The Winter Olympics aren't immune to climate change. Here’s how the Games could change

Artificial snow has become a common feature at Winter Olympics - a solution to our warming climate that nevertheless comes with its own environmental challenges. Image: REUTERS/Yara Nardi

- The Winter Olympics are underway in northern Italy, but take place against a global backdrop of climate change and disruption to typical weather patterns.

- As mountain regions see reduced snowfall, a new World Economic Forum report finds fewer venues are likely to be able to host the Games.

- From artificial snow to schedule changes, here are some of the changes already taking place - and what’s being considered to support the future of the Winter Games.

The Winter Olympics are already well underway in Italy, the third time the country has hosted the Games.

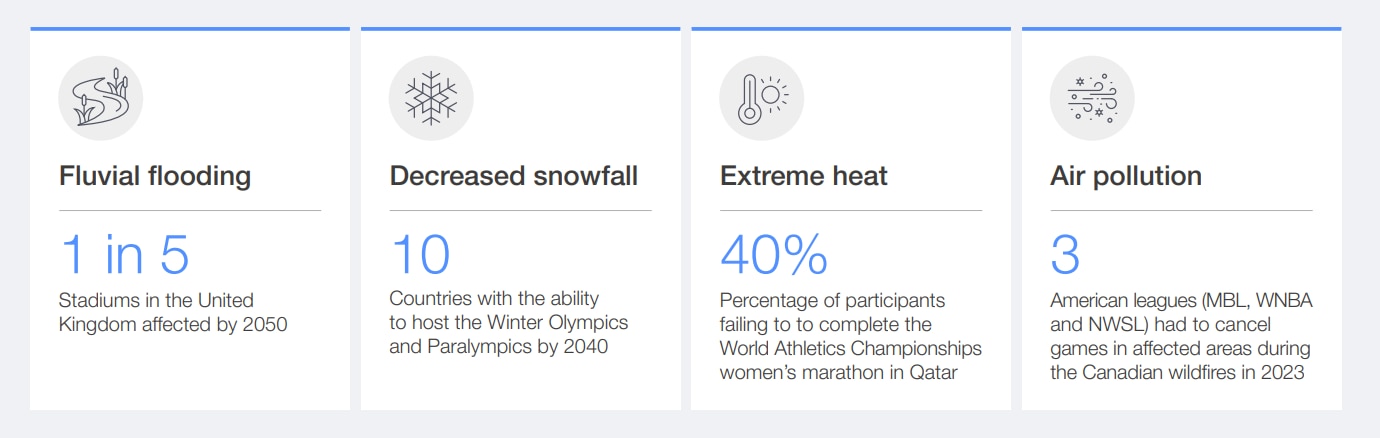

However, a January 2026 World Economic Forum report warns that a dwindling number of countries will be able to host the Games due to the climate crisis. Its analysis found that just 10 countries will have the ability to host the Winter Olympics and Paralympics come 2040, as a result of reduced snowfall.

The Sports for People and Planet report, published in collaboration with Oliver Wyman, cautions that “environmental risks ... dominate the global risk landscape for the coming decade, and represent an escalating operational and financial threat to the sports economy”.

A declining number of potential hosts?

The Forum report echoes warnings from a 2024 study, published in Current Issues in Tourism, that found a declining number of viable host locations.

And, while the number of host venues remains geographically dispersed, this decline is already underway. The report highlights the need to "consider climate change in future host selection processes", with safety and fairness a key consideration. Additionally, it found the risks to the Paralympic Winter Games to be even higher, as historically these have been held after the Olympics, and so later in the winter season.

In 2023, Olympics organizers delayed a decision on the 2030 hosts to give themselves more time to explore the climate implications on host venues. The next two Winter Olympics will be held in the French Alps and Salt Lake City in the US, respectively.

So what are the organizers of the Winter Olympics and Paralympics already doing - and what might they need to do in the future?

Artificial snow

This is nothing new. It was first used at Lake Placid in 1980. But, come the last Winter Olympics in Beijing in 2022, its use had expanded, with the percentage of artificial snow used in Yanqing at least 90%, according to the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

And while it was produced using renewable energy, the use of artificial snow has environmental considerations of its own, from water use to energy consumption. The BBC reports that some 222 million litres of water was used to make artificial snow during the Beijing Games.

Artificial snow is in use again at Milano-Cortina 2026, in part due to its ability to offer consistent quality throughout an extended period of competition.

And with the Forum report warning of the impact of declining snowfall, it’s likely artificial snow will remain a part of future Games.

Changing the schedule

The authors of the 2024 study suggest that moving the Games to earlier in the year could significantly increase the number of potential hosts, and in particular reduce the risks to the Paralympics.

They wrote in The Conversation in February 2026, ahead of this year’s Games, that “holding the Winter Olympics and Paralympics three weeks earlier in the year has tremendous potential to increase the number of climate-reliable hosts.”

Overlapping the two events or splitting them across different cities or years to mitigate the risks is another suggestion. However, the IOC’s agreement of ‘one bid, one city’, which states that “the IOC will continue to make it obligatory for any host of the Olympic Games also to organize the Paralympic Games” would need reconsideration.

Other suggestions include lengthening the Games to take place over closer to 20 days, compared to the current 16. This would allow for flexibility if weather conditions caused delays to some events.

Host the Games over a wider area

There could also be benefits to expanding the area over which events are held, in order to take advantage of more climate-resilient areas.

An article in Yale Climate Connections suggests wider regions that might need to be considered, including the Rocky Mountains across the United States and Canada or the entire Tyrol Region of the Alps.

This year’s Games are spread over a much wider area, compared to some previous editions, with 2026 the first Winter Games to have opening ceremonies in two locations. The IOC says these will be the "most widespread games in Olympic history", spanning some 22,000 square kilometres.

Of course, there’s a challenge in hosting events over a wider geographical area, with potential increased emissions as a result of travel between sites. However, it’s been suggested there could be some mitigation of this - and improved sustainability - as a result of making better use of existing venues, rather than building new ones.

A symbol of something bigger

Whether it's the triumph over adversity, the unifying power of sport, or the enduring appeal of the underdog, the Olympic Games have long symbolized something greater than competition alone. In this snapshot of how societies are adapting to climate change, that sense of deeper meaning remains.

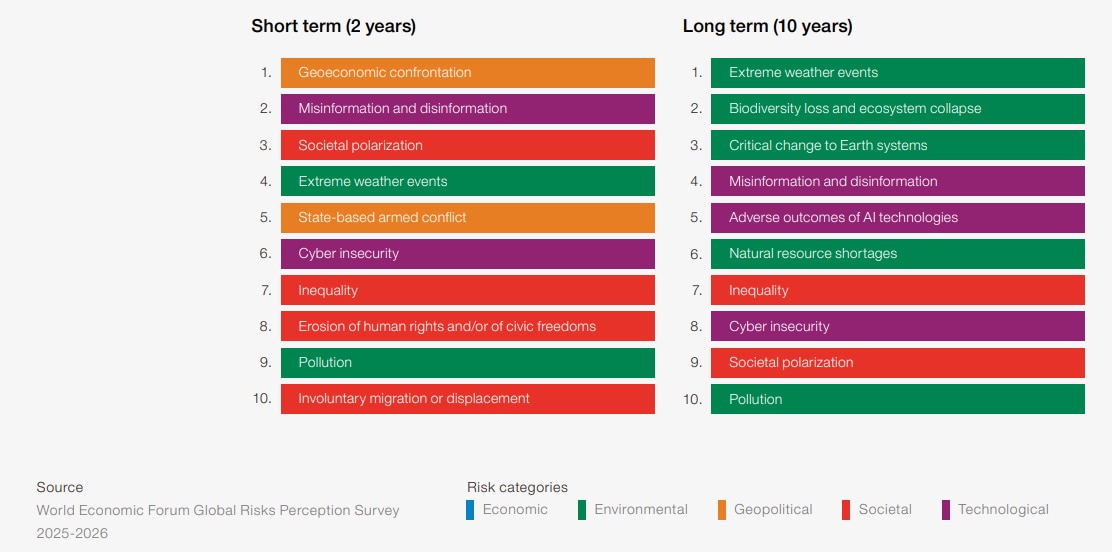

While the Forum’s latest Global Risks Report sees fewer environmental concerns over the short term (see table below), they continue to dominate the long-term risks outlook.

At the Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos this year, a session on glaciers explored both the threats and the innovations emerging in mountain regions as ice retreats. ‘The Snow Factor’ highlighted how scientists, policymakers and local communities are working together to safeguard glaciers, water resources and the billions who depend on them - often through the use of new technologies.

So while debates over artificial snow or ski jump schedules might seem minor, they point to a far larger question: how climate change is reshaping the world’s mountain ecosystems, and the people and institutions striving to protect them.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

Sadaf Hosseini

February 12, 2026