To feed 10 billion people, we must preserve biodiversity. Here's how

The threats to bees and birds are directly related to our ability to feed the world - which is why we must act now Image: REUTERS/Suhaib Salem

Maria Helena Semedo

Deputy Director-General for Climate and Natural Resources , United Nations Food and Agriculture OrganizationThe threats to bee colonies around the world have been well publicized. Less well-known is that with many fruit and vegetables still reliant on pollination, what happens to bees, bats or birds has a direct effect on our shopping baskets.

Without biodiversity, humanity cannot maintain the essential ecosystem services that enable food production. The damage cuts deep – and presages even worse. For some species, extinction rates are now 1,000 times their historic levels. At the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), we estimate that a quarter of livestock breeds may not be with us much longer. One-third of the world’s land is degraded by erosion, compaction, salinization or chemical pollution. Millions of hectares are lost annually to drought and desertification.

Global thinking about agriculture has only recently outgrown the orthodoxy of the Green Revolution: produce more to feed the greatest number. How we produced, and at what cost, did not much matter. The urgency of securing humanity’s right to food trumped the necessity to preserve our planet.

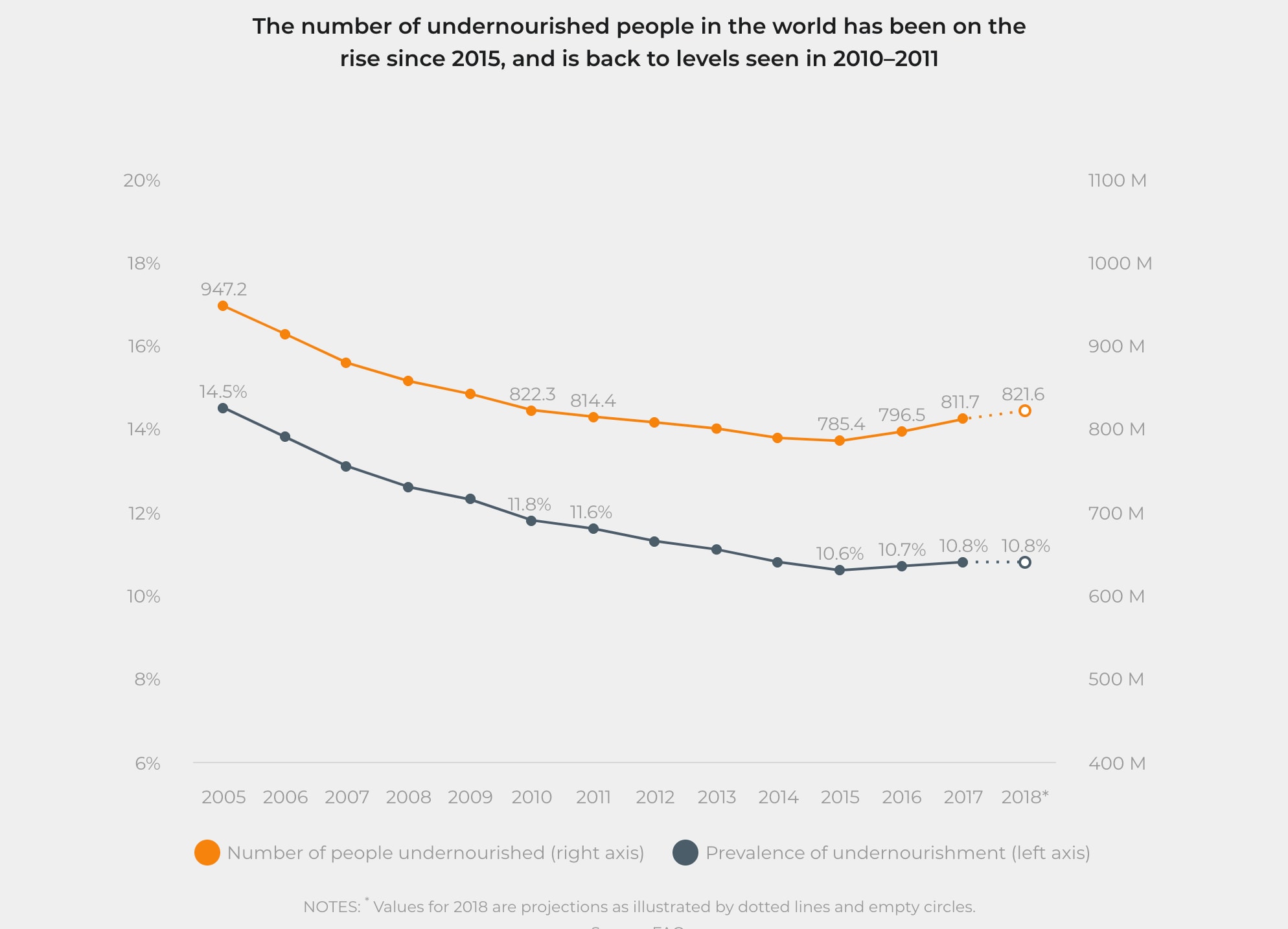

The result? We now produce more than enough to feed all of humankind, yet over 820 million still go hungry. Almost 830 million are obese. Meanwhile, species and genetic resources are falling prey to population growth, rampant urbanization, unsustainable consumption patterns, deforestation and climate change.

Belatedly, we are beginning to understand that far from opposing principles, ending hunger and safeguarding biodiversity are two facets of a single moral and policy imperative; that feeding people to the detriment of the environment is neither feasible nor desirable.

Awareness must now be followed by action. Having committed to achieving the Goal of Zero Hunger by 2030, we need to crack the science-policy interface that will unlock dramatic outcomes – and fast.

How? Here are some suggestions.

The relentless march of mono-cultures – sugar cane, maize, soybeans or rice – is colonizing the global food supply, robbing our palates of gustatory variety and our bodies of essential nutrients. Around the world, persistent hunger is accompanied by an oversupply of empty calories and the spread of nutrient-poor diets. These are creating an obesity crisis with severe public health consequences – as well as leaving fewer fallback options should one crop succumb to disease. To a large extent, biodiversity loss is a byproduct of our willingness to allocate ever more land to grow too much of too few things. Entire food cultures are being lost.

At FAO, one way we encourage more varied approaches to agriculture is through an initiative called the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). The name may not trip off the tongue, but the concept is simple: it broadens the traditional notion of a protected area to include a human community’s time-honed relationship with it. Every such biosocial landscape has its distinct agricultural profile – whether the ancient olive trees of Territorio Sénia in Spain or the underground irrigation systems of Qanat in Iran. To preserve and nurture it is to save an ecosystem, a capsule of nutritional wisdom, a resilience safety valve.

Biodiversity loss should be tackled holistically, as part of overarching policy packages that combine incentives for sustainable agriculture, the fight against rural poverty, measures to advance food security, and climate change adaptation and mitigation. Agro-ecology and agro-forestry, as well as biodiversity-friendly practices in fisheries and aquaculture, must become the norm. By the same token, conservation schemes should, wherever possible, include provisions for sustainable use of resources.

From a governance perspective, this also means that agriculture and environment ministries (and the bureaucracies and interests lined up behind them) must shed their culture of mutual adversity and learn to deliver as one. Conversely, communities – often indigenous – with demonstrably sustainable approaches to agriculture should be encouraged to maintain them; they must be empowered to design local micro-policies that promote both ecosystems and diverse diets.

We should recognize that food security is not just about food crops – in other words, not just about farming and cultivation. Sustaining and aiding our universe of fields and orchards, of pastures and ponds, is a wealth of ‘associated’ biodiversity. Myriad fungi, protozoa, acari, earthworms and assorted bugs interact with each other, and with plants and animals, in ways that we have yet to fully comprehend. We barely know what happens beneath our feet: the vast, teeming life hidden in soils – with its role in nutrient cycling, in regulating the dynamics of organic matter, or in carbon sequestration – is in effect terra incognita; as many as 99% of bacteria present in the natural world are still waiting to be studied. Uncovering the secrets of associated biodiversity should be a scientific quest for our era, properly funded and politically supported.

Would doing all the above suffice to achieve food security within a generation? Unlikely. But let me turn the question on its head: do we stand a chance of achieving food security unless we put biodiversity at the heart of our mission? Not remotely.

What is now needed is a quick, decisive change of direction. Anything less, and feeding the planet’s projected 10 billion people will be a wild dream.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.