The sports economy: What is it and how could it improve the health of both people and planet?

From local parks to global stages, grassroots sport is essential for fostering healthy, active societies and sports economy. .

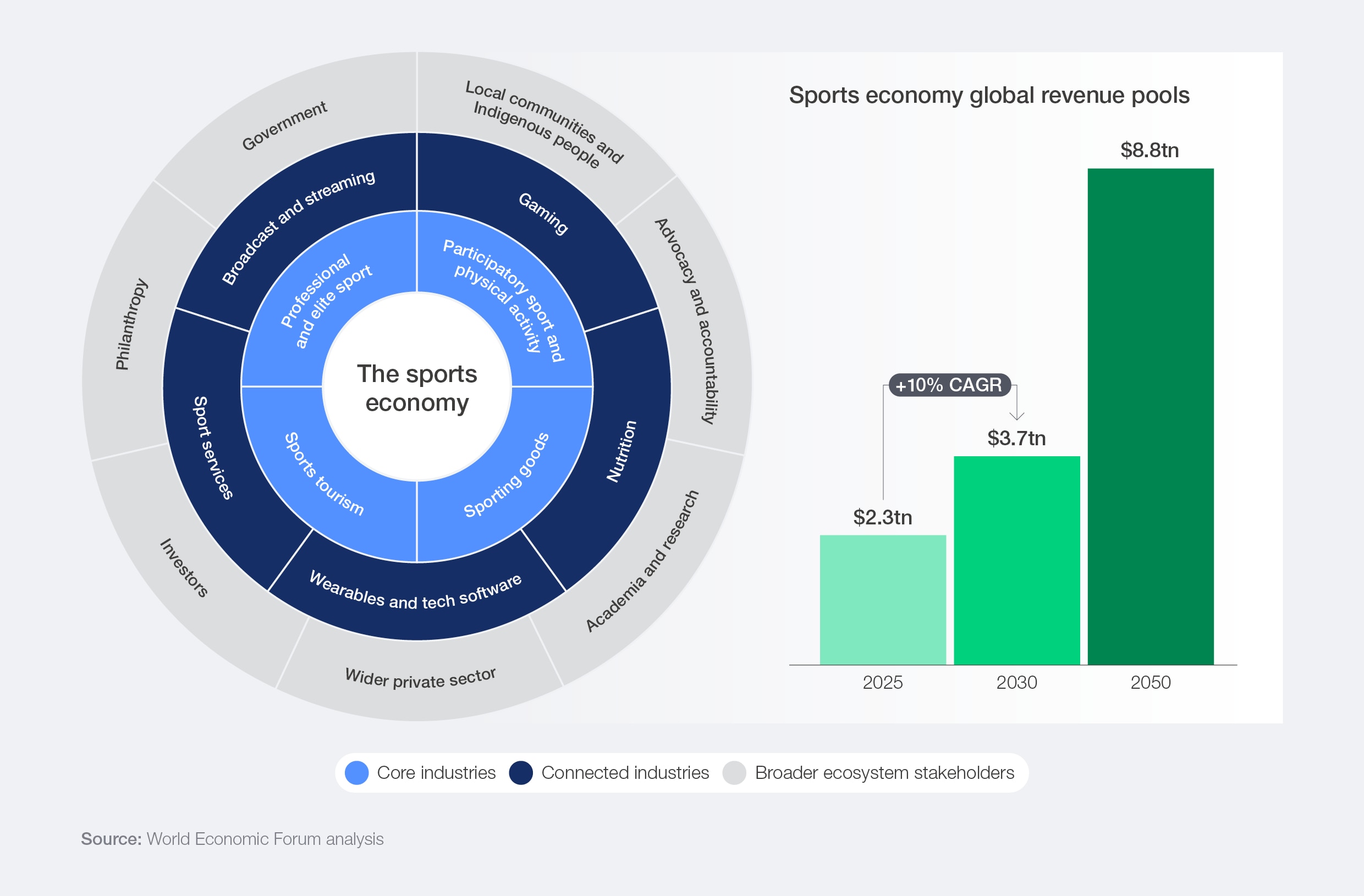

- The sports economy is worth $2.3 trillion a year but faces challenges from climate change and physical inactivity.

- With the sector projected to reach $8.8 trillion by 2050, a new World Economic Forum report outlines three pathways to ensure resilience.

- Through multistakeholder partnerships and coordinated action, the global sports economy can be a catalyst to redefine global prosperity, encompassing not only financial returns, but also healthier societies and thriving natural ecosystems.

When you think about sport, what do you picture? The FIFA World Cup or grassroots games played by children in your local park?

Both are equally part of the $2.3 trillion sports economy, a new Forum report shows. This vast sector ranges from global events and consumer brands, to adventure tourism and active lifestyles – creating jobs, driving growth and supporting healthier lives.

In an increasingly divided world, sport is one of the few uniting forces – but today it faces an unprecedented challenge from climate change.

Extreme weather disrupted more than 2,000 global events between 2004 and 2024, according to a study in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, with a fifth of those being sporting events.

At the FIFA Club World Cup in Los Angeles in June 2025, six matches were delayed due to storms.

Planetary health is central to human health and a sustainable sports economy.

In collaboration with Oliver Wyman, the World Economic Forum has published Sports for People and Planet, a report that measures the size of the sports economy – and outlines how to drive resilience by addressing both physical inactivity and the climate and nature crisis.

What is the sports economy?

It is a major global economic driver generating $2.3 trillion in annual revenues, close to 2% of global GDP.

Current projections show the sector, including connected industries such as broadcasting and streaming, nutrition and wearables, growing to $3.7 trillion by 2030 (a 10% compound annual growth rate) and reaching $8.8 trillion by 2050.

The growth of the sports economy is being shaped by four trends:

- The emergence of sports as an asset class.

- The mainstreaming of women's sport – revenues tripled between 2022 and 2025 to $2.35 billion.

- Rebalancing of sports growth with emerging economies.

- The acceleration of sports tourism – the fastest-growing area of tourism.

But it faces two main, interconnected challenges, which it can also help to address:

1. Rising physical inactivity is eroding future demand

In 2024, around one in three adults didn't get the recommended 150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise each week, according to the World Health Organization.

Meanwhile, a 2021 IPSOS survey for the World Economic Forum found that over half of people (58%) want to do more sport, but they're limited by a lack of time, cost, weather and access to facilities.

The report notes: "As fiscal priorities shift towards acute healthcare, defence and crisis response, funding for prevention and community sport initiatives risks further erosion."

2. Climate change is disrupting sports activities

Physical climate risks, including extreme weather events and air and water pollution, are impacting everything from event scheduling and athlete health, to the infrastructure and natural settings of sports.

Meanwhile, essential ecosystem services, such as freshwater resources critical for sporting goods production and sports tourism, are under increasing strain.

1 in 5

UK stadiums affected by fluvial flooding by 2050

10

countries with the enough snow to host the Winter Olympics by 2040

40%

of participants failed to complete the women's marathon at the World Athletic Championships in Qatar

3

US leagues forced to cancel games during the 2023 Canada wildfires

The industry itself is contributing to climate change, emitting up to an estimated 450 million tonnes in emissions each year – more than any European nation except Germany.

These two risks compound on each other. For example, heatwaves, pollution and extreme weather not only disrupt competitions and training for elite athletes, but they also discourage physical activity, and grassroots sport, impacting health and wellbeing at every level.

By 2030, physical inactivity, climate change and nature loss could reduce annual revenues of the sports economy by 14%, potentially increasing up to 18% by 2050.

Sport depends on stable environmental conditions. More than 90% of media rights and 76% of sponsorship revenues in professional sport are linked to outdoor activities, placing its two biggest revenue streams at direct risk from environmental disruption and the loss of visual appeal related to degradation.

But the sports economy cannot solve these challenges alone.

Pathways to prosperity

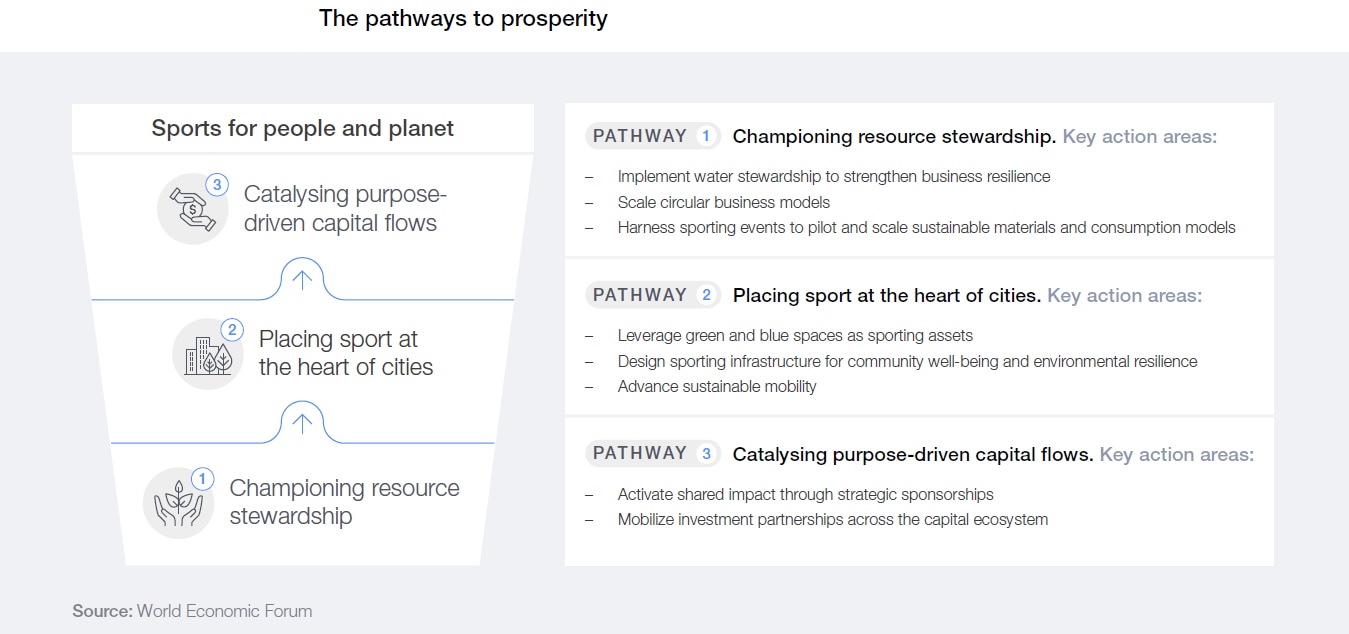

The report identifies three key pathways for the sports economy to advance economic, social and environmental prosperity through multistakeholder partnerships.

There are examples of this already in action, such as the UN's Sports for Climate Action and Sports for Nature frameworks for professional and participatory sporting organizations, which set guidelines and establish reporting standards to catalyze action.

But a more joined-up approach is possible.

The report notes there is now a very real opportunity to "transform systemic risks into drivers of innovation, growth and shared value".

Together, these three distinct pathways form a coordinated transformation funnel, driving change from within the sector outwards:

1. Championing resource stewardship

As of 2025, humans are consuming the Earth's natural resources at 1.8 times the speed at which the Earth can regenerate. The growth of the sports economy can only be achieved within the limits of the planet.

The sector is deeply interconnected with the four principal value chains – food, energy, infrastructure and fashion – that together drive 90% of human-induced pressure on nature and biodiversity loss.

"By championing resource stewardship, the sports economy can turn resource constraints into catalysts for innovation, resilience and inclusive growth," the report says.

By 2030, we face a global shortfall in the freshwater supply of 40%, which will only be further widened by the impacts of the climate crisis. Not only will this affect local communities' access to safe drinking water, but it will also restrict participation in water-based sports and challenge the sporting goods industry’s ability to sustain production.

Between 2019 and 2023, PUMA was able to save more than 2.4 million cubic metres of water per year - around seven million bathtubs - through various efficiency programmes.

Strategic partnerships with sports governing bodies can enhance resource stewardship, as they serve as key stakeholders in efforts to minimize surplus waste generated at competitive events.

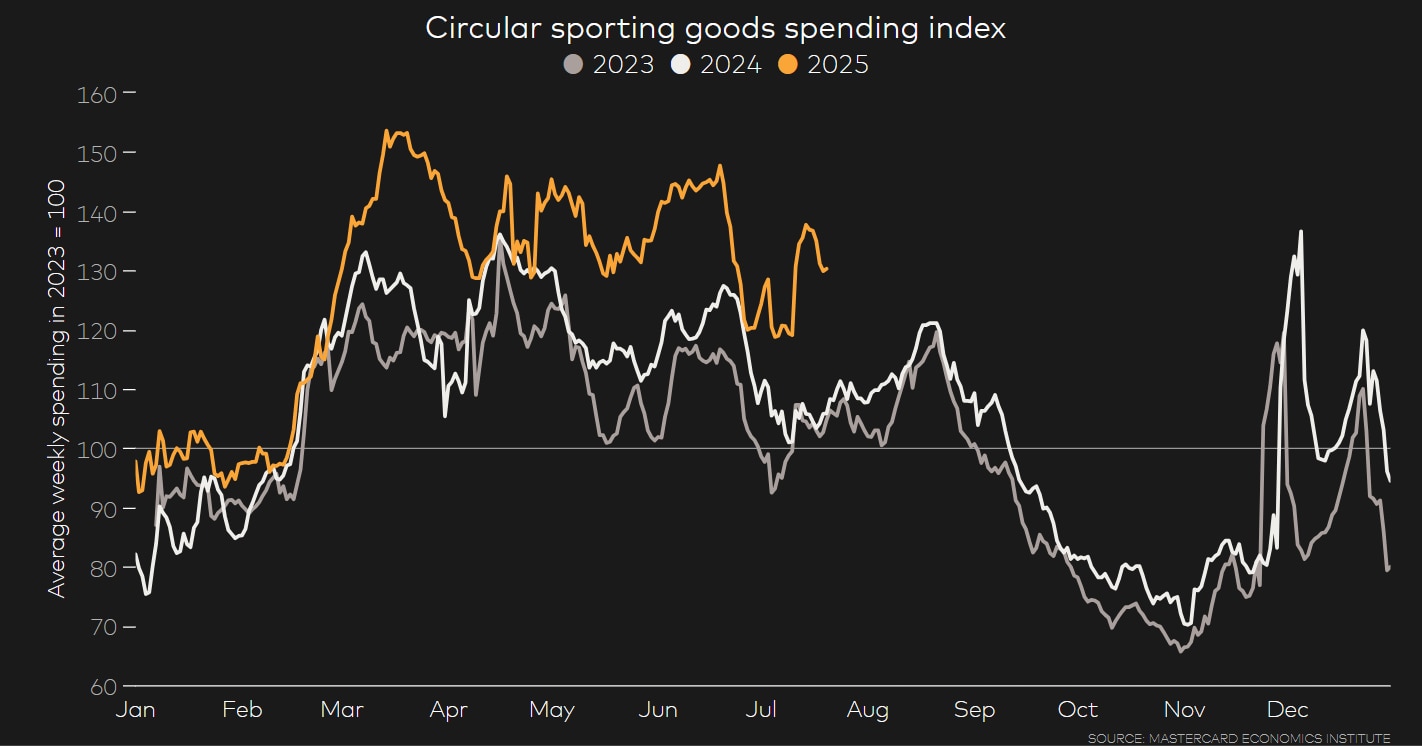

In August 2025, Mastercard found that spending on circular sports is growing year on year, with sales of used sporting equipment now nearly 30% above 2022 levels.

Public policy will be key in supporting this shift, for instance, through tax incentives for goods produced with lower environmental impact.

2. Placing sport at the heart of cities

Our physical environment has a huge impact on shaping our quality of life and longevity. The report finds that around 80% of the factors influencing societal health lie outside the healthcare system.

By 2050, urban areas will be home to nearly 70% of the world’s population meaning their design will be critical to people's wellbeing, and the development of a resilient sports economy.

Bad weather, lack of money and lack of time remain the biggest barriers to physical activity, but cities can address these by ensuring equal access to nature, sustainably built sports infrastructure, and sustainable mobility.

Research in Spain shows a link between access to urban green spaces and higher physical activity levels, while restoring natural habitats can improve air quality.

Paris is a great example of a city marrying sport and nature after it used hosting the 2024 Olympics as a catalyst to clean up the Seine. This summer, the water quality in the Ile-de-France region was declared "exceptional".

Meanwhile, countries such as Viet Nam are rolling out dedicated cycle lanes to cut vehicle emissions and boost activity. In the Netherlands, the Dutch F1 Grand Prix required all 110,000 spectators to arrive either by public transport or bike, with storage space for 45,000 bicycles.

3. Catalyzing purpose-driven capital flows

Purpose-driven investment and corporate sponsorship can help to unlock new avenues for growth, says the report, enabling the sports economy to deliver health, environmental and financial benefits to communities.

In places facing growing climate and nature risks, investors can partner with governments to transform sporting infrastructure into hubs of community resilience.

Stadiums and sports grounds can be designed to withstand the increasing frequency of natural disasters, doing double duty as sporting venues – and community shelters during emergencies.

Community facilities co-funded by government and investors can promote preventative healthcare.

A good example of this is La Liga’s Athletic Club San Mamés Stadium in Bilbao, Spain, built in 2013 and co-funded by the local municipality, Biscay’s Provincial Council and the Basque Government. It includes public swimming pools, a gym and wellness spaces for the local community.

Mutually beneficial partnerships include DHL pairing with F1 to accelerate their adoption of biofuel-powered trucks, more fuel-efficient aircraft and the launch of sustainable motorhomes to house their logistics team during certain phases of the race tour.

Sponsors can also leverage sports partnerships, such as TCS' sponsorship of the London Marathon, to enhance employee wellbeing.

Bold leadership, partnerships and strengthened governance can help the sports economy to reinforce the socio-environmental systems it depends on, boost profitability and participation, and reduce its environmental footprint.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Pooja Chhabria

February 27, 2026