How climate change is reshaping the global plastic pollution crisis

Climate change is actively reshaping how plastics behave in the environment. Image: Antoine Giret/Unsplash

- Climate change is actively reshaping how plastics behave in the environment, making them more mobile, persistent and harmful across ecosystems.

- Recent analysis examines the influence of climate-driven changes in temperature, weather events and Earth system processes on plastic pollution.

- Addressing these interconnected risks requires aligning plastic policy with climate action – not as parallel efforts, but as mutually reinforcing ones.

Plastic pollution is often framed as a waste management problem: too much plastic, used too briefly and discarded too carelessly. However, research shows that this framing misses a critical dimension: climate change is actively reshaping how plastics behave in the environment, making them more mobile, persistent and harmful across ecosystems.

Our recent synthesis of global evidence, published in Frontiers in Science, brings these two planet-wide crises together by examining the influence of climate-driven changes in temperature, weather events and Earth system processes on plastic pollution.

The result is a growing body of evidence indicating that plastic pollution is a dynamic, climate-sensitive stressor moving through land, water, air and ice.

Why climate and plastics are deeply connected global crises

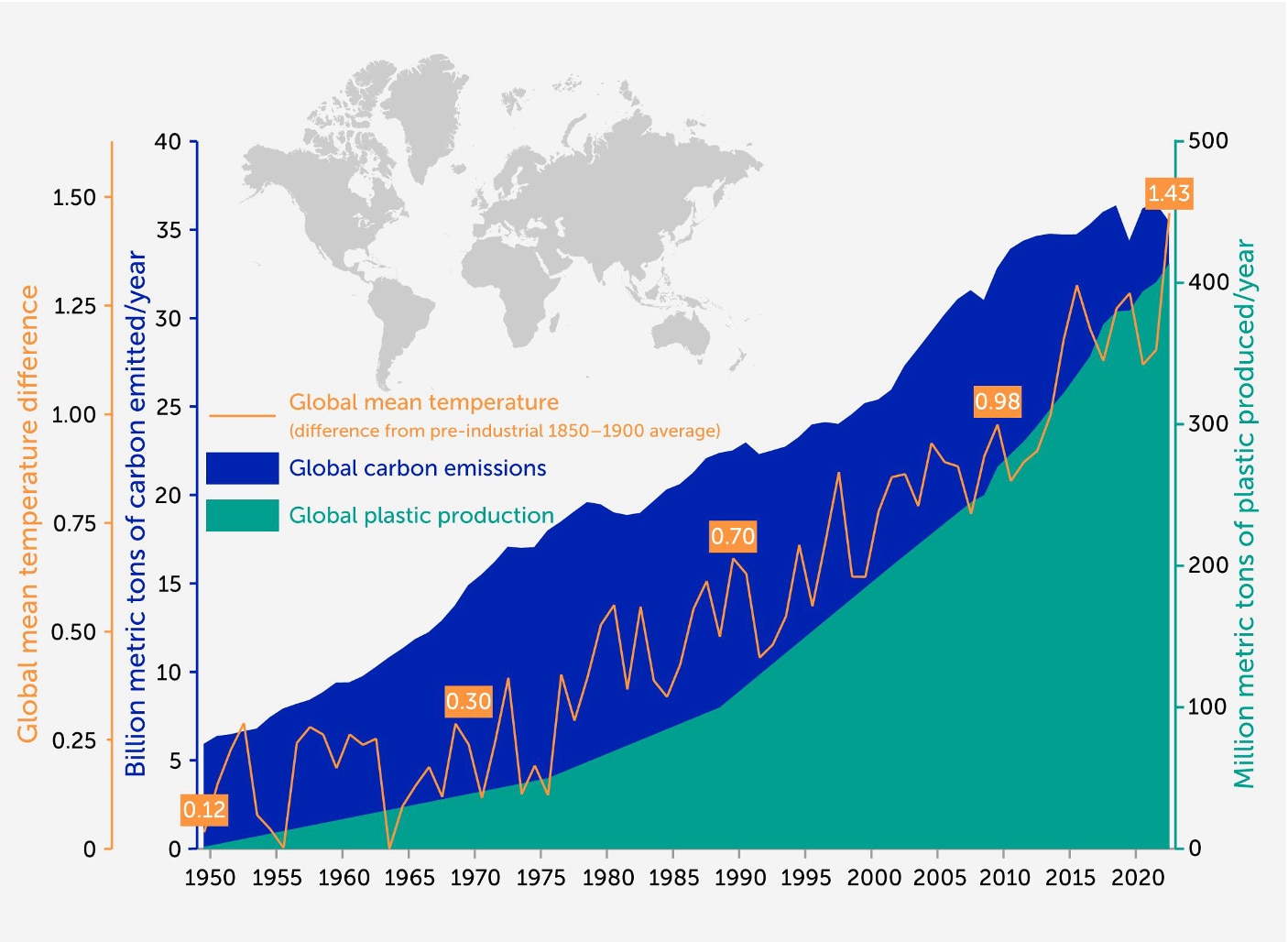

Plastic pollution and climate change share common roots in fossil fuel-based systems. Most plastics are produced from oil and gas, and greenhouse gases are emitted throughout their life cycle – from extraction and manufacturing to transport and disposal.

As global plastic production has increased dramatically since the mid-20th century, so too have the life cycle emissions of plastics.

The relationship also runs in the other direction – climate change is altering the environmental conditions that shape how plastics behave once they enter the environment. Warmer temperatures, stronger sunlight, shifting wind patterns and more frequent extreme events alter the rate at which plastics break down, disperse, and interact with living systems.

What emerges is a reinforcing feedback loop: plastics contribute to climate change, and climate change transforms plastics into more pervasive and harder-to-manage pollutants.

Climate change makes plastic a farther-reaching pollutant

Under warmer and more variable climatic conditions, plastics fragment more rapidly and travel more extensively through the environment. Heat, ultraviolet radiation and humidity speed up their chemical and physical breakdown into micro- and nanoplastics.

Floods, storms, wildfires and erosion from rising seas can remobilize plastic waste that was once relatively contained, transporting it from temporary sinks in landfills, riverbeds and soils into freshwater systems and coastal zones, as well as into the atmosphere, where wind patterns can transport plastic particles across continents.

A particularly striking example involves sea ice, long assumed to isolate plastic pollution. As ice forms, it traps and concentrates microplastics, temporarily removing them from surface waters. Warming-driven ice loss could reverse this process, releasing stored microplastics back into the ocean.

Climate change also affects how plastics interact chemically with their surroundings. Higher temperatures can increase the release of additives such as plasticizers and flame retardants, while plastics themselves can act as carriers for contaminants including metals and persistent organic chemicals. Warming conditions may enhance the transfer of these substances into food webs, compounding ecological and health risks.

From soils to seas: impacts across ecosystems

The combined pressures of climate change and plastic pollution are now being documented across a wide range of ecosystems.

On land, microplastics in agricultural soils have been shown to interact with heat stress and elevated carbon dioxide in ways that may reduce crop yields and disrupt soil microbial communities responsible for nutrient cycling. Sources include litter, wastewater, plastic mulch films and tyre abrasion.

In freshwater systems, zooplankton such as water fleas experience reduced survival or reproduction when exposed to both warmer water and microplastics. These organisms form the base of the food web, so any harm to them can ripple up to larger animals. For fish, elevated temperatures can increase plastic ingestion rates and intensify toxic effects.

Marine ecosystems reveal especially complex interactions. Filter-feeding organisms, such as mussels, which efficiently concentrate particles from water, can experience digestive and immune problems when exposed to microplastics in low-oxygen or acidic seawater. Even slight ocean warming can increase microplastic ingestion rates and increase their harmful effects on fish.

Evidence increasingly suggests that larger, longer-lived animals higher in the food web, such as orcas, may face disproportionate risks. These species accumulate plastics over time and are already vulnerable to multiple climate-related pressures. As a result, they may serve as early indicators of the combined impacts of climate change and plastic pollution on ecosystem stability.

Implications for global policy and coordinated action on climate and plastics

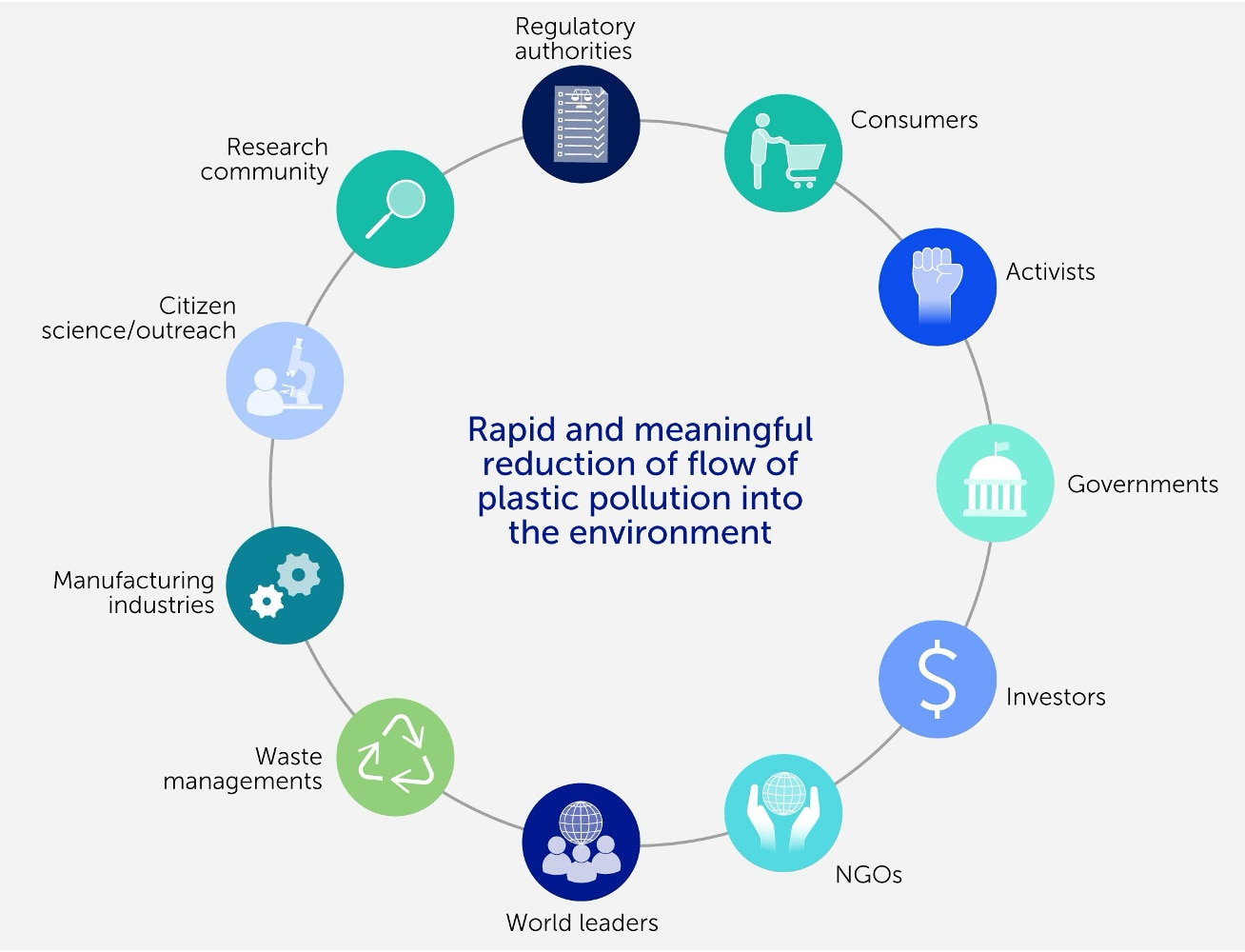

These findings challenge approaches that treat plastic pollution and climate change as separate policy domains. If climate conditions influence how plastics spread, persist and cause harm, then mitigation strategies focused solely on cleanup or end-of-life management are unlikely to keep pace as warming accelerates plastic breakdown, dispersal and toxicity.

For global initiatives concerned with planetary boundaries, biodiversity loss, food security and human health, this integrated perspective is increasingly relevant. It points to the need for shared metrics, harmonized monitoring and decision-making frameworks that reflect interactions across systems rather than isolated stressors.

The evidence also clarifies where action is likely to be most effective. Research into biological and technological cleanup approaches continues, but these methods are unlikely to substitute for prevention.

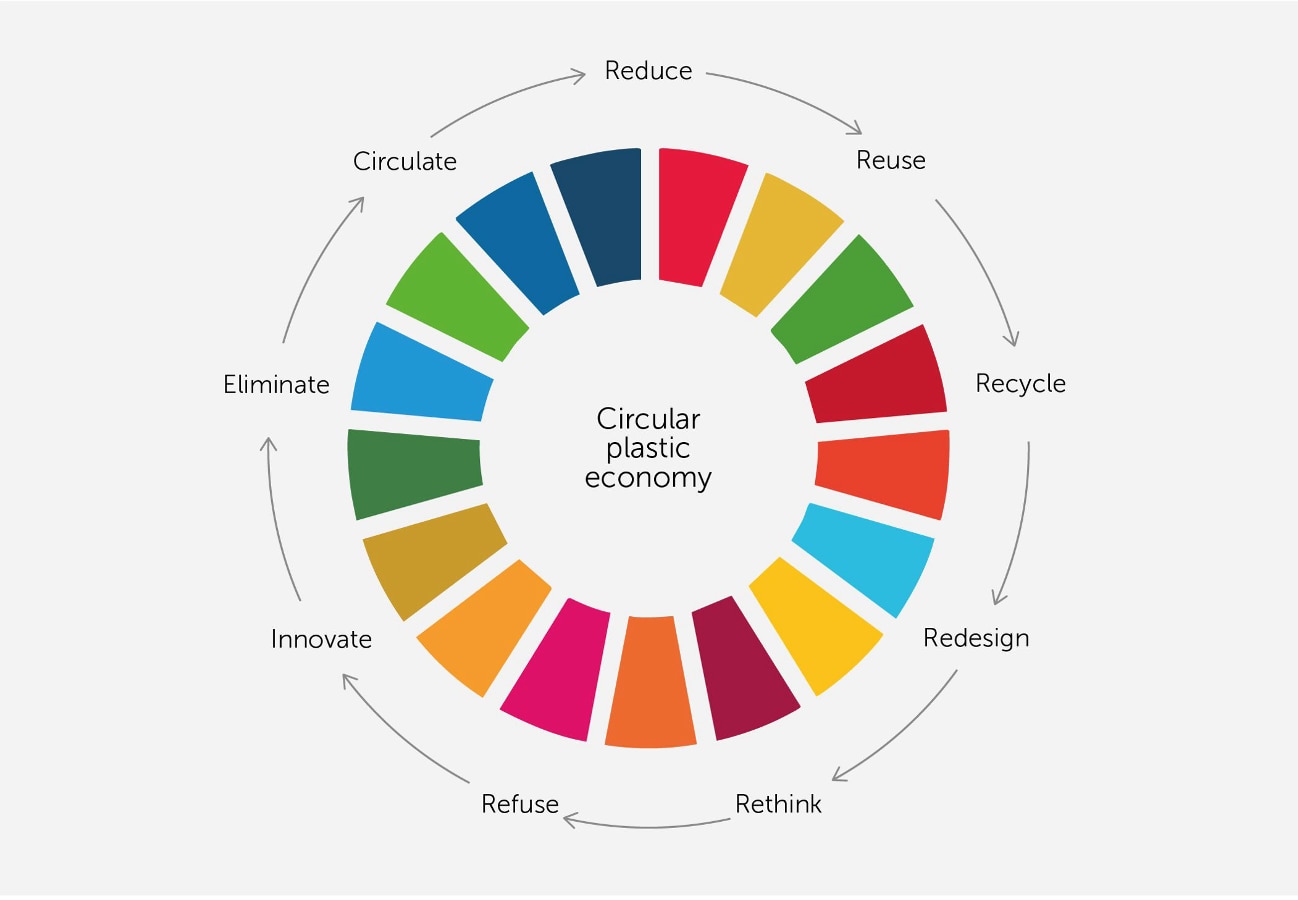

Reducing the amount of plastic entering the environment – by cutting unnecessary single-use plastics, redesigning products for reuse and improving recycling systems so they function at scale – remains the most reliable way to limit long-term harm.

At the same time, global standards for materials, additives and waste management would make plastic flows easier to track and compare, reducing data blind spots and limiting the unintentional “offshoring” of environmental impacts.

Taken together, these priorities align with broader efforts to move towards a circular plastics economy that minimizes waste, keeps materials in use longer and reduces emissions across the plastic life cycle.

Viewed through this lens, plastic pollution is not simply a waste problem, nor climate change a separate backdrop. We face a systems-level challenge that calls for coordinated approaches across climate action, materials design and environmental governance.

Addressing these interconnected risks requires aligning plastic policy with climate action – not as parallel efforts, but as mutually reinforcing ones.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Plastic Pollution

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

Tom Crowfoot

February 10, 2026