The good news is the World Bank's list of the poorest countries thinned... but what now?

Emptier factories in Lesotho. It and other countries have benefitted from the stabilizing effects of global cooperation and trade. Image: REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

- The sharp reduction of economies classified ‘low income’ by the World Bank is encouraging, but points to difficult questions about the future.

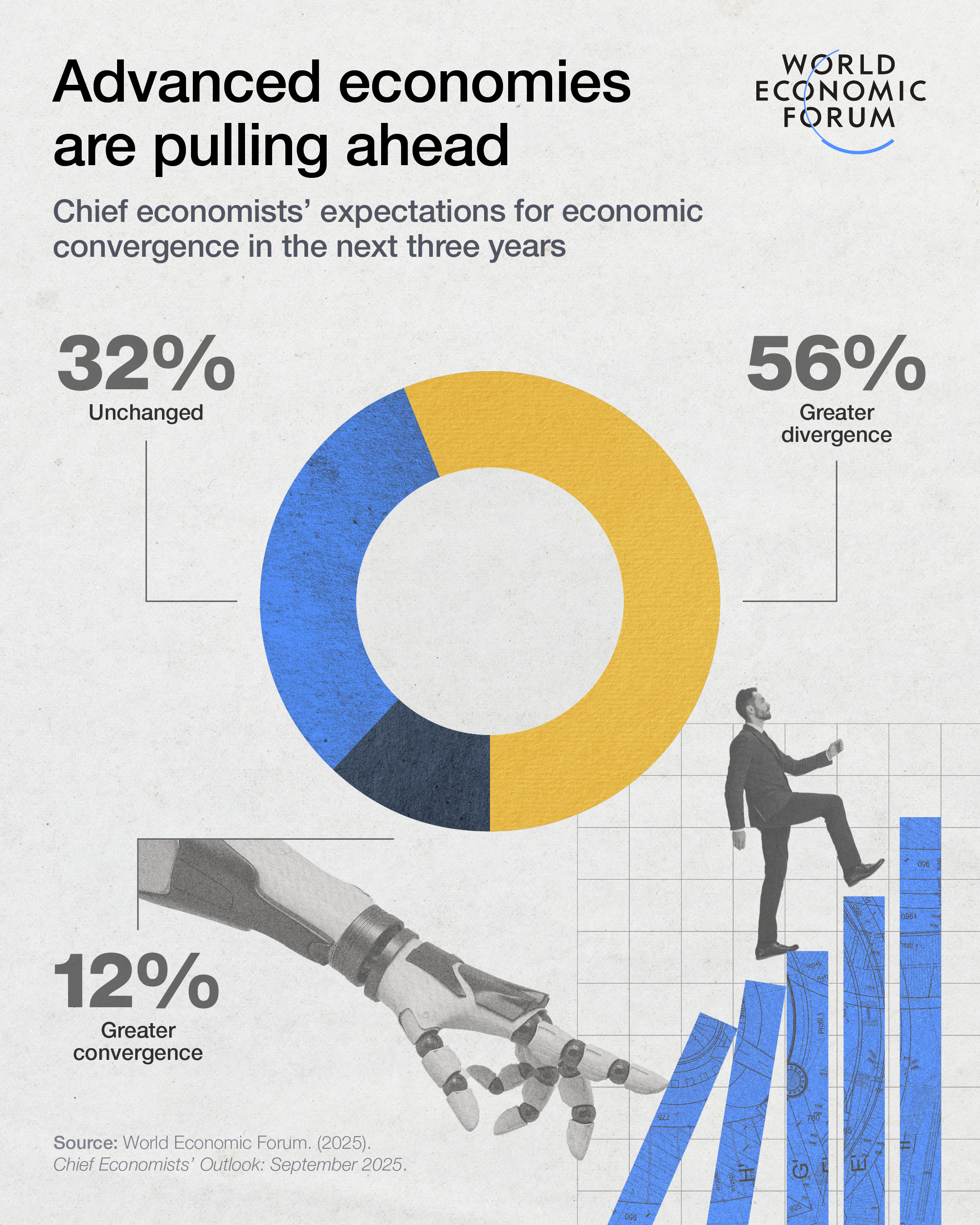

- Chief economists surveyed by the World Economic Forum now see a widening growth gap between developing countries and others.

- Building capacity in developing economies in uncertain times will be a topic of discussion at the upcoming World Bank and IMF Fall Meetings.

A lot can happen in 37 years.

If you’re Guyana, a South American nation where only about 70% of the population had access to electricity as recently as the 1990s, you might discover oil deposits so vast your economy rockets from among the poorest in the world into the ranks of the richest.

A longer and less-dramatic journey upward has been more typical. A wealth progression that benefits from development aid and a strategic embrace of globalization.

When the World Bank unveiled its most recent categorization of countries into four income groups not long ago it said that between 1987 and 2024, nearly half of those initially slotted into the bottom of that framework as "low income" had managed to advance higher.

That’s great news, but it points to a troubling question: Will the stabilizing effects of global cooperation and trade that elevated so many economies in the past remain available to others in the future?

Some top economists aren’t so sure.

More than half of the respondents surveyed for the World Economic Forum's latest Chief Economists' Outlook expect greater divergence between the growth of developing economies and their wealthier peers in the next few years, amid a backdrop of political instability, weakened institutions, and blunted global integration. To wit: They might not be able to gain ground like they used to.

That context is good reason to remain clear-eyed about the thinning of the World Bank’s “low income” ranks, and consider what comes next.

Gaining a higher classification is never a guarantee of smooth sailing, of course. And Guyana’s trip from “low income” to “high income” in two and a half decades may have followed years of intensive resource exploration, but it also benefitted from a healthy dose of good luck – though that’s the opposite of how some have characterized its blockbuster oil strike.

China’s own dizzying passage from “low Income” to “upper-middle income” in just a dozen years required less time than the average lifespan of a poodle. The country may be the most prominent model for the benefits of embracing global trade. It’s now the world’s biggest exporter by far, with a footprint so large that the punitive tariffs and systemic trade uncertainty emanating from the US have mostly nudged its presence in new directions, rather than depleting it in any meaningful way.

From ‘good’ jeans to ‘bad’ jeans

And then there’s Lesotho.

The Southern African nation of about 2 million people managed to graduate from the World Bank’s “low income” group in 2005. By that point it had secured a unique niche in global trade by by exporting 26 million pairs of jeans every year, almost entirely to the US.

That followed a flight of textile manufacturers to the country from heavily sanctioned, apartheid-era South Africa in the 1980s, and the enactment of the US African Growth and Opportunity Act in 2000 – legislation that enabled many goods from sub-Saharan Africa to enter duty-free. The AGOA was due to expire this month. Tariffs enacted by the White House have have already effectively cancelled it.

Lesotho was singled out with a 50% US tariff in April. Suddenly, importing all those jeans to sell to Americans would mean having to first fork over a significant portion of their declared value to the American government. The sky-high tariff rate was later reduced, but not before Lesotho was hit with order cancellations and thousands of layoffs.

As its manufacturing base falters, Lesotho is also dealing with a sharp reduction in foreign aid. That’s undermined local HIV-prevention efforts. In July, the country declared a national state of disaster.

It’s now experiencing a combined reversal of things cited by the World Bank as essential complements to sustained growth in developing countries: Integration into the global economy, and support from international organizations.

The World Bank’s income classifications are updated every July. They’re based on countries’ yearly Gross National Income per capita; $1,136 is the most recent threshold necessary to move from “low income” to “lower-middle income” (by way of comparison, America’s most recent annual GNI per capita was $83,660). As a US dollar-defined system it isn't perfect. Elevation into a new group reflects real changes in income, but maybe also shifting exchange rates.

The system has also excluded some significant economies over the years. When it launched in 1987, the Soviet Union and satellite states like Ukraine and Belarus were still reporting income figures in Marxist equivalents that didn’t jibe with its methodology.

Crucial aspects of the quality of income progression still aren’t necessarily being captured. More people may be earning more money, but how is that being experienced?

Bangladesh graduated from the “low income” group in 2014, as the country enjoyed a boom in textile and apparel manufacturing that’s been called miraculous. It has also grappled with business-related human rights issues and political instability.

Chile never found itself among the “low income” countries, but it wielded its own natural resources and a batch of free-trade deals to move from “lower-middle income” in 1987 to “high income” by 2012. Less than a decade later, social upheaval spurred an ultimately fruitless effort to rewrite the country's constitution. More recently its biggest export, copper, was threatened by US tariffs.

The legality of duties like that may be decided soon. Meanwhile more clarity on new, re-routed patterns of global trade could be in the offing, and potentially new means to foster cooperation and spur growth where it’s needed most – in ways that transcend labels.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Martin Jacob

February 17, 2026