How ‘crocodile economics’ is proving growth and climate action can thrive together

“Crocodile economics” shows growth and climate progress can occur. Image: REUTERS/Stringer

- “Crocodile economics” describes the moment when a country’s gross domestic product keeps rising while its emissions fall — the two curves diverging like a crocodile’s open jaws.

- Forty-nine countries have already decoupled economic growth from fossil fuels, driven by cheaper renewables, electric vehicles and shifts in energy systems.

- Emerging economies can skip carbon-intensive development altogether by leveraging today’s affordable clean technologies.

As world leaders converge on Belém, Brazil, in November for this year’s climate summit, the pressure to accelerate action has never been more acute. Just in October, scientists reported that the world may have crossed the first climate tipping point – warm-water coral reefs – and others are on the brink.

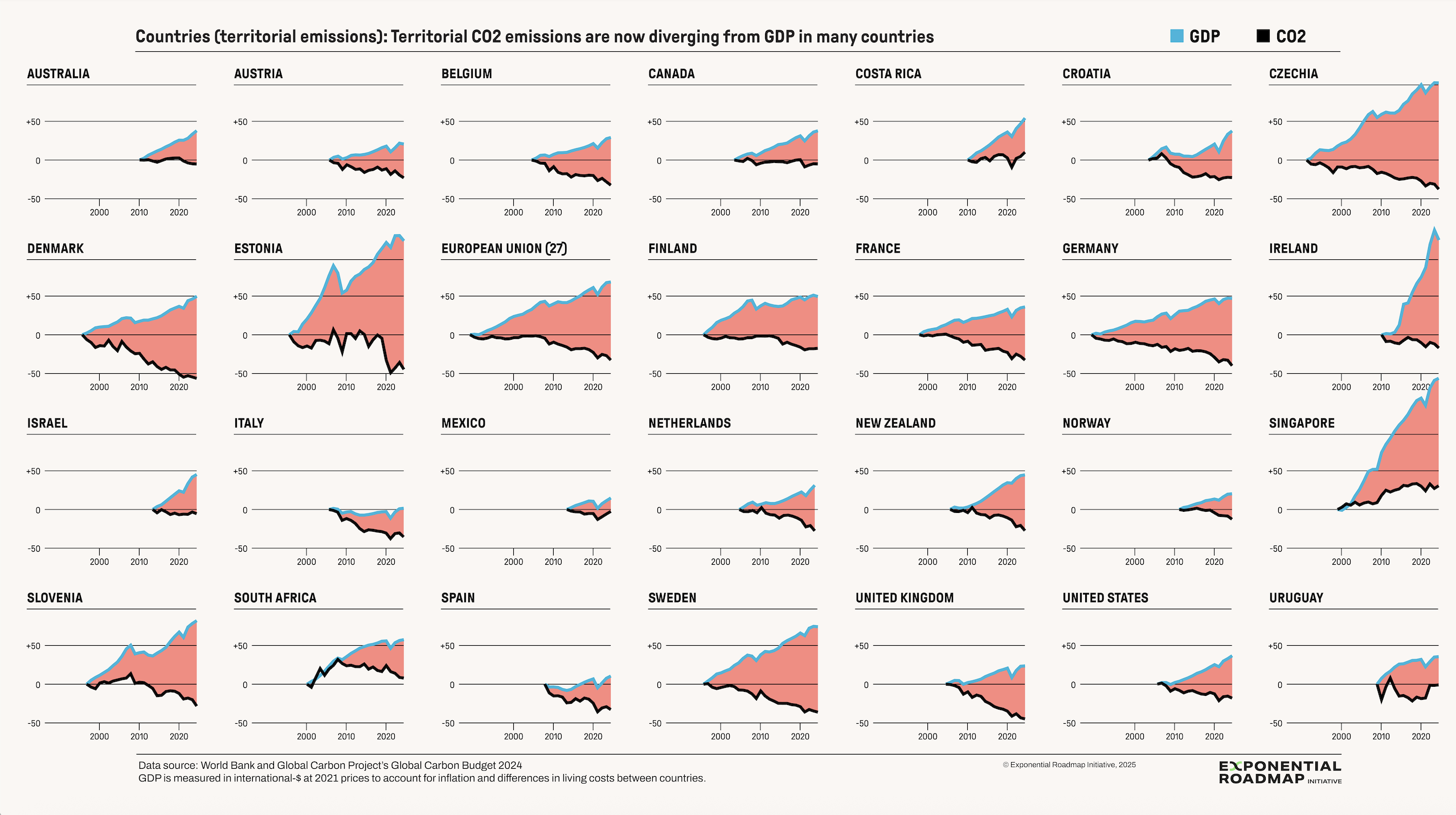

Many are concerned that the world is making no progress. While we have not yet reached peak emissions, the data tells a story of remarkable transformation. A new economic model is unfolding – across dozens of countries, gross domestic product (GDP) is rising while emissions are falling, like the jaws of a crocodile opening.

We call this “crocodile economics” and as we articulate in a new report, it represents a profound shift in the global economy.

Since the Industrial Revolution began, economic growth has risen in tandem with the use of fossil fuels. However, this is no longer true for many countries.

Our new data shows the point at which economies first made substantial progress in reducing the link between growth and fossil fuels – in some countries, this occurred 25 years ago, representing one quarter of a century of progress. Overall, 49 countries have decoupled, primarily in Europe and Oceania – one-quarter of the world – according to a separate 2024 analysis.

A growing pattern

In 2023, net greenhouse-gas emissions in the EU were 37% below 1990 levels, while GDP was approximately 70% higher. The European Environment Agency reported a 9% drop in EU emissions in 2023 alone, primarily driven by the power sector, where emissions decreased by 22%.

The UK exhibits a similar pattern: in 2023, emissions were around 54% below the 1990 level, while GDP grew by around 84%. In September 2024, the country's last coal-fired power station closed.

However, we must guard against undue optimism. Ireland, for example, has experienced rapid economic growth, while emissions have stabilised; however, this is largely a result of large technology companies routing significant profits through the country in recent years.

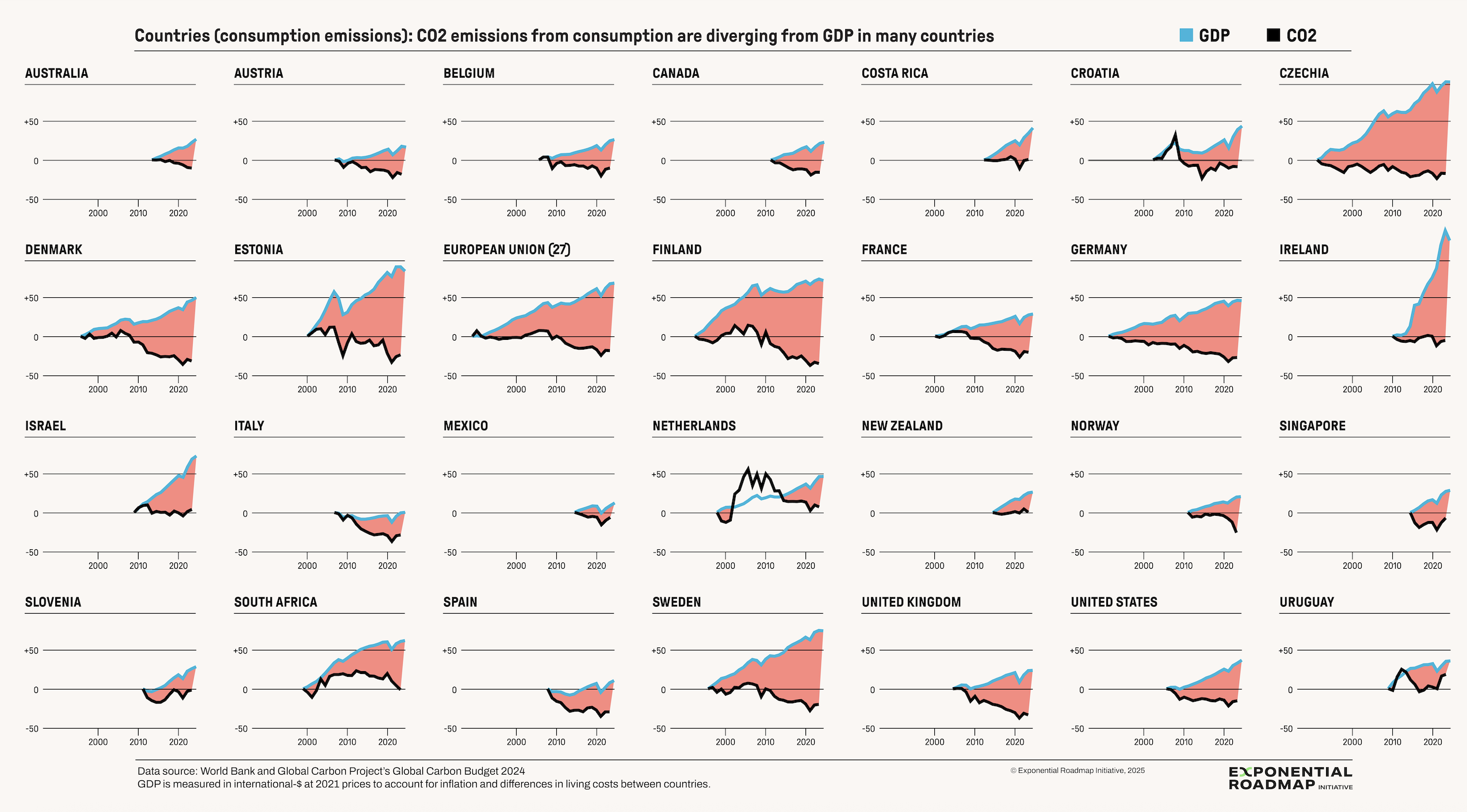

Crocodile economics is not only confined to territorial emissions (emissions produced within a country): we can also see a similar pattern in consumption emissions, which include a country’s emissions from imported goods from overseas.

Slow progress to exponential change

Despite the relative progress, emissions reductions still fall far short of the rates required to meet the most stringent climate targets of the Paris Agreement, which aim to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

One analysis concludes that, on recent progress, countries would, on average, take more than 220 years to reduce their emissions by 95%.

The crocodiles need to open their jaws much wider. However, we must remember that this progress has emerged over three decades, during which key technologies such as wind and solar were more expensive than fossil fuels and electric vehicles were only beginning to scale as viable alternatives to internal combustion engines.

For both energy and transport, prices are falling exponentially. Solar energy is now the cheapest electricity source in history – a milestone passed in 2020. Electric vehicles are dropping in price and with the right incentives, they can outcompete internal combustion engines in many places.

Leapfrogging towards crocodile economics

The next wave of crocodile economics will likely spread faster than the first.

Some countries will take more time to become crocodile economies. For least-developed nations with historically tiny emissions, justice and fairness principles must apply. Bringing these countries out of poverty must be a priority even if emissions initially rise.

The key will be to leapfrog traditional development pathways that have been rooted in coal and oil, thereby avoiding the lock-in of fossil fuels.

China, whose economy accounts for a significant portion of global greenhouse gas emissions, saw emissions decline by approximately 1% over the 12 months to Quarter 1 in 2025, as new wind, solar and nuclear additions outpaced demand growth. This may signal that a new crocodile is on the horizon.

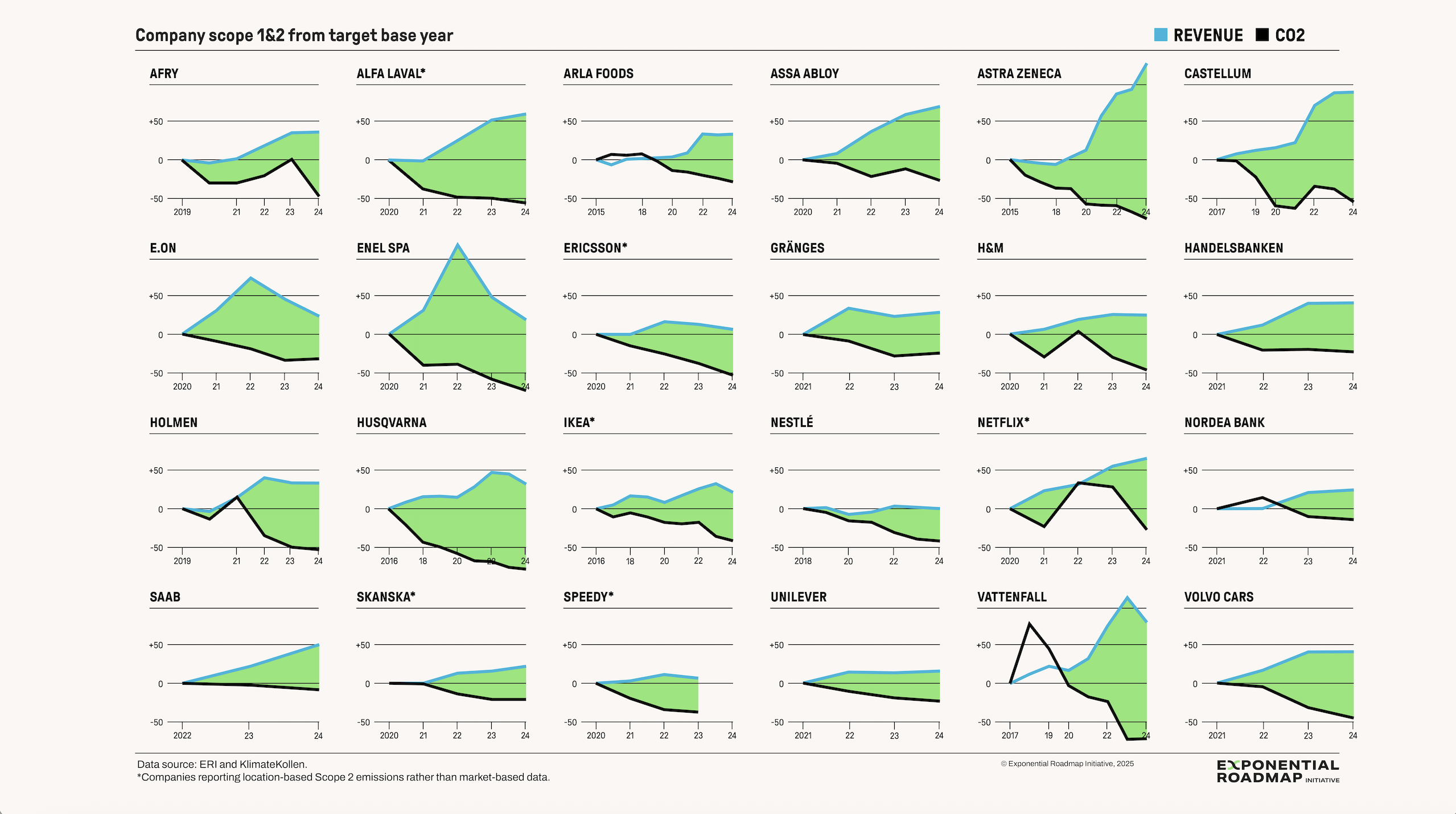

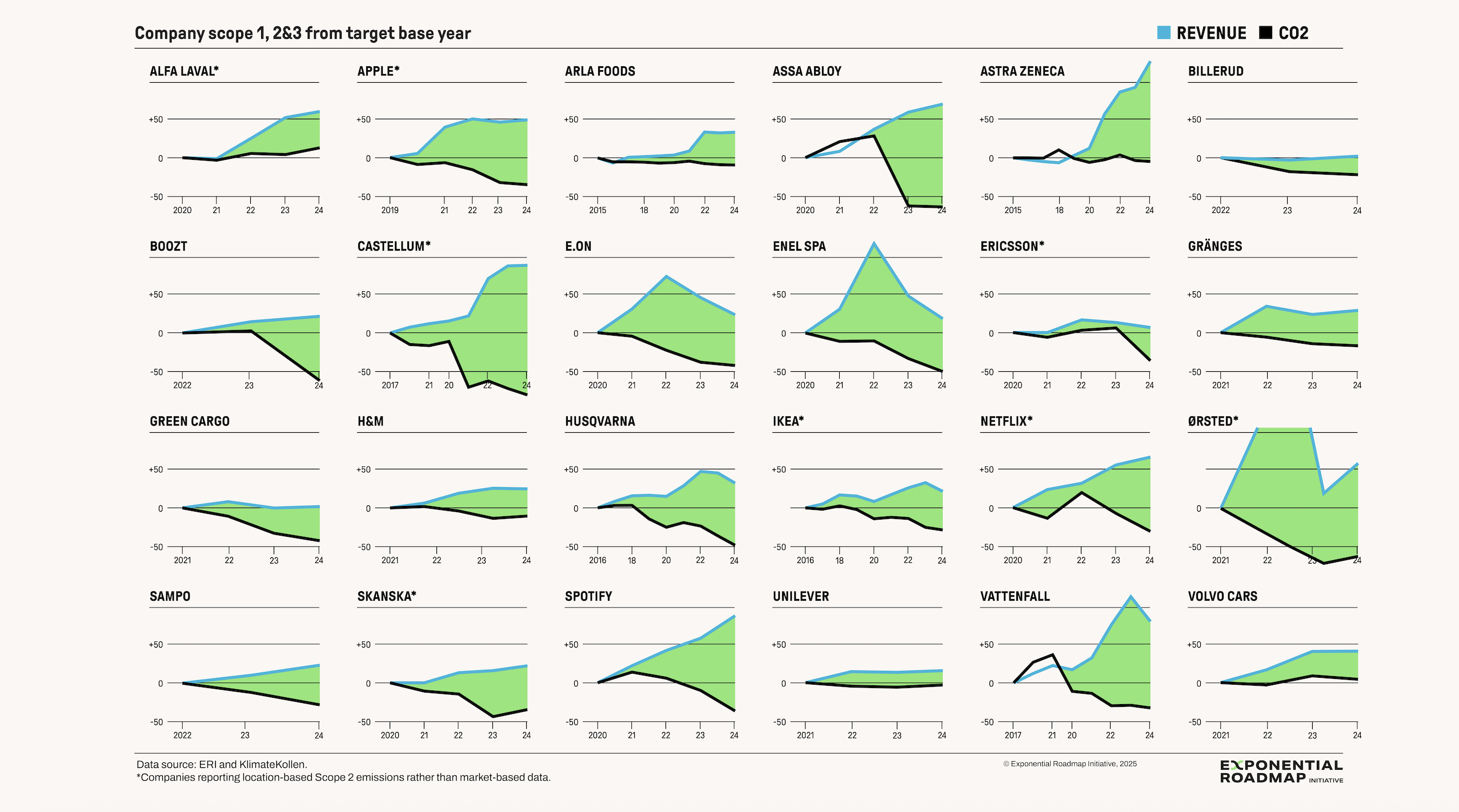

As countries transform, companies are also adopting crocodile economics, albeit with a shorter time series, greater variability and more significant caveats.

Companies join the crocodile economy

As shown below, 24 companies are decoupling Scope 1 and 2 emissions (emissions from sources a company owns and controls and emissions from purchasing electricity) from revenue.

Even Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions are decoupling (Scope 3 being emissions generated from the supply chain). The companies selected represent a broad range of industries: energy, technology, entertainment, industry, fashion, banking, furniture, food and consumables.

However, this is still early days.

Some companies exhibit absolute decoupling, while others exhibit relative decoupling. Due to data availability, we focused largely on Swedish firms. As we expand the analysis, we will widen the net to include more companies beyond Sweden.

COP30 must accelerate the crocodile revolution

As delegates gather in Belém, Brazil, for COP30, the crocodiles shown here represent a significant economic revolution. This first wave of countries and companies have done the heavy lifting: de-risking technologies, building supply chains and demonstrating viable pathways.

Now, as Chinese manufacturing delivers solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles at unprecedented prices, the barrier to entry for new crocodiles has collapsed. Countries that follow will not need decades to decouple – their transitions can be dramatically faster.

The implications for COP30 are clear: we are no longer debating whether economic transformation is possible – we are witnessing it unfold at different speeds across the global economy. Ignore this trend and it may come back to bite you.

Johan Falk, CEO, Exponential Roadmap Initiative, also contributed to this article.

* Note on data: GDP and carbon data (1990–2023) from the World Bank and the Global Carbon Budget respectively, as compiled by Our World in Data. GDP was adjusted for inflation using international dollars at 2021 prices. The analysis was inspired by John Burn-Murdoch’s article, “Economics may take us to net zero all on its own”, Financial Times (2022).

For the company-level decoupling analysis, we selected data collected by Klimatkollen and Exponential Roadmap Initiative with a skew towards Swedish companies. Revenue data are as reported by companies and not adjusted for inflation.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Geo-economics

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

Moattar Samim

February 21, 2026