Deep-sea mining: What you need to know

Deep-sea mining could unlock critical minerals vital to the energy transition, but the process is controversial. Image: Unsplash/matthardy

- Critical minerals, essential for many green technologies, can be found under the sea as well as on land.

- But not enough is yet known about the potential impacts of deep-sea mining to safely adopt it, says a white paper from the World Economic Forum.

- Here’s the latest on regulation, policies, exploration and concerns around deep-sea mining.

The green transition and advances in digital technologies are driving demand for critical minerals, including cobalt, lithium, nickel and other rare earth elements.

As a result, the search for new sources of these vital natural materials has taken us from dry land to beneath the ocean.

Deep-sea mining, which its proponents argue would unlock abundant new reserves of these minerals, remains controversial, however. Minerals on the seabed are under the supervision of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), whose mandate includes the responsibility to establish a governance structure for the use and management of marine resources beyond national jurisdictions.

“The deep seabed needs rules and regulations – it also needs leadership, solidarity and science,” said ISA Secretary-General Leticia Carvalho. Her words followed warnings from President Emmanuel Macron of France, and UN Secretary-General António Guterres at the UN Ocean Conference in June, which also called for caution on deep-sea mining.

The ISA is an independent body through which the parties to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) organize and control mineral resources-related activities.

The organization has been working on a code to govern mining activities under the sea, but its members have yet to reach an agreement. It says commercial activity should not take place until a code is in place.

What do we know about reserves of critical minerals?

With critical minerals such as cobalt, lithium, nickel, zinc, gold and other rare earth metals fundamental to many technologies supporting the green transition – for example, batteries for electric vehicles – securing their supply is an environmental, economic and also geopolitical priority for nations around the world.

As Time points out, the idea of deep-sea mining became particularly attractive in the early 2020s when countries were rushing to secure key metals for electric vehicle (EV) batteries. But EV technology has moved on in recent years, with previously essential cobalt or nickel largely replaced by iron, phosphorus and sodium.

The desire to mine the ocean floor has, however, not shifted. The US, for example, is keen to secure its own reserves of critical minerals, rather than rely on other countries like China.

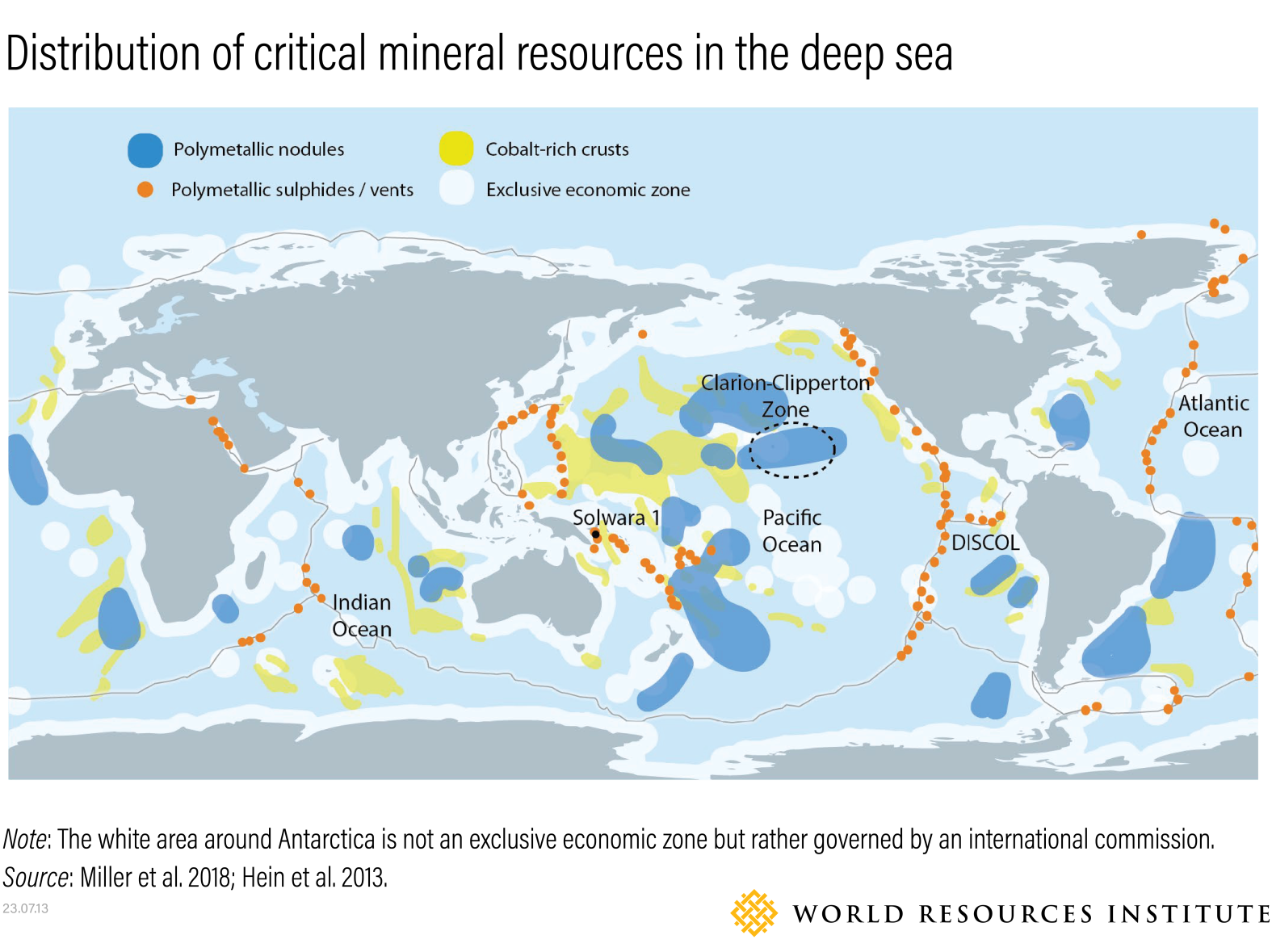

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), the most ‘attractive’ deposits are found in international waters, for example, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean.

Those looking to exploit these reserves are typically searching for minerals and rare elements in three forms: polymetallic nodules; polymetallic sulphides; and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts. Most exploration contracts (see below) are focused on polymetallic nodules.

However, their presence in international waters presents questions over ownership, regulation and governance of any mining activity. Indeed, UNCLOS designates seabed minerals in international waters as the “common heritage of humankind”. It says their extraction must benefit humanity as a whole.

What are the concerns about deep-sea mining?

In addition to the issues of ownership and who would benefit from minerals found in international waters, organizations around the world are concerned about poorly understood impacts on the environment and ocean ecosystems as a result of mining activity. In a 2022 white paper, the World Economic Forum warned of a lack of understanding of potential impacts and a lack of consensus between parties. “Additional knowledge-gathering is needed before deep-sea mineral exploitation can be considered,” the white paper’s authors wrote.

Take the mining of polymetallic nodules. This typically involves a tractor-like machine separating the nodules from the sediment on the seabed, piping them to the surface before returning sediment into the sea.

Potential impacts of activity like this include direct loss of ocean life, longer-term ecosystem damage, impacts on fishing and food security, as well as broader climate risks through the release of sequestered carbon, the WRI says.

Consider, for example, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, where polymetallic nodules are abundant. The WRI reports that over 5,000 new species have recently been discovered here that were previously unknown to science.

As a result of these concerns, close to 1,000 marine scientists and policy experts from more than 70 countries have signed a statement calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, while 38 countries have also made calls for precautionary pauses, moratoriums or outright bans on mining activity.

The private sector is voicing similar concerns. So far, 64 companies and financial institutions have endorsed a moratorium, and in 2021, some major corporations, including Volvo and Google, pledged not to use minerals obtained from deep-sea mining in their supply chains – at least until the impacts were better understood.

So, why the interest in deep-sea mining?

Current extraction and refinement of critical minerals on land is highly concentrated, according to the Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 from the International Energy Agency (IEA). For example, China is the dominant refiner for 19 of the 20 minerals analyzed by the report.

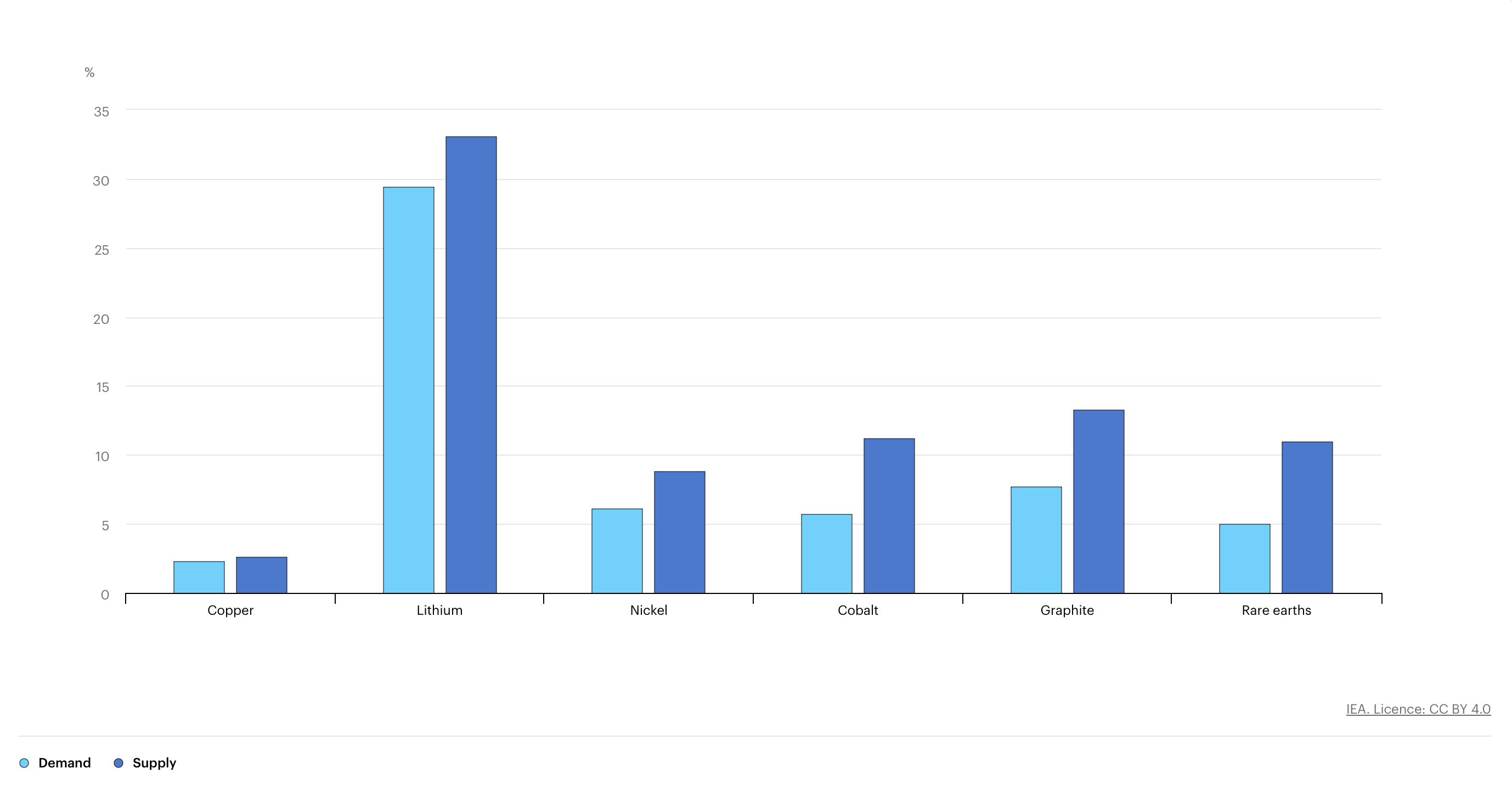

Demand for these minerals is also continuing to rise. Take lithium, which saw a 30% increase in demand last year. And it’s the green transition that, in many cases, is driving demand increases for critical minerals. The IEA says that energy applications are a major factor in rising demand for minerals including lithium, cobalt and graphite, as well as rare earth metals. These applications include electric vehicles (although as mentioned previously, not to the same degree), battery storage and grid networks.

Technology, as well as global collaboration, has the potential to unlock new reserves and diversify supply chains, says the IEA. For example, AI-based exploration could slash costs and boost discovery rates. Recycling of these minerals is also set to improve supply, without the need for new extraction.

Critical mineral supply has emerged as a key element of energy security and a more sustainable future. As a result, the public and private sectors are seeking new reserves.

Private companies involved in the research and development of deep-sea mining argue that new reserves can reduce the environmental strain on terrestrial ecosystems, while nodules can also provide high grades of four key metals with lower levels of waste and toxic by-products.

But other industries and experts disagree. Up to 2,000 times more area would need to be mined at sea to yield the equivalent amount of nickel currently mined on land, says Time. And the argument that deep-sea mining results in less environmental harm is also erroneous, it says, as so much of the deep ocean remains unexplored and therefore potentially at risk of harm.

This is backed up by a recent US study that calculated deep-sea mining would have a negative impact on the environment of up to 13%, as well as a study by UK scientists which showed that 40 years after mining took place in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, “long-term changes to the sediments” had occurred.

What activity is already underway?

The UK study was examining the first successful test of deep-sea mining technology, back in 1970. Commercial viability has only started to emerge in the past few years. Until as recently as 2010, exploration was predominantly the work of national agencies, with private companies only becoming involved then.

ISA has issued exploration contracts with some 22 contractors, which include both national governments and private companies, covering the three forms mentioned above. However, negotiations at ISA’s latest meeting failed to reach agreement on regulations around commercial mining.

US President Donald Trump signed an executive order in April of this year aimed at boosting deep-sea mining in US and international waters. "The United States has a core national security and economic interest in maintaining leadership in deep-sea science and technology and seabed mineral resources," Trump said in the order.

The US is not a party to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and therefore not a member of ISA. Following the executive order, the authority cautioned that undertaking commercial activity outside of a national jurisdiction would be a violation of international law. ISA has since launched an official investigation into the activities of private mining companies seeking regulatory authority unilaterally through the United States, rather than through ISA.

Alternatives to deep-sea mining

If the deep ocean really is humanity’s last frontier, deep-sea mining must be approached with caution.

Many argue it is not even necessary to achieve the green transition. Researchers from the University of British Columbia and the Dona Bertarelli Philanthropy, for instance, advocate for a shift toward circular economy strategies instead. Urban mining as well as better recycling systems are sustainable alternatives, they say, pointing to a recent study on a process that can recover “nearly all the lithium from used electric vehicle batteries for recycling”.

The IEA says that, by 2050, recycled end-of-life copper could supply nearly 40% of total demand, again demonstrating that scaling circular approaches could allow deep-sea mining to be postponed. Technology, as well as global collaboration, has the potential to unlock new reserves and diversify supply chains, it says. For example, AI-based exploration could slash costs and boost discovery rates.

Perhaps the only thing clear right now is that more discussion and research is needed before the world dives into deep-sea mining.

As Dr Diva Amon, marine biologist and Friends of Ocean Action member, said in the Davos 2024 session ‘Live from the Deep Sea’: “What a sustainable deep ocean blue economy does not look like is the unrestrained and rapid rush to mine the deep ocean in the absence of good governance, in the absence of good science, in the absence of stakeholder engagement”.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Ocean

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Ryan Hardin

February 6, 2026