Want to invest in Africa? It's time to think smaller and smarter

The stability of African economies depends on the financial resilience of the region’s roughly 44 million formal SMMEs Image: REUTERS/Mike Hutchings

- In Africa, SMMEs account for more than 90% of registered businesses and carry roughly 80% of the labour force.

- Traditional lending frameworks were built around large corporates and asset-backed borrowers, contributing to a significant SMME funding gap in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Systems, technology, governance and training must convene to create a system in which micro and small enterprises can graduate into the middle of the market where sustainable development gains are generated.

In Africa’s largest economy, South Africa, just 38% of small businesses believe they can survive more than a year under current cost pressures without external support.

With more than two million SMMEs (small, medium and micro enterprises) operating in the country, the figure is a striking indication of how thin the margins of endurance have become for the entrepreneurs that make up the bulk of South Africa’s economic base.

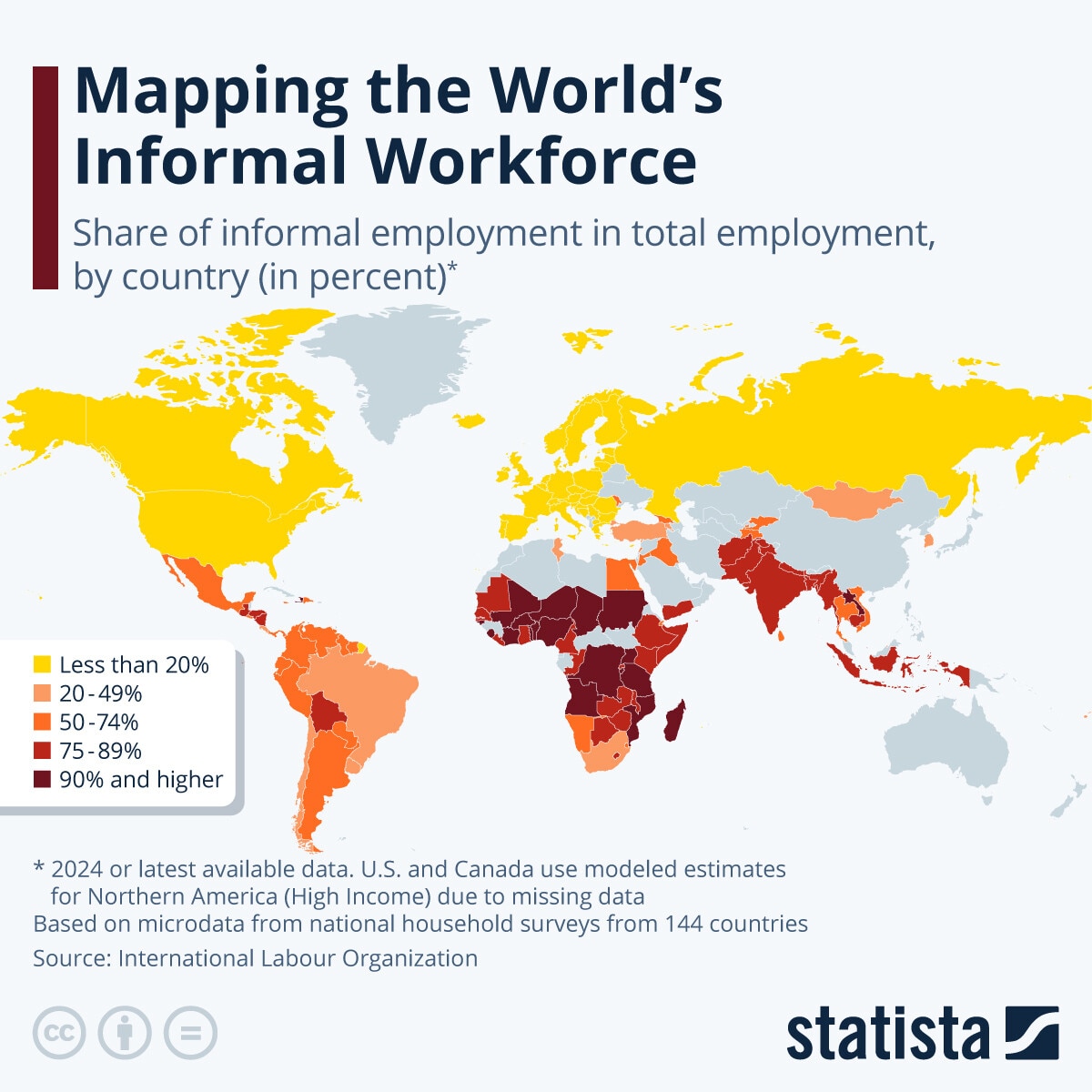

A similar pattern holds across the continent, where SMMEs account for more than 90% of registered businesses and carry roughly 80% of the labour force. The stability of African economies depends less on the performance of large corporates than on the financial resilience of the region’s roughly 44 million formal SMMEs – a number that rises far higher once informal enterprises are accounted for, many of which operate on constrained balance sheets.

Some parts of this base generate considerable activity even without formal support. Conservative estimates place the value of South Africa’s township economy, for example, at close to R1 trillion a year (approximately $59.8 billion). This is largely driven by informal retail and service businesses that compete on proximity, convenience and deep local demand, despite being largely unregistered. The same can be said for the country’s gig economy, where roughly half of employed adults are believed to earn from a secondary source or informal side hustle, reflecting a broader continental trend in which irregular income forms a material share of economic life.

The scale of this activity, however, should not be mistaken for success, but is rather a sign of how much economic potential remains outside formal structures and how critical it is to build pathways that help these entrepreneurs scale their businesses.

Many argue that the single biggest impediment to the growth of the sector is access to finance, because financial institutions often view these businesses as costly and risky to serve – a dynamic that is one contributor to an SMME funding gap in sub-Saharan Africa estimated at roughly $331 billion. The effects are even more pronounced for women-led and youth-owned enterprises, which frequently face additional hurdles owing to entrenched biases and perceived risks.

But this is all indicative of a symptom rather than the underlying systemic factors that turn those gaps into structural constraints.

Smaller enterprises often operate with limited financial records, inadequate business plans, irregular cash flows and few assets against which lenders can secure, yet these are the very signals the financial system uses to evaluate risk. Traditional lending frameworks were built around large corporates and asset-backed borrowers, which means the tools used to assess creditworthiness assume a level of formality and predictability that smaller businesses struggle to demonstrate.

The financial sector has started to adapt, helped by digital tools, emerging AI technologies and new data streams that broaden the information available to assess smaller businesses and their needs.

It is worth remembering that much of Africa’s entrepreneurial activity emerges from necessity rather than choice. People move between personal income-generating work, side ventures, and early forms of enterprise with few clear boundaries, and the constraints they face in their own financial lives often carry into their businesses. Many begin trading without the knowledge or support that would help them manage cashflow or navigate basic supply-chain decisions, for example. This is why efforts to widen financial inclusion at the individual level sit so close to the task of strengthening small enterprises.

Financial services have been building this foundation through practical training programmes and digital tools that help people organize their finances with more confidence. What changes with AI is the possibility of support that adjusts to each customer’s circumstances rather than offering standardized guidance.

Another priority has been to open clearer pathways to market. E-commerce adoption across the continent has pushed more trading activity online, and banks have had to build the payment and settlement rails that allow smaller enterprises to participate in these channels with fewer barriers.

Several institutions have also backed digital platforms that link smaller enterprises to buyers, inputs and distribution channels, allowing them to participate in supply chains that were previously out of reach. The imperative is to expand these market pathways across borders and connect more of Africa’s smaller enterprises to regional and global supply chains, because scale and continuity depend on being able to sell beyond the limits of immediate markets.

On the fundamental question of access to finance, there are signs of real improvement. There has been an uptake of AI systems that draw signals from big data and predictive analytics across payments activity, supply-chain transactions, tax records, mobile-money flows and digital-platform interactions. This builds a behavioural picture of enterprise performance that reflects how a small business actually operates.

As these datasets converge, lenders can develop hyper-personalized approaches to products and services. This is already producing more flexible credit and working-finance solutions for businesses that have struggled to meet traditional requirements.

Technology, however, is not a silver bullet. The challenges facing African SMMEs are complex and the financial sector cannot resolve them on its own.

Governments set the policy environment in which these businesses operate and meaningful progress depends on coordination between banks, public institutions and development partners. It is also about creating conditions that can ignite entrepreneurial spirit in practical ways, so that more people see enterprise as a viable path and not just a response to constraint.

The broader aim is to create a system in which micro and small enterprises can graduate into the middle of the market, because that is where sustainable development gains are generated. A deeper cohort of medium-sized firms strengthens supply chains, anchors more meaningful job creation and broadens the base of productive investment.

Thinking smaller and smarter, therefore, is not a shift in ambition but a shift in method to direct policy, capital, and technology toward the segment that already carries the weight of Africa’s economies and holds the greatest potential to shape their future trajectory.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Martin Jacob

February 17, 2026