Beyond the bean: Building a resilient cocoa future through complementary supply chains

The cocoa supply chain needs to be reinvented to help producers and the environment. Image: Chiara Cecchini

- Global demand for cocoa products is rising rapidly.

- More than 90% of global production comes from up to 6 million smallholder farms, the base of a supply chain dominated by a handful of multinational processors and confectionery brands.

- Complementary supply chains, through climate‑smart farming, fermentation‑based chocolate or cell‑cultured cocoa, offer a path to reduce deforestation, diversify supply and stabilize prices.

Chocolate and cocoa products deliver pleasure to billions of people, but the supply chain that brings this luxury to our tables is under pressure. Worldwide demand for chocolate is growing: the global market for chocolate products was worth roughly $123 billion in 2024 and is forecast to exceed $184 billion by 2033. Yet, this growth is built on a fragile foundation. Two West African nations, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, produce around 60% of the world’s cocoa beans and more than 90% of global production comes from up to 6 million smallholder farms, the base of a supply chain dominated by a handful of multinational processors and confectionery brands.

The story of cocoa and its challenges

A botanical primer

Cocoa trees (theobroma cacao) are small tropical evergreens that thrive in warm, humid climates and acidic, well‑drained soil. They produce colourful pods containing 30–50 seeds surrounded by a sweet pulp. After harvest, the beans and pulp are fermented for several days, transforming bitterness into the complex flavours prized in chocolate. On average, each pod yields about 40–50 grams of dried beans, which can be separated into roughly equal parts of cocoa butter and cocoa solids.

A concentrated supply chain

Because cocoa grows best in forested or formerly forested areas, farmers have often cleared new land to plant trees. This expansion has made cocoa a major driver of deforestation in West Africa, leading to soil degradation, water insecurity and crop failures. Deforestation-linked cocoa also threatens biodiversity hotspots in Sub‑Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Although most cocoa comes from smallholders, processing and export are dominated by a few traders and grinders.

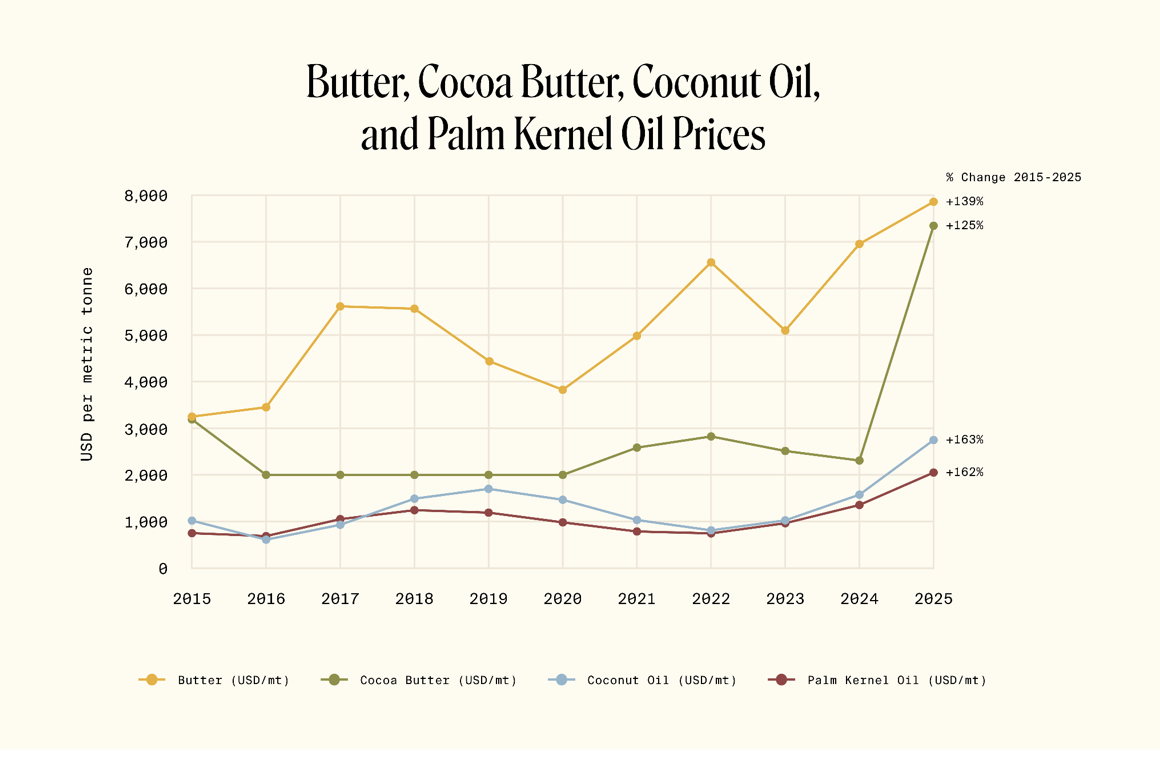

This concentration means that while the farmers bear the environmental impact, they have limited bargaining power and often lack access to financing or training to adopt sustainable practices. Recent cocoa price spikes — prices more than doubled between mid‑2022 and early 2024 — highlight how supply shocks reverberate through the market.

Climate and ethical pressures

Cocoa is sensitive to changes in rainfall and temperature. Unpredictable weather associated with climate change has reduced yields in key regions, while pests and diseases, such as cacao swollen‑shoot virus, continue to spread. And, the industry also struggles with allegations of child labour and poor wages. Sustainability certifications have improved transparency, yet global demand keeps pushing into previously untouched forests.

Why the current model is hard to sustain

Deforestation and biodiversity loss

Cocoa’s expansion into forests is driven by the quest for higher yields and incomes. Cocoa's role in unsustainable land use has been widely studied. Deforestation leads to soil exhaustion, reduced rainfall and a loss of pollinators and wildlife. Protecting primary and secondary forests is, therefore, one of the key principles of sustainable cocoa, but with increasing demand, this is becoming harder.

Smallholders under pressure

Most farmers lack the capital to invest in improved seedlings, irrigation or fertilizers. They also face ageing trees and pests that reduce productivity. Without support, many continue to clear new land to maintain yields, perpetuating the deforestation cycle.

Concentration risk

The global cocoa value chain is structurally imbalanced. Millions of smallholder farmers — most cultivating less than 5 hectares — form the base of the supply pyramid. Yet upstream, a few multinational corporations dominate the purchasing, processing and distribution of cocoa products (the main ones being Mars, Cargill, Barry Callebaut, Mondelez, Ferrero, Hershey, Lindt, Godiva and Nestlé). This many-to-few relationship creates acute concentration risk. Price shocks, climate events or political instability in key producing countries ripple rapidly through the supply chain, influencing everything from bean prices in Ghana to chocolate bar prices in Europe.

Building complementarity

Diversifying supply sources is critical. Two approaches, sustainable intensification and alternative cocoa, offer some hope.

1. Sustainable intensification and agroforestry

Farmers can improve yields on existing land through climate‑smart practices: using shade trees to maintain humidity, intercropping cocoa with other crops and adopting disease‑resistant varieties. Certification initiatives, such as Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade, encourage these practices, but uptake remains limited. The World Bank’s deforestation‑free cocoa principles calls for protecting forests, ensuring legality, improving transparency, integrating sustainability into corporate strategies and operating at scale. Governments and buyers should provide premiums for verified deforestation‑free cocoa and invest in extension services, irrigation and pest management.

2. Cocoa-free innovation and complementary supply chains

Complementary supply chains are rapidly emerging alongside traditional cocoa, driven by biotechnology, fermentation and organic chemistry. A growing number of companies are rethinking chocolate from the ground up — reproducing its flavour, texture and fat profile without relying on tropical beans.

Several companies are leveraging fermentation and upcycled ingredients to recreate the sensory experience of cocoa. For instance, Voyage Foods, Win-Win and Planet A Foods use substrates like oats, sunflower flour and carob to deliver cocoa-like taste with significantly lower emissions. Others, such as Celleste Bio and California Cultured, are advancing cell-cultured cocoa, growing real cocoa cells in bioreactors under controlled conditions. A third wave is exploring structured fats production that mimics cocoa butter, a key functional component of chocolate.

These innovations are not positioned to replace premium, single-origin chocolate in the short term. They offer scalable, complementary options for mass-market applications — coatings, fillings and industrial formulations — where volume demand is highest and environmental impact most acute. Together with sustainable farming, these approaches diversify sourcing, relieve pressure on tropical forests and build resilience into a fragile value chain.

Looking at business models

Ensuring farmers are beneficiaries of the transition to sustainable cocoa — not its collateral — requires moving beyond short-term sourcing arrangements towards systemic business model redesign. Four shifts stand out:

1. Align incentives through value-sharing

Traditional spot markets offer little predictability or upside to growers. Instead, long-term sourcing contracts paired with revenue-sharing or premium guarantees can align incentives across the value chain. These models offer farmers a stable income, which justifies investment in replanting, soil health and climate-resilient practices.

2. Shift from supply chains to value networks

Empowering farmers as co-owners — through cooperatives, shared processing infrastructure or local equity stakes — can rebalance bargaining power. New entrants building alternative cocoa infrastructure in origin regions should consider inclusive ownership models to avoid reproducing extractive dynamics.

3. Leverage blended finance and ecosystem services

Unlocking capital for sustainable farming requires creative financial tools. Blended finance can de-risk smallholder investment, while carbon payments and biodiversity credits help internalize the value of avoided deforestation. Programmes, like the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, are pioneering this approach in cocoa-growing landscapes.

4. Invest in farmer capability, not just compliance

Beyond certification, farmers need access to quality inputs, disease-resistant seedlings and agronomic know-how. Scalable delivery mechanisms, such as mobile agronomy apps, bundled insurance and decentralized training, can enable the adoption of climate-smart practices and reduce land expansion pressure.

A shared responsibility for a sustainable cocoa future

Cocoa’s challenges cannot be solved by one single party. Governments must enforce forest protection and support rural infrastructure; companies must commit to traceable, deforestation‑free cocoa and invest in alternative supply chains; consumers must be supported in evolving their perception around chocolate and confectionery, moving to a more premium and sustainable idea of chocolate.

Complementary supply chains, through climate‑smart farming, fermentation‑based chocolate or cell‑cultured cocoa, offer a path to reduce deforestation, diversify supply and stabilize prices. When paired with inclusive business models that put landowners and farmers at the centre, these innovations can ensure that the cocoa industry continues to delight consumers without costing the Earth.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Forests

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

Emily Farnworth and Alice Ruhweza

March 12, 2026