Why we urgently need a Digital Geneva Convention

Image: REUTERS/Jim Urquhart

This article is part of the World Economic Forum's Geostrategy platform

More than 30 governments have acknowledged that they have offensive cyber capabilities. However, unlike with conventional weapons, cyber arsenals are clandestine and intangible. Their source is difficult to track and identify. It is therefore likely that the real number is not only much higher, but will grow in the coming months and years.

Moreover, because of this ambiguity, governments are more willing to deploy these weapons – testing capabilities with strikes, while tuning their strategies behind closed doors, writes Kaja Ciglic, Director, Government Cybersecurity Policy and Strategy, Microsoft, in her contribution to the Observer Research Foundation’s collection of essays, Our Common Digital Future.

The cyber arms race is clearly under way. However, the risk and dangers of cyber weapons are not well understood. These two issues together – the clandestine nature and the unpredictability of offensive online activity are creating vulnerabilities at a scale and speed that we haven’t seen before. How can we manage the resulting risk, risk that can manifest itself both online and offline?

International law applies to cyberspace

Microsoft believes that existing international law applies to cyberspace. This should hardly be a surprise. Online activities involve real people using tangible objects that have long been subject to various legal frameworks. However, it took governments a little longer to come to this conclusion.

The United Nations almost two decades ago set up a working body to ensure agreement is reached on how to handle the then relatively new field of information technology (IT), and in particular the increasingly difficult question of cybersecurity. It took a while, but in 2015, the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (UN GGE) confirmed that international law applies to cyberspace.

The consensus report was unanimously adopted by the 20 countries that participated in the process, including the USA, China, Russia, France, and the United Kingdom. This position has been subsequently reaffirmed in several statements by individual governments, and indeed by the Group of 7 (G7) in early April of this year.

Significantly, this stance is echoed in bilateral cybersecurity deals between what I call “cyber super- powers”.

Today, therefore, the only way to ensure that the behaviour of states in cyberspace is subject to certain rules and norms is through the recognition of international law

”From the Sino-Russian, US-China, US-India, and Sino-Anglo cybersecurity agreements to this year’s China-Australia cybersecurity cooperation agreement, there are many and varied references to the UN GGE and expressions of support for cybersecurity norms. Regional groups have similarly acknowledged the applicability of international law to cyberspace, including the ASEAN Regional Forum and the Organization of American States. Bilateral and regional agreements are important steps, but they do not address the need for a strategic international cybersecurity framework.

Today, therefore, the only way to ensure that the behaviour of states in cyberspace is subject to certain rules and norms is through the recognition of international law. The challenge, from our perspective, is not about the applicability of international law but its sufficiency and implementation during times of peace.

Commitment to international law is not sufficient

Despite what appears to be almost unanimous agreement, it is proving difficult to travel from broad positions of support to concrete commitments. The UN GGE has been a key and constant part of this journey, the main highway, where other fora represented minor motorways. Now, we seem to have however hit a dead end.

So where do we go from here?

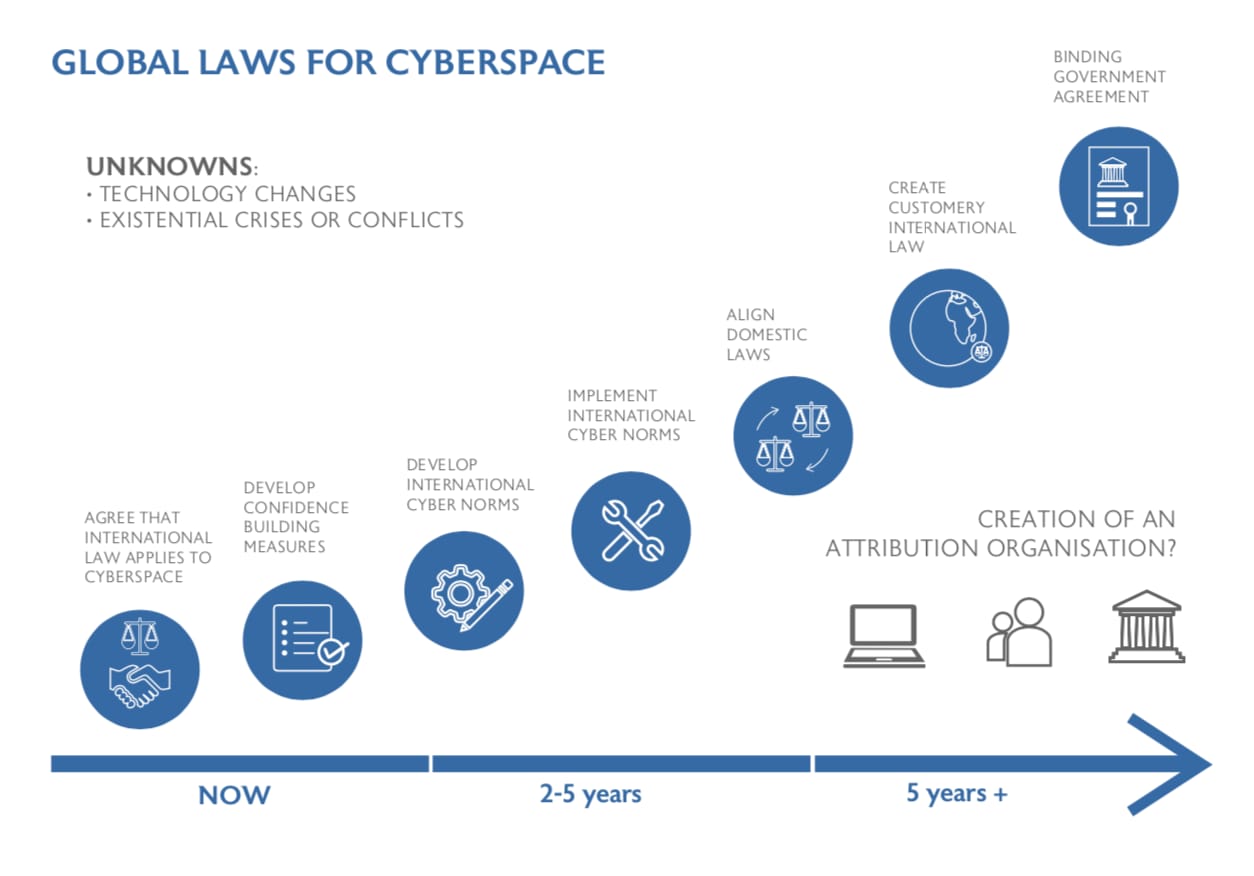

We do have the advantage of starting this complicated journey with an agreement on 11 cybersecurity norms from the 2015 UNGGE. We also have several proposals, including those put forward by Microsoft as part of the Digital Geneva Convention, and even partial agreements within narrower groups, such as the G7. But these are barely the first couple of steps on a long road.

To make significant progress, we have to unmask the fact that unfortunately there is little specificity in the agreements reached so far. This situation allows states to continue to act in violation of established norms, without the international community having any recourse to respond. For example, international law prohibits the use of force by states except in self-defence in response to an armed attack, and the UNGGE norms call for states to refrain from international malicious activity.

The questions are how these statements should apply to cyberspace, how concepts such as malicious activity are defined. This is where the work so far falls short. To move forward, these gaps will need to be identified and addressed. The work of the Global Commission on Stability of Cyberspace around what constitutes core internet infrastructure could yield important results in this regard.

Moreover, the current list of norms does not fully address the core drivers of instability in cyberspace. A limited set of additional cybersecurity norms in areas where existing rules are either unclear or may fall short in protecting civilians in cyberspace need to be developed.

This could include norms which explicitly articulate protections for civilians, even if they are implicitly contained elsewhere in international law. The development of these norms should be informed not just by governments, but also by civil society and the private sector.

Third in this process is the actual implementation of established norms, which – underpinned by the legal opinions of experts in this topic – would lead to the development of customary international law.

In this process, governments need not only adhere to the norms themselves, but hold other nation states accountable – whether through punitive actions, such as economic sanctions or words of condemnation. Even where there seems sufficient evidence, states often choose not to act, in an effort to not rock other relations. But that is seen by other governments as an example that such behaviour is permissible.

Only then we reach the final step in this process – the development of a binding international agreement akin to a new or “Digital” Geneva Convention. Most experts agree that this final step is likely to take decades, something we have been very clear about when we launched our idea earlier this year.

Core principles to guide progress towards a Digital Geneva convention

So, what did we introduce back in February? We called on the world to acknowledge that we live in a world that is growing more insecure every day. We suddenly find ourselves living in a world where nothing seems off limits to nation-state attacks, online. There are increasing risks of governments attempting to exploit or even weaponise software to achieve national security objectives, and governmental investments in cyber offence are continuing to grow.

Our proposed response was a Digital Geneva Convention, that would commit governments to adopt and implement norms that have been developed to protect civilians on the internet, without introducing restrictions on online content. Just as the world’s governments came together in 1949 to adopt the Fourth Geneva Convention to protect civilians in times of war, a Digital Geneva Convention would protect citizens online in times of peace.

Moreover, we acknowledged that no single step by itself will be sufficient to address this problem. We encouraged the tech sector to step together to do more, given its unique role as the internet’s first responders and commit ourselves to collective action that will make the internet a safer place, affirming a role as a neutral Digital Switzerland that assists customers everywhere and retains the world’s trust. We also called for greater action in improving the current attribution efforts – a critical challenge in the online space.

However, as mentioned above, while the direction of travel might be clear, we still need to map out the route to get there because, as highlighted before, the main highway has been washed away. I believe that if we regroup as a wider community of politicians, diplomats, technologists and citizens we can find our way to the next step. Not only are there numerous existing fora and groups that could be leveraged for this purpose, there is increasing recognition that something needs to be done, and that it needs to be done before a cyberattack escalates beyond control. In other words, something needs to be done now.

However, we also need to be clear about how we are to make this journey. There are three main principles that must be recognized and adhered to for any effort to be successful:

- We must have an open, multi-stakeholder process that represents governments, the tech sector, civil society groups and academia;

- All parts of the world need to be represented and actively involved, from north and south, east and west and not just the “usual suspects”;

- The process cannot be locked away in committees that hide behind technical language, it must be open and transparent, so that everyone depending on cyberspace can see what is happening and can hold their governments, the tech sector and others to account.

If we ignore these basic principles and allow the process to fall back to closed, narrow groups then the world will stay where it currently is. We may make incremental, patchwork progress but it will be far slower and more limited than the rapid evolution of cyberspace and the attacks that take place within it.

Microsoft has made the case for a new commitment to the role of international law in cyberspace by calling for a Digital Geneva Convention. Our proposal represents the end of the journey I described here. The real question in our minds is therefore not how fast we can get to a new Convention, but how quickly we can make meaningful progress on the path outlined above. Waiting emboldens the status quo, which means more attacks on civilians in cyberspace – with ever-increasing consequences, effectively making cyberspace a lawless territory. We won’t get there tomorrow. While this will be a journey through many iterations and staging posts, the destination of a stable and secure cyberspace will surely be worth the effort.

The Evolution of International Collaboration and Law Related to Cyberspace and Security, Kaja Ciglic, a contribution to Our Common Digital Future, published by the Observer Research Foundation.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Drivers of War

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Resilience, Peace and SecuritySee all

Shoko Noda and Kamal Kishore

October 9, 2025