Our food system is bust. This innovative three-step plan could fix it

Image: REUTERS/Mike Blake

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Agenda in Focus: Social Entrepreneurs

How on earth did food get so complicated? After all, on the face of it, it’s really quite simple: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly Plants,” explains food activist Michael Pollan.

But somewhere along the way, it all went horribly wrong.

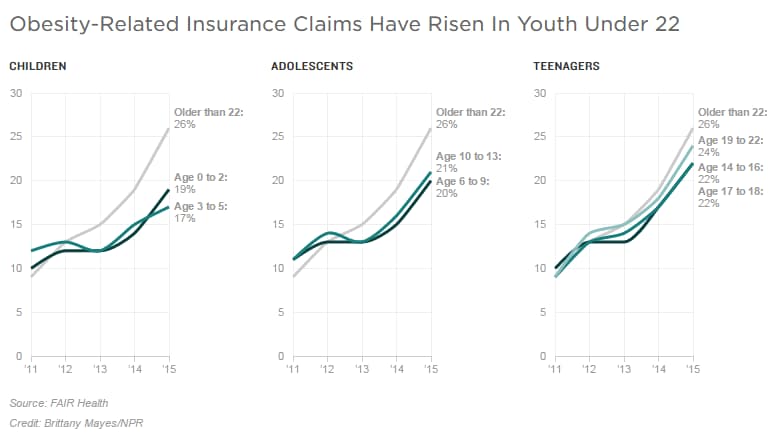

Take the US, the land of big gulps, super-sized meals and fast food restaurants. Since the 1970s, childhood obesity rates have tripled. Obesity-linked conditions – high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea – are also on the rise among young Americans.

The only way out of this crisis is to have a “real food” revolution, and Kimbal Musk – a Schwab Foundation social entrepreneur of the year 2017 – is one of a new generation of activists leading the way.

Once a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and serial investor, today he’s working to transform the way we produce and consume food. We spoke with him to find out more about his revolutionary plans.

Food has always been your passion, but until recently you were better known for your work in the world of tech. What changed?

I’d always been fascinated by food and nutrition – I trained at the International Culinary Center, and I’ve had a restaurant since 2004 – but my day job was working in technology. Food was more of a side project.

Then, in 2010, I was on a skiing trip when I flipped off a tube and landed in the snow. I broke my neck and was paralyzed. I remember being wheeled into surgery and thinking, “If I recover from this, I will give myself permission to do what I love. I won’t care about the money, I will focus entirely on the things I believe in and the things the world needs.” When I woke up, I could walk, and I’ve never looked back since.

Breaking my neck was the worst thing that ever happened to me, but it was also the best: it gave me a reason to restart my life in a direction that mattered.

You’ve called for a “real food” revolution. What is that and why do we need one?

The industrial food system is designed to give us highly calorie, low-nutrition food. This food leaves us malnourished and obese – we are literally fat and starving at the same time.

These eating habits are already starting to take their toll on our health. In California, for example, 55% of people are diabetic or pre-diabetic. Now that’s known as one of the healthiest US states, so you can only imagine what it is like in other parts of the country.

But it’s not just consumers who are paying the price: farmers are, too. Working in the industrial food system is a total misery for most farmers. They are barely making ends meet, even though they own huge swathes of land – which, when they die, will be sold for vast sums of money. “Live poor, die rich” is something we often hear farmers say.

So we need a “real food” revolution to get us back on track, to take us back to basics.

How did we reach this point?

We were spun a lie: we were told that a sign of progress was not having to cook for ourselves. Instead, we could eat out at fast-food restaurants or buy highly processed TV dinners.

The internet age is helping dispel that myth. Before the internet came along, we didn’t have access to all this information. Food companies could just do what they wanted, and we had to trust them. But now, with the digital revolution and the information this has put at our disposal, we’re starting to realize this trust was misplaced.

Another lie we still hear is that “healthy eating” is hard or expensive. The idea that people can’t afford real food is just not true – you can roast a chicken and vegetables to feed a family of four for $10. You’d struggle to feed as many people at a McDonald’s for the same price.

And if you’re cooking for yourself at home, you don’t need to be making vegan milkshakes or haute cuisine. Just knowing what is going into your meals – and therefore your body – is a start.

It seems like such a simple challenge, but many people have tried to tackle it and failed. What are you doing differently?

Rather than spreading ourselves very thinly, we try and go deep into a community and bring about change through three different but complementary approaches.

The first is making farm-to-table dining more accessible and affordable.

Back in 2004 I opened a restaurant, The Kitchen. We source all our produce from local farmers, and we only serve fresh, seasonal food. But one complaint we heard again and again was the cost: many people simply couldn’t afford to eat there. It’s not just affluent urbanites who want healthy, local food, so we worked with our farmers to offer something at a lower price point. That’s where the idea for the Next Door restaurants came from. Prices there are around one-third cheaper than you would see at your average farm-to-table restaurant. There are currently three, but our plan is to have 50 across the US heartland – from Denver to Pittsburgh – by 2020.

The second focuses on education. As I said, we’ve been misled by the industrial food industry for some time now. If we want to bring about change, we need to teach our children what “real food” means.

To do so, we’ve built Learning Gardens in schools across the country. They’re different to your old-fashioned school gardens in two ways: they’re permanent structures that are built to last, and they’re on a much bigger scale. That means we’re able to reach 150,000 children every day. Almost all (98%) of teachers involved in the project say these gardens have helped increase their students’ knowledge of healthy foods.

The third one – Square Roots – is about creating the next generation of real food entrepreneurs.

In Iowa, 60% of farmland is owned by people over 75. Who will be tomorrow’s producers once these people are gone? For many millennials, farming just isn’t a career path they’ve ever considered. But there are enormous opportunities out there for those innovative enough to rethink traditional farming.

The Square Roots campuses – urban farms inside shipping containers – provide the space for this next generation of farmers to grow produce (the equivalent of two acres of outdoor farmland in just one, 320 square foot module).

More importantly, though, they teach these young people the entrepreneurial skills they’ll need to go away and continue the real food revolution.

Interview by Stéphanie Thomson

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Industries in DepthSee all

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 5, 2024

Douglas Broom

April 3, 2024

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

March 28, 2024