These Filipino fishermen are protecting endangered sharks - and boosting their incomes

A whale shark approaches a feeder boat off the beach of Tan-awan, Oslob. Image: REUTERS/David Loh

A group of the world’s poorest fishermen are protecting endangered whale sharks from being finned alive at Oslob in the Philippines.

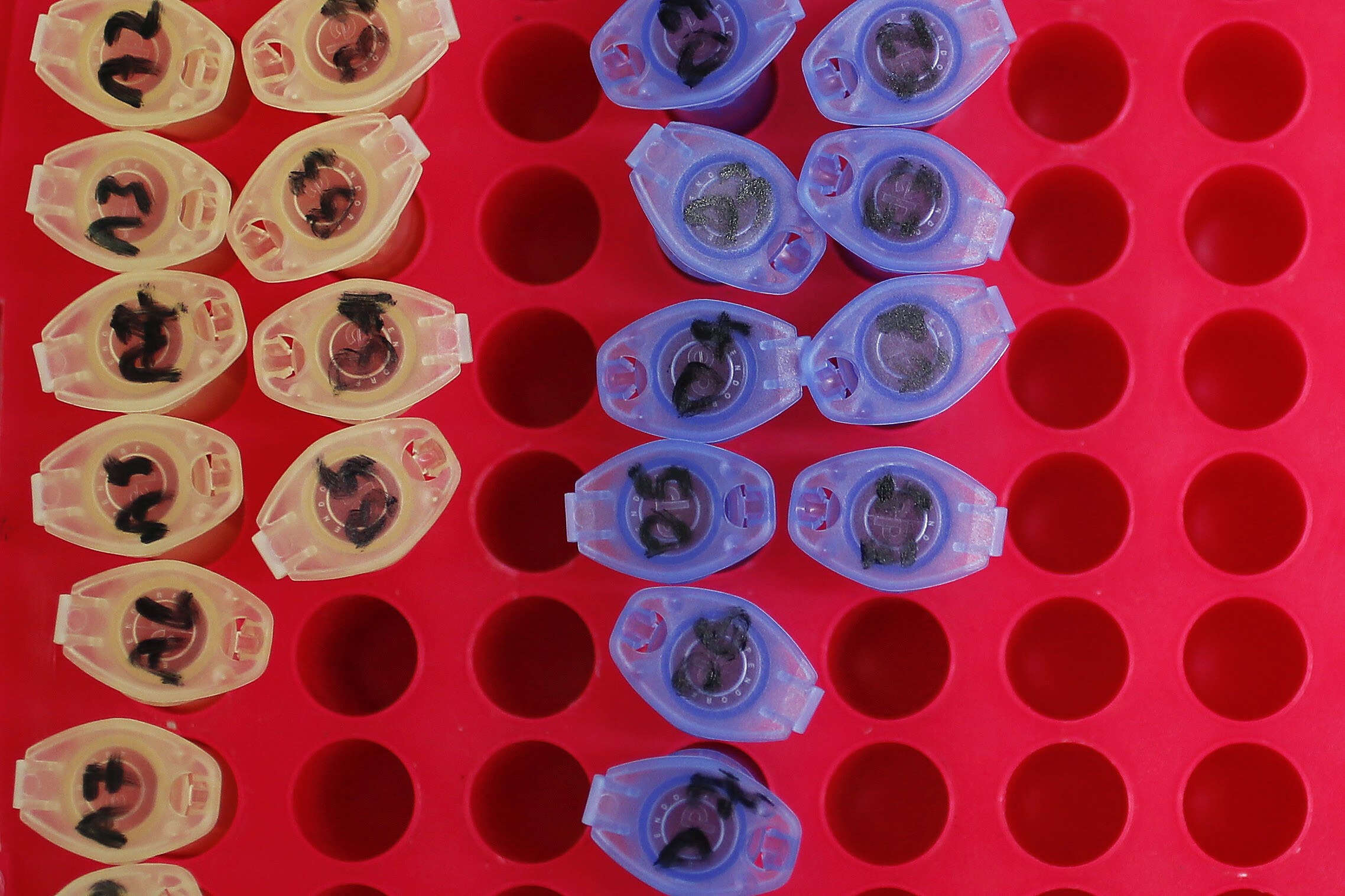

The fishermen have stopped fishing and turned to tourism, feeding whale sharks tiny amounts of krill to draw them closer to shore so tourists can snorkel or dive with them.

Oslob is the most reliable place in the world to swim with the massive fish. In calm waters, they come within 200m of the shore, and hundreds of thousands of tourists flock to see them. Former fishermen have gone from earning just a US$1.40 a day on average, to US$62 a day.

Our research involved investigating what effect the whale shark tourism has had on livelihoods and destructive fishing in the area. We found that Oslob is one of the world’s most surprising and successful alternative livelihood and conservation projects.

Destructive fishing

Illegal and destructive fishing, involving dynamite, cyanide, fish traps and drift gill nets, threatens endangered species and coral reefs throughout the Philippines.

Much of the rapidly growing population depend on fish as a key source of protein, and selling fish is an important part of many people’s income. As well as boats fishing illegally close to shore at night, fishermen use compressors and spears to dive for stingray, parrotfish and octopus. Even the smallest fish and crabs are taken. Catch is sold to tourist restaurants.

Despite legislation to protect whale sharks, they are still poached and finned alive, and caught as bycatch in trawl fisheries. “We have laws to protect whale sharks but they are still killed and slaughtered,” said the mayor of Oslob.

“Finning” is a particularly cruel practice: sharks’ fins are cut off and the shark is thrown back into the ocean, often alive, to die of suffocation. Fins are sold illegally to Taiwan for distribution in Southeast Asia. Big fins are highly prized for display outside shops and restaurants that sell shark fin products.

To protect the whale sharks on which people’s new tourism-based livelihoods depend, Oslob pays for sea patrols by volunteer sea wardens Bantay Dagat. Funding is also provided to manage five marine reserves and enforce fishery laws to stop destructive fishing along the 42km coastline. Villagers patrol the shore. “The enforcement of laws is very strict now,” said fisherman Bobong Lagaiho.

Destructive fishing has declined. Fish stocks and catch have increased and species such as mackerel are being caught for the first time in Tan-awan, the marine reserve where the whale sharks congregate.

The decline in destructive fishing, which in the Philippines can involve dynamite and cyanide, has also meant there are more non-endangered fish species for other fishers to catch.

Strong profits means strong conservation

The project in Oslob was designed by fishermen to provide an alternative to fishing at a time when they couldn’t catch enough to feed their families three meals a day, educate their children, or build houses strong enough to withstand typhoons.

“Now, our daughters go to school and we have concrete houses, so if there’s a typhoon we are no longer afraid. We are happy. We can treat our children to good food, unlike before,” said Carissa Jumaud, a fisherman’s wife.

Creating new forms of income is an essential part of reducing destructive fishing and overfishing in less developed countries. Conservation donors have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in various projects, however research has found they rarely work once funding and technical expertise are withdrawn and can even have negative effects. In one example, micro-loans to fishermen in Indonesia, designed to finance new businesses, were used instead to buy more fishing equipment.

In contrast, Oslob earned US$18.4 million from ticket sales between 2012 and 2016, with 751,046 visitors. Fishermen went from earning around US$512 a year to, on average, US$22,699 each.

Now, they only fish in their spare time. These incredible results are the driving force behind protecting whale sharks and coral reefs. “Once you protect our whale sharks, it follows that we an have obligation to protect our coral reefs because whale sharks are dependant on them,” said the mayor.

Feeding whale sharks is controversial, and some western environmentalists have lobbied to shut Oslob down. However, a recent review of various studies on Oslob found there is little robust evidence that feeding small amount of krill harms the whale sharks or significantly changes their behaviour.

Oslob is that rare thing that conservation donors strive to achieve – a sustainable livelihoods project that actually changes the behaviour of fishermen. Their work now protects whale sharks, reduces reliance on fishing for income, reduces destructive fishing, and increases fish stocks – all while lifting fishermen and their families out of poverty. Oslob is a win-win for fishermen, whale sharks and coral reefs.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Nature and Biodiversity

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.