulated between internal organs (for example, intestines). Visceral fat is linked to insulin resistance, inflammation, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

- Ectopic fat (least visible): fat stored in locations not classically expected for fat storage (such as liver muscles, heart). Can accumulate without weight gain. Associated with type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke and dementia.

High levels of visceral and ectopic fat are most concerning to our health, but often less visible. A focus solely on obesity, therefore, ignores these at-risk individuals.

Death by a thousand cuts – the accumulation of systemic failures

Metabolic health is shaped by nearly every aspect of daily life: diet, physical activity, environmental exposures, stress and sleep. These factors are controlled and influenced by multiple sectors. The diverse range of contributors and the complexity of causal factors have resulted in weak accountability across industries, with responsibility largely falling on individuals. The economic burden has become too significant to ignore. Chronic metabolic diseases are pushing healthcare costs to unsustainable levels.

The reason for this is clear: it is a result of decades of misaligned incentives. For example, hospitals and pharma companies are reimbursed for treating illness, not preventing it. Food companies are rewarded for sales volumes, not nutritional quality. Some governments continue to subsidize – at a significant scale – crops that produce products that cause insulin resistance. Innovation flows toward what the system rewards. The question is: how can food and health systems transform to incentivize and reward metabolic health?

The time is now

Growing public awareness and consumer interest around the Western diet have brought unprecedented attention, creating a surge of curiosity, energy and demand for new solutions. Signals of momentum include (but are not limited to):

- Intensifying government pressure: the MAHA movement (Make America Healthy Again) and increased scrutiny around ultra-processed foods, including the city of San Francisco’s lawsuit against 10 UPF companies, raise the urgent need for change across the food system.

- Improved consumer awareness: people have greater access to nutritional data and personal health biomarkers. Consumer apps, such as Yuka, Perfact or FoodHealth, make it easier to assess product quality, often at the moment of consumer choice or purchase.

- A booming wellness economy: valued at $6.8 trillion, the wellness industry now outpaces global industries such as sports ($2.7 trillion), tourism ($5 trillion) and the green economy ($5.1 trillion). Wearables and digital platforms enable personalized diet and lifestyle recommendations, real-time biomarker tracking and behavioural nudges that enable healthier choices. At the same time, entire consumer industries are redesigning their strategies to cater for populations taking GLP-1s.

Empowering each sector to shape positive change

A person’s health is shaped long before they enter a clinic. From food systems to technology, pharmaceuticals to insurance and urban design, multiple industries influence metabolic health – yet few are incentivized to improve it. Emerging examples show how coordinated action and aligned incentives can create measurable impact:

1. Raising industry standards and reformulating at scale

The UK’s salt-reduction programme brought together food industry actors to collectively reduce levels of salt across entire product categories. As a result, the UK achieved measurable reductions in blood pressure and hypertension risk across the population. This coordinated approach levelled the playing field for companies and demonstrated the power of shared standards and improved population health outcomes.

2. Product re-engineering with metabolic health as the goal

Select food companies have been re-engineering and improving the health impact of their product portfolios, sometimes openly marketing the changes; other times, quietly making progress. Stealth approaches can be particularly effective, avoiding customer bias as consumers often associate healthier products with poorer taste, leading to reduced demand.

3. Data-driven integrated and intelligent care models

Advanced health systems, such as Abu Dhabi’s intelligent health system, demonstrate the power of linking clinical, insurance, genomic, environmental and lifestyle data into a fully sovereign, privacy-protected system. This enables population-level trend analysis, predictive care strategies and targeted preventive health interventions (including the development of a cross-sector Healthy Living Strategy), effectively moving healthcare upstream.

4. Agricultural practices for better health and nutritional quality

There is a direct link between soil health and metabolic health. Growing produce in soil (rather than dirt) results in greater soil microbiome and resultant nutritional quality – dirt is dead, soil is alive. Efforts to promote regenerative agriculture will pay for themselves in quality and yield, while reducing environmental costs.

Together, these cases illustrate that aligned incentives, strong regulatory guardrails, fair competition and targeted incentives can unlock meaningful progress. When no single organization is left at a disadvantage, innovation flows toward better metabolic health outcomes.

Looking ahead

Each of us can play a role in tackling this multi-sectoral challenge of metabolic health. Our institutions, our employers, our communities and ourselves are all stakeholders. Achieving significant progress requires strong regulatory guardrails, bold private sector innovation and informed and empowered consumers.

Change is coming, that is certain. What is not certain is the venue, the timeline or who the adopters and dinosaurs will be.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Mental Health

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Ruma Bhargava and Megha Bhargava

March 6, 2026