The Arctic recently sent us a powerful message about climate change

The Beast brought cold air from Siberia to cities unfamiliar with such harsh winter conditions, such as Rome.

Image: REUTERS/Hannibal Hanschke

Gail Whiteman

Hoffmann Impact Professor for Accelerating Action on Nature and Climate, University of Exeter Business School, University of ExeterStay up to date:

Climate Crisis

Arctic scientists aren’t usually afraid of a little cold. Windy conditions don’t usually get us howling. The beasts we pay attention to are usually polar bears. But last week’s “Beast from the East” triggered a few anxious conversations.

Social media memes aside, our problem isn’t this one extreme weather event per se. Our key fear is that the Beast isn’t really from the East – its birthplace was farther north.

Compelling scientific evidence suggests that the Beast actually comes from the high Arctic, and it’s not the only weather monster to emerge from that region.

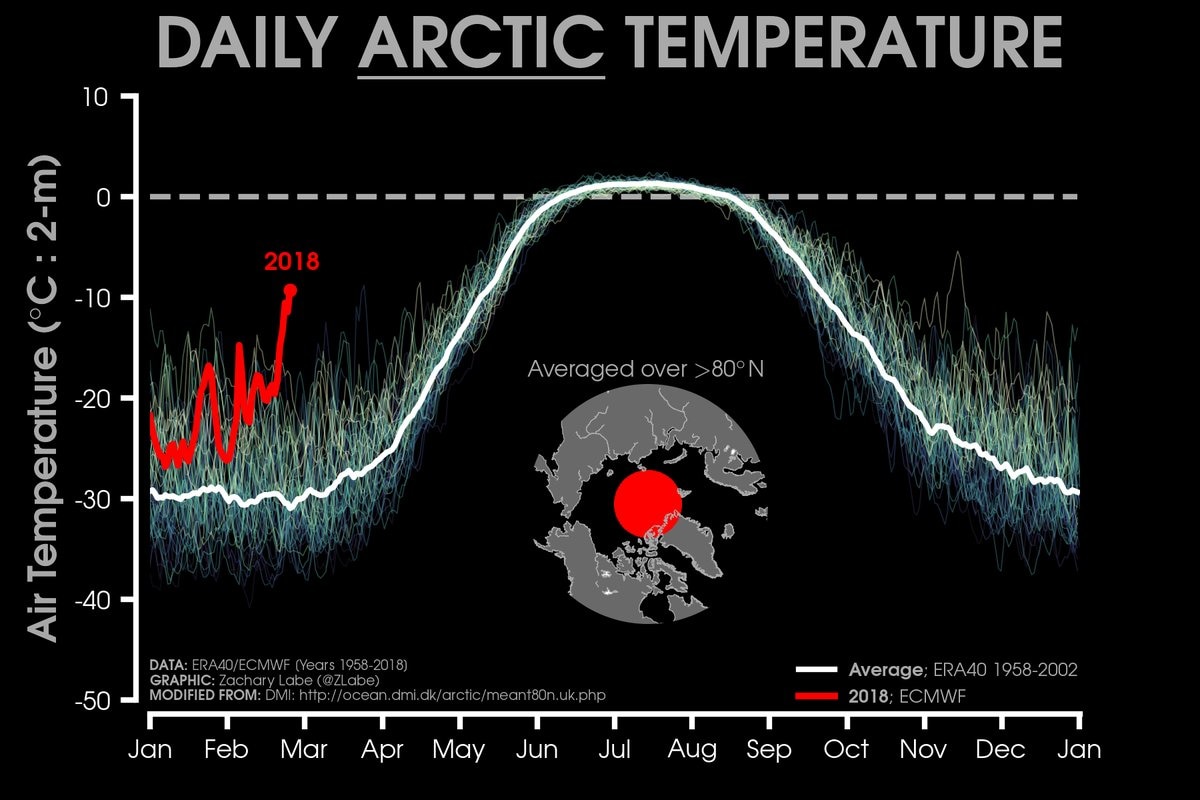

As some media reports have identified, alongside the freezing conditions in Europe, we’re simultaneously seeing exceptional warming happening over the Arctic. While the Beast screams and howls outside our windows in Europe, the Arctic is 20 degrees Celsius (36 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than it should be right now north of 80 degrees North.

The Arctic has had warm spells before. So what’s the big deal? The big deal is that scientists have been monitoring the Arctic for decades and have conclusively shown a long-term, significant warming trend. In fact, it’s warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the globe. This warming is accompanied by other major Arctic-wide changes in the ocean, atmosphere and land.

The most dramatic changes, though, are with Arctic sea ice – the ice that floats on top of the Arctic Ocean. The summer sea ice extent, for instance, is well-known to be in rapid decline: the 11 lowest extents have all occurred in the past 11 years. Winter sea ice, too, is now following the same track, with this year’s winter ice extent at its lowest value ever, beating the previous record that happened only last winter.

In 2017, the Arctic winter ice set the lowest level on record, but we’ve broken that record again. This is not the gold medal we want to win.

This is all bad news for the Arctic ecosystem and the people that live there. But the really bad news is that scientists have recently linked rapid Arctic warming to extreme weather farther south. Be it frigid cold spells, prolonged floods, persistent warmth, or long dry spells, it’s the persistence of weather patterns that is the connection, according to research. When weather conditions stick around a long time, extreme events can happen, hammering away at the world as we know it. That cold Beast from the East may be lurking for longer because the Arctic is so darn warm.

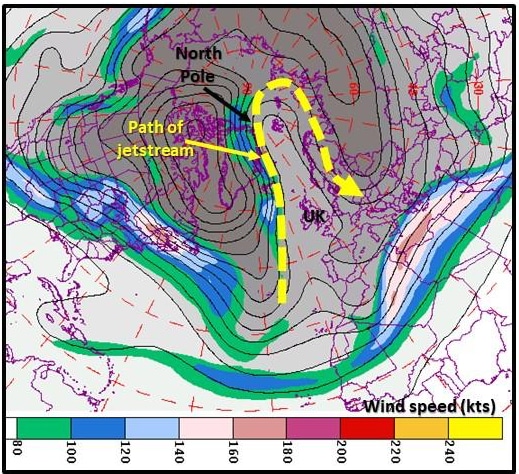

Right now there’s a so-called 'blocking high' parked over Greenland that’s causing the jet stream to shoot northward towards the North Pole east of Greenland, with a hair-pin southward turn over Europe. It’s bringing the heat into the Arctic and the cold into Europe. Scientists know this because we measure it in detail every few hours. See for yourself!

To understand the real impact of the Beast (and its future brethren), we need to understand the bigger picture: the influences of the Arctic on our weather and its impacts on societies everywhere. The Beast started out as too much warmth in the Arctic, which displaced the cold air into Siberia, which then oozed eastward into cities unfamiliar with such harsh winter conditions: Rome, London, Zagreb.

It’s critical that world leaders understand this global process that starts with excessive greenhouse gases and causes Arctic sea ice to melt. Diminished summer sea ice is connected to winter weather through complex processes that create “memory” in the system. And we’re seeing an expression of that connection now. Scientists expect further Arctic warming will make all sorts of weather conditions in many geographic locations stick around longer – be it hot, cold, wet or dry – any of which can become extreme. We are concerned that things are only going to get worse because we are still dumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

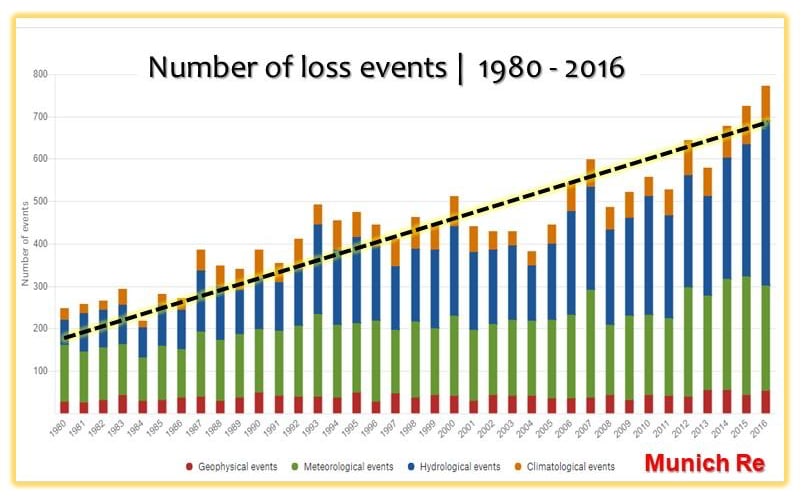

The real nightmare begins if those quirks, or anomalies, in the Arctic are happening more often, and it looks like they are. Persistent cold spells, particularly in central and eastern Asia, have become more frequent. From mid December 2017 through to mid January 2018, western North America experienced record-breaking high temperatures, drought, and low snow-pack, while the east was cold and snowy. A similar pattern prevailed in Eurasia.

Global risk experts agree. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report, extreme weather is the number one risk in terms of likelihood, and the number two in terms of impact. The Beast is to be expected, and we have reason to fear.

Is it fair to say that the Arctic is a barometer of global risk? We think so because it all comes down to physics – a warmer Arctic means thinner sea ice, an earlier melt, a later freeze-up, and a greater likelihood of extreme weather events throughout the Northern hemisphere. And that brings more trouble down the road.

We’ve set up the Arctic Basecamp at Davos for two years running, to raise awareness of the drastic change underway in the Arctic and the risks that it poses to all of us. The basecamp is a creative and immersive environment that gives attendees the opportunity to learn about both the damage being done to the polar regions, and the technology solutions that are reducing carbon emissions.

As scientists, we need to bring the facts, the hardcore evidence, into discussions of global risks. And then global climate leaders like Christiana Figueres (former executive secretary of the the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) and leaders from business, politics and civil society can bring the solutions. The Arctic Basecamp draws on research from Mission2020, a global campaign to accelerate action on climate change, enabling the world to reach a turning point on greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, and creating the conditions in which all of the sustainable development goals can be achieved.

If we were on the main stage this week, we would say very simply: urgency, urgency, urgency. The Beast reminds us that extreme weather brings unpredictability and risks.

We’re only three months into 2018. Yet we’ve already seen a parched California, a frigid eastern US, two “storms of the century” in New England, and a record-breaking heatwave in Florida. On the other side of the world, ski races at the Olympics had to be postponed because it was so cold and windy. Then comes the Beast from the East. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events is entirely consistent with scientific expectations. And this is costing us all a lot of money, and more importantly, lives.

In the US, 2017 was the most expensive year ever for extreme weather events, racking up costs of over $300 billion in destruction and disruption. Not all of it can be tied to the Arctic, of course, but increasingly extreme weather in the northern hemisphere is.

How bad could it get? We don’t really know. We see these kinds of bizarre conditions happening more often. But predictability of when and where they will happen is still not very good. It’s one thing knowing there will be greater frequency of extreme weather, it’s another to predict the when, where, and how bad.

What’s our message to world leaders? The disease that’s causing all these symptoms is our addiction to fossil fuels. And to slow down the disease’s progression, there’s really only one treatment: to cut our carbon emissions any way we can do it. We need to bend the emissions curve by 2020, or we may face a bigger Beast.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Anurit Kanti

July 15, 2025

Sebastian Buckup and Beth Bovis

July 10, 2025

Majlinda Bregu

July 9, 2025

Tom Crowfoot

July 8, 2025