Too offbeat to automate? Here's a reason economies still need more people, not less

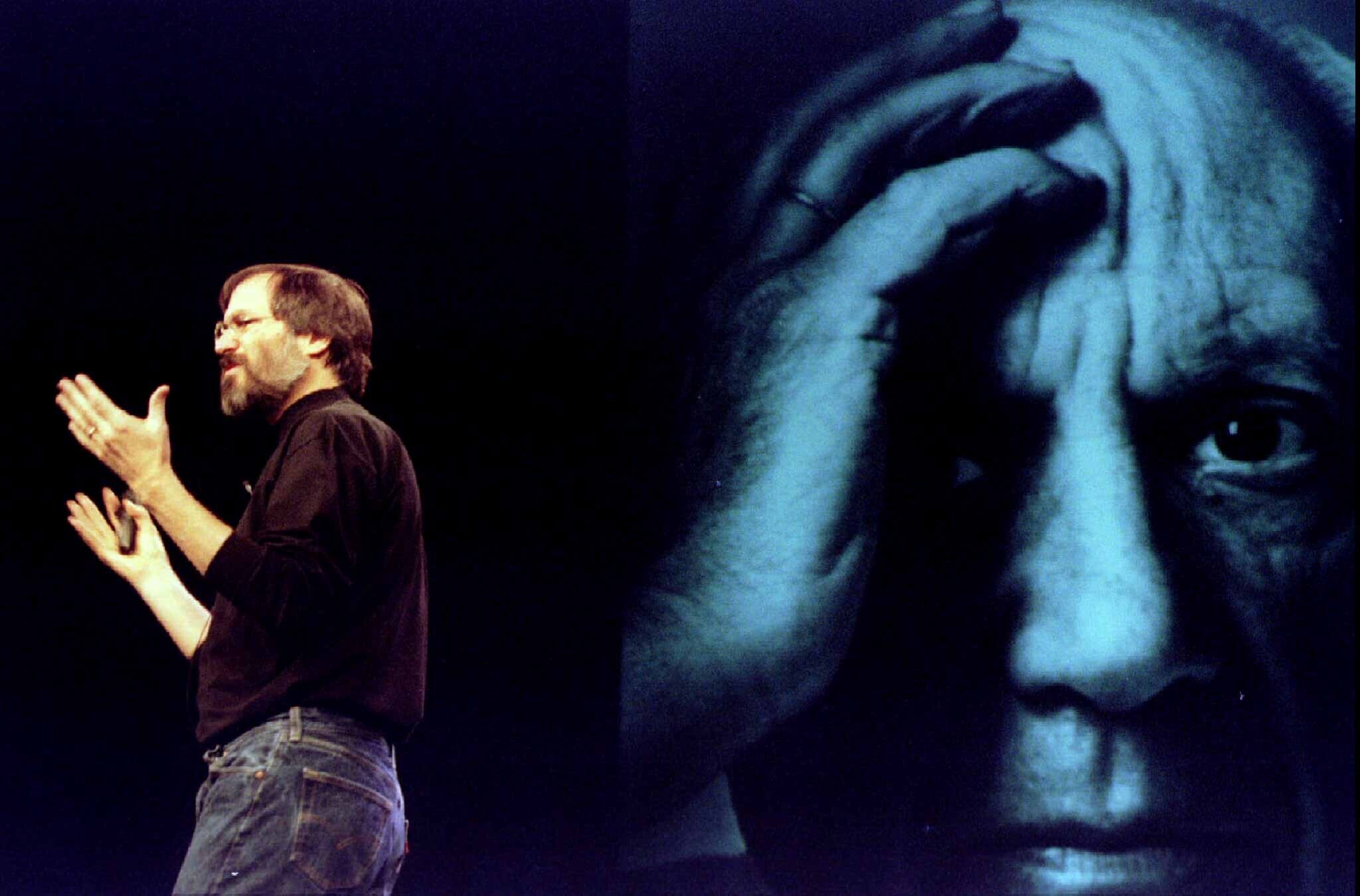

More varieties of Einstein needed; people remain a crucial source of the creative ideas big and small that boost economies. Image: REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

- News stories about AI-related job cuts and hiring slowdowns are proliferating.

- But there’s at least one thing economic growth still relies on humans for: Big ideas. Efforts to automate the output of history’s most far-out thinkers may only underline the limits of chips, data and algorithms.

- Soft skills like creative thinking are now the 'hard currency' of the AI-era job market, according to a new World Economic Forum report.

Hennig Brand just woke up one day and thought, why not boil urine?

Possibly. It’s impossible to know the 17th-century German alchemist’s exact thinking as he began distilling discharge in his basement lab for experiments that eventually led to the discovery of phosphorus and, in some ways, the dawn of modern chemistry.

Clean drinking water, penicillin and the pharmaceutical industry would follow.

The blend of genius and quirk that compelled Brand to take that scientific detour is the kind of thing economies will likely always require, even as artificial intelligence (AI) proliferates. A pair of recent studies pointed to the enduring value of human creativity in the AI era; each suggests the technology still relies heavily on the quality of the grey matter prompting it. A more recent World Economic Forum report describes soft skills like creativity as the new "hard currency" of the job market.

That’s worth noting amid relentless headlines about people being cut out of economies, as the promise of AI triggers hiring slowdowns and layoffs. In fact, the constant need for big ideas that can boost growth may require sizeable additions of people over time, thanks to the burden of knowledge (the more of it we have, the more challenging it becomes to come up with genuinely original concepts).

One thing seems clear about AI so far: it’s built to please, sometimes to a fault. Albert Einstein was not.

The theoretical physicist displayed what's been described as “a casual willingness to question authority.” He conjured up the theory of relativity not by following the rules of physics better than anyone else, but by ignoring them and writing new versions. A large language model trained on the sum-total of physics knowledge to that point would never have managed the same thing.

Of course, somewhere on the murky horizon there’s a point where AI may also start writing its own rules. A former Google CEO predicted systems intellectually on par with top scientists by the end of this decade. OpenAI’s current CEO said it might only be a couple of years before AI is making discoveries that humans can’t match.

Have you read?

To authentically automate the biggest ideas, would that first require engineering the seemingly inevitable eccentricities of the biggest thinkers? The symptoms of exceptional minds that are also (so far, anyway) uniquely human traits?

An artificial Einstein might require the algorithmic equivalent of struggling with math during university studies, adopting curious habits (“socks not worn by” gets three citations in one biography’s index), and taking a low-level job at a patent office that leaves ample time for side hustles like lecturing to mostly empty rooms, as well as playing a lot of violin while formulating a theory that’s since been credited with changing everything.

At first, Einstein’s theory of relativity mostly confused a lot of people. Since then, it’s helped a lot of other people find their way around by making GPS systems possible. Other inventions credited to him, at least in part, include lasers and solar cells.

Air baths, exotic animals and carrot diets

Benjamin Franklin invented the lightning rod and bifocals. In the summer of 1752, the American polymath walked directly into a nasty storm with a kite to hoist a metal key in the direction of thunder clouds; an early concept for the electric battery was one result of his experiments. Franklin also sat in the cold au naturel every morning for his daily air bath.

The list goes on: Darwin had a thing for devouring exotic animals from armadillos to pumas; Isaac Newton jabbed a needle into his eye socket to see if it altered perception; Thomas Edison made job applicants at his New Jersey-based industrial conglomerate answer questions like “Who composed ‘Il Trovatore’?”

There are signs quirk like that may in fact be programmable. Generative AI has been composing disarmingly vivid music and poetry. And the technology has demonstrated unique strategic thought that transcends typical human approaches to doing things like playing a board game.

For now, at least, it’s relatively basic types of knowledge work that are being sized up for automation. Walmart, the big-box retailer and largest private employer in the US, recently disclosed plans to keep its employee headcount flat for the next few years. A recent UK-based study cited a “job-pocalypse” for entry-level positions in particular. Assumptions about white-collar redundancy are clearly shaping business plans.

Probably not all of those assumptions will be realized. Radiologists are still hanging in there, for example, years after experts singled them out as highly likely for replacement.

Replacing the most unique thinkers might first require nailing down exactly what it is that makes some people more creative than others. A study published in 2018 pointed to fundamental wiring – highly creative people, it found, tend to have minds capable of co-activating brain networks that normally fire up one at a time.

There may well be links between brain wiring and behaviour like eating nothing but carrots for weeks on end, which is something Steve Jobs would occasionally do.

Jobs, the American co-founder and CEO of Apple, showcased the benefits of expanding the idea pool by accessing a greater number of people. His biological father had been a Syrian immigrant, a fact memorialized in a Banksy art installation.

Jobs was considered a singular genius. But he needed other contributors of smaller ideas that latticed up to monumental concepts. Teams of creative thinkers were necessary to design things like a reliable software keyboard before the first iPhone could become a reality. “He didn’t micromanage,” an engineer assigned to the project said of his former boss.

The enduring need for human inspiration may bode well for places with booming populations and young people relatively unburdened by risk aversion. Africa fits that bill nicely, the environmental economist Andrew Steer noted during a recent World Economic Forum event.

Identifying exactly how those young people might bring ideas to the table that translate into dramatic economic growth is difficult. But it would likely involve more than reading words in textbooks or scraping figures from websites. “Consciousness is much richer than both mathematics and computations,” as one academic article put it.

Patience can be required with the personality types capable of quickening progress. Payoffs can take a while.

Carl Auer von Welsbach was among the handful of scientists to initially figure out how to separate rare earth elements and turn them into marketable products. Rare earths are now required for seemingly just about everything a country might need to develop cutting-edge technology and defend itself. Von Welsbach’s first foray was a streetlight company that failed.

Hennig Brand had his own foibles. He began boiling urine in his basement not in pursuit of phosphorus, but because he was trying to make gold. Some of the motivation driving his genius was presumably good old-fashioned greed.

Which might be one of the most glaringly human traits of all.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Shantanu Srivastava and Tanya Rana

March 5, 2026