Technology will take our jobs? We've heard that one before

Pianos have been automated for a long time, yet we still want other people to play them. Does the same thing apply to other kinds of work? Image: REUTERS/Aleksandra Szmigiel

- Professions threatened by technology have proven surprisingly resilient throughout history.

- That’s worth recognizing as artificial intelligence assumes more tasks, though this particular story won’t necessarily end well for everyone.

Ramon Novarro was very good at one thing. Or so it seemed.

The first part of the Hollywood actor’s career was spent in silent films as a “sheik type,” a job that mostly required strutting around and being handsome. According to news accounts from the late 1920s, it was also a job threatened by a technological breakthrough: sound. A grating voice or a thick accent could suddenly be a career-ender.

It turned out that Novarro was good at more than one thing. A former singing waiter with some killer pipes, he was able to croon his way into a second part of his career that capitalized on the novelty of “talkies.”

There’s a long history of technology erasing jobs. There’s a story just as old of people successfully manoeuvring through a middle ground to adapt – by leaning into skills that maximize innovation and genuinely add value.

Gigs not always as glamorous as “film star” have proven equally resilient, if not more so. Consider the bank teller, a profession once slated for demise that’s nonetheless persisted. The number of travel agents in the US is expected to increase in the coming decade, even if many Americans haven’t booked their holidays through anything but a website for years. Radiologists have also so far defied expectations for erasure.

And, more than a century after the invention of the automated player piano, people insist on watching and listening to other people perform. The ranks of employed musicians continue to grow.

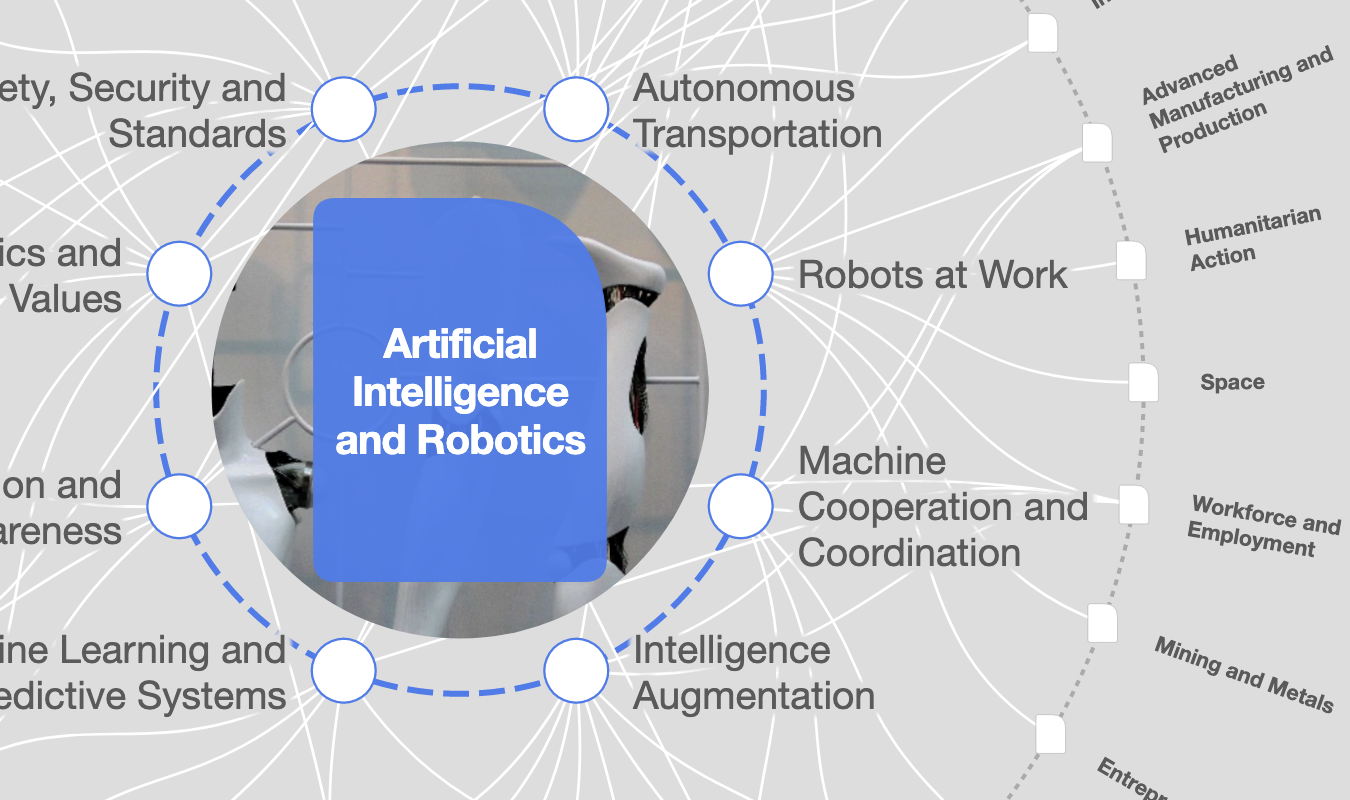

That kind of practical elasticity merits notice, at a time when the discourse on artificial intelligence and work tends to veer in the direction of either wide-eyed optimism or total calamity.

“AI is going to make a lot of music,” Harvey Mason Jr., the CEO of the Recording Academy, said during an interview on the sidelines of Davos last month. But the music that truly resonates, he added, will be created and performed by humans.

“You could take a page from your journal or a diary and give it to AI and say, ‘make a song about this’,” Mason said. “But the question is always going to be, will it translate that or will it convey that the same way that I would as a human, or someone who actually lived it and felt it in my heart, in my bones?”

The human touch may prove just as decisive for other professions. There’s a big caveat, of course.

Technology itself may not have the final say on who stays and goes in different realms of work, because people will dictate what they want from those professions. But not everyone will make the cut.

That’s why even relatively optimistic economists tend to hedge a bit when they discuss what’s coming. Workers will adapt, just not all of them. Or, as Nobel laureate in economics Christopher Pissarides put it during his own interview at Davos, “There's a lot of heterogeneity.”

“In other words, different groups will be hit differently by AI,” Pissarides said. The most sustainable jobs will be those that “require the human ability to feel, to show empathy.” Details on how exactly that will play out within different occupations remain sketchy. History could be instructive.

‘A flood of smoke and flame’

For Ramon Novarro, one skill didn’t cut it anymore just as another became invaluable. He and others in Hollywood managed to adapt to a new technology, and not for the last time.

When television provided a technological means to being entertained at home a few decades later, the film industry blanched. But the impact wasn’t exactly as anticipated; many people still wanted the communal experience of a seemingly redundant movie theatre. There are still more than 12,000 cinemas operating in Europe, employing hundreds of thousands of workers.

People may also want a bank teller who can step out from behind a counter to talk to them about weighty investment decisions. “The bank teller who just took deposits has been eliminated by the money machine,” a US Labor Department official declared a few decades ago. A decade from now, more than 300,000 people are still expected to be employed as tellers in the US.

Some people clearly want more personal guidance on planning a holiday than what’s available on a website, and they may be happy to pay for it – though they may be paying someone who prefers the title travel “advisor” to “agent.” Other people would prefer discussing the unsettling things identified during a cancer screening with an actual radiologist, as opposed to receiving bad news from a bot.

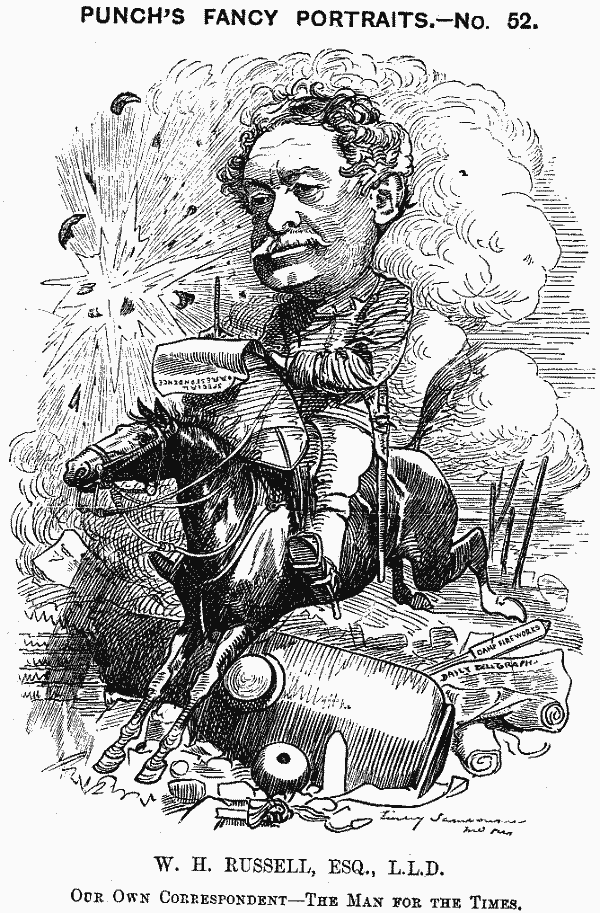

Another historical precedent for the power of the human touch: William Howard Russell.

“At the distance of 1,200 yards,” Russell wrote in a dispatch from the Crimean War in 1854, “the whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame through which hissed the deadly balls.”

At a time when the telegraph was starting to put a bloodless recitation of world events at nearly everyone’s fingertips, Russell made full use of the new technology by taking things far beyond rote summary. The Irish journalist put himself at the centre of vivid storytelling that connected with readers on an emotional level, and delved beneath official narratives. That hadn’t really been done before.

Not everyone currently working in a newsroom is a William Howard Russell. But cultivating a similar ability to use technology to elevate the human element in their stories might help more of them succeed, even as AI upends their industry.

When two AI-created albums mysteriously appeared online last year under UK folk singer Emily Portman’s name, her twin reviews were: “vacuous and pristine” and “drivel.” Most fans seemed to agree. Estimated royalties for the phony records amounted to less than $6 per track after several weeks.

If people want their music from AI in the future, they’ll make it known. In the meantime, there’s work available – the official tally of people employed as musicians in the European Union increased by nearly 30% between 2021 and 2023.

For a music industry long faced with declining physical album sales, enticing people to show up to see other human beings perform has become its dominant, recession-proof source of revenue. Not every band has navigated that transition smoothly.

Some went the way of the “sheik type.”

As many of his suave-but-silent contemporaries faded away, Ramon Novarro and other actors transitioned from one-dimensional caricatures to something more like real people up on the screen. Novarro’s later career had ups and downs, but it endured.

We all may not face imminent unemployment, but we are being confronted with uncomfortable questions about our ability to slot into a new world of work.

One question may be, are you a Ramon Navarro or a Rod La Rocque?

(If you’ve never heard of Rod La Rocque, there is a reason for that).

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Artificial Intelligence

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Jobs and the Future of WorkSee all

Zane Čulkstēna

February 16, 2026