Why London's children are being offered polio vaccine boosters

Children in London are being offered a polio vaccine booster. Image: Unsplash/CDC

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Health and Healthcare

- Following reports of poliovirus in sewage in London, a booster vaccine dose is being offered to children in the UK's capital.

- Poliomyelitis, or polio, is a devastating disease that has historically seen paralysis and death around the world, mainly in children.

- The only effective way to control spread of the virus is to ensure vaccine coverage is as high as possible.

- According to the JCVI, offering an additional dose to those who are vaccinated will boost antibody levels and may help to reduce asymptomatic shedding of the virus.

In June, the UK Health Security Agency reported that poliovirus had been detected in sewage in north and east London between February and May 2022.

Following this, people were advised to ensure their children were up to date with their polio vaccinations.

On August 10, the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) recommended that a further booster dose of polio vaccine be offered to all children in London aged between one and nine.

So what’s happened between June and now, and why this change in vaccination policy?

First, a bit of background. Poliomyelitis, or polio, is a devastating disease that has historically seen paralysis and death around the world, mainly in children. It’s caused by an RNA virus (poliovirus) that spreads easily from person to person, usually through virus shed in faeces.

The vast majority of infections with poliovirus actually go unnoticed, but a small proportion of those infected will develop paralysis (or paralytic poliomyelitis), which can lead to respiratory failure or long-term deformities.

In the 1950s, two polio vaccines were developed: a live attenuated vaccine administered orally (the Sabin vaccine), and an inactivated vaccine given by injection (the Salk vaccine). A live attenuated vaccine is based on a virus that’s still able to reproduce, but is weakened so it doesn’t cause disease. An inactivated vaccine, on the other hand, cannot reproduce.

Both vaccines are highly effective at preventing paralytic poliomyelitis. The oral vaccine in particular can induce strong immunity in the gut and so is better at reducing faecal shedding of the virus, and therefore reducing transmission.

However, the oral vaccine can very occasionally cause paralysis (about two to three cases per million doses). For this reason, most countries, including the UK, now prefer to use the inactivated vaccine. The oral vaccine is still used in a small number of countries though.

Wastewater monitoring

Children who receive the live vaccine will shed it for a short time in their faeces, which is why we might detect “vaccine-like” polioviruses in wastewater. This normally happens two or three times a year in the UK, where this weakened version of the virus is introduced to the sewage by a child who received the oral vaccine overseas.

This isn’t dangerous in itself, but it’s possible that if these viruses continue to circulate in a population, over time they can mutate, and possibly revert to a version that causes paralysis. These then become classified as vaccine-derived polioviruses. Circulation of vaccine-like and vaccine-derived polioviruses is more likely when fewer children are up to date with their vaccinations.

This is the process which appears to be playing out in London now. From the JCVI’s statement, it’s clear that since the virus was first detected in February, it has evolved and acquired mutations that increase the risk of paralytic disease.

These same genetic analyses show a high diversity of viruses being detected, which suggests the virus is circulating in separate networks of people across affected areas of north London.

The JCVI also stated that occasional positive results are being recorded in areas beyond where the virus was originally detected, including Enfield, Barnet and some areas south of the Thames. So it does appear that the virus is continuing to circulate, and may be circulating more widely than before. If this continues, it would only be a matter of time before we’d start to see cases of paralysis among children who are not vaccinated.

Vaccination is key

Monitoring of wastewater for polioviruses is carried out by many countries primarily to identify when such viruses are circulating in the community, before these viruses start to cause paralysis. The fact the issue was detected in London earlier this year and we are yet to see any cases of paralysis shows that such monitoring is achieving its objectives.

The only effective way to control spread of the virus, and importantly, to prevent the emergence of paralytic disease, is to ensure vaccine coverage is as high as possible. Fortunately we have an ample supply of effective and safe vaccines.

In England the policy has been to give three doses of polio vaccine within a baby’s first 16 weeks, a further booster shortly after three years, and again at age 14. The polio vaccinations are usually given in combination with vaccinations against other conditions.

Part of the logic behind the advice for an additional booster dose is that since 2012 the UK has been offering a whooping cough vaccine to pregnant women to protect their babies in the early weeks after birth. This is the same vaccine used in children at age three which also contains a dose of the inactivated polio vaccine.

There is some evidence that high levels of maternal antibodies to polio may reduce the effectiveness of the first three vaccine doses, meaning children who miss their booster at age three could still be susceptible.

In the affected areas of London, uptake of the polio booster at age three is particularly low, so there is concern that many children in these areas may have inadequate protection. The programme will begin in these areas.

While children who have missed their booster will be most vulnerable, according to the JCVI, offering an additional dose to those who are vaccinated will boost antibody levels and may help to reduce asymptomatic shedding of the virus.

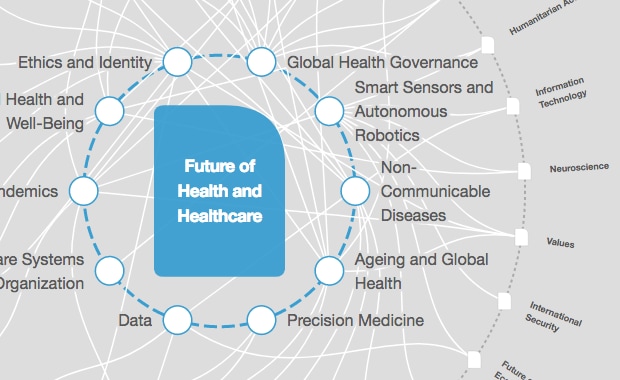

What is the World Economic Forum doing about fighting pandemics?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Health and HealthcareSee all

Johnny Wood

April 17, 2024

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024

Carel du Marchie Sarvaas

April 11, 2024

Nancy Ip

April 10, 2024

Shyam Bishen

April 10, 2024