Rethinking climate risk and insurance can help boards boost company value and resilience

Buildings levelled by a December 2022 tornado in Kentucky, US. Climate risk is becoming more systemic. Image: Unsplash/ChandlerCruttenden

Helle Bank Jørgensen

Global Managing Director, Board Development, Board Intelligence; Founder, Competent Boards- Insurance has historically been an effective tool for risk transfer, but it no longer reliably protects corporate assets amid climate-related shocks.

- Continued assumptions about its effectiveness for managing climate risk have created blind spots for many company boards.

- As climate shocks become more systemic, it is increasingly important for companies to explore new ways to manage the resulting intertwined risks.

The economic losses resulting from climate damage could equal 15% of global GDP by 2050 from 2°C of warming and 30% by 2100 from 3°C of warming, according to the Network for Greening the Financial System. These new damage estimates, published in 2024, are three times larger than the organization's earlier assessments.

Insurance has always been used to stabilize markets after crises such as natural disasters. But today’s climate risks are no longer isolated. Droughts, floods, wildfires and biodiversity decline are increasingly interacting, compounding damage and reshaping entire economies. As climate change intensifies natural disasters in this way, it raises risk exposure for physical assets and strains the insurance market.

It is estimated that the insurance burden – the rising share of disaster-related costs shouldered by insurers – has more than doubled over the last 30 years. At the same time, climate change is increasing the difference between total economic losses and those covered by insurance, otherwise known as the insurance gap.

And this gap is widening as climate risk drives new insurance market trends. US insurer State Farm has ceased writing new property policies in high-risk states like California. Employers in those regions already face challenges retaining staff when employees cannot secure or afford insurable housing. In China, the 2021 Henan floods forced Ping An Insurance into payouts exceeding $19 billion.

As climate disasters continue to become more frequent and severe, uninsured damage will likely increase significantly, even without any reduction in insurance cover. The UN estimates that climate-driven disasters could result in a doubling of uninsured losses to up to $560 billion by 2030.

Environmental disruption cascades into finance, labour, supply chains and politics. But even as insurers retreat from high-risk regions, many boards still assume tomorrow will resemble yesterday when it comes to managing climate risk. Boards need to develop new approaches to insurance governance to fully manage the systemic climate risks facing businesses today, and in the future.

Climate risk without borders

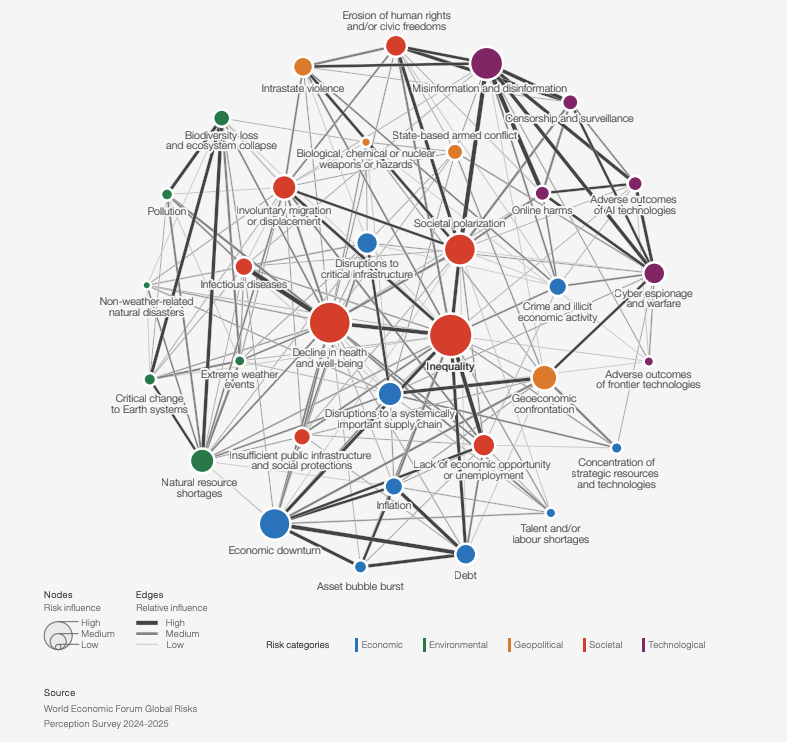

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 maps the interconnected nature of today’s climate-related threats. An extreme weather event no longer just damages property, it can trigger resource shortages, inflation and even social unrest. And when the cost of insuring against such risk rises, the consequences extend far beyond the insurance sector.

Scientists estimate that out of 24,000 people who died in Europe during heat waves from June to August 2025, 16,500 of those deaths were linked to greenhouse gas-driven warming. The growing cost of occupational health and safety amid rising climate risk is expected to show up in higher insurance premiums, increased medical claims and reduced productivity.

Extreme climate also creates mobility bottlenecks. In 2023, extreme heat grounded flights across Southern Europe and the US, stranding many people, including those travelling for business. An insurance policy may cover the cost of a ticket, but it can’t cover the lost productivity or project delays that ripple across value chains as a result of travel disruption.

The world’s resources are also under severe strain due to climate risk. Günther Thallinger, a board member at insurer Allianz, says entire asset classes are "degrading in real time" due to extreme weather. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warns that over one-third of global fish stocks are overfished. Cocoa is threatened by a changing climate in West Africa, and coffee is already experiencing yield declines in Brazil as entire vintages are lost to heat and drought.

Disruption in one region’s value chain could paralyze numerous other industries worldwide. In Taiwan, for example, rising business costs associated with flooding, water stress and heat stress could affect the operations of leading chip manufacturers based in the region that supply vital technology to the rest of the world.

Boards face 5 climate risk blind spots

Boards must rethink their approach to insurance governance. Businesses that fail to adapt risk losing not only their insurance, but also their access to capital and talent.

To stay ahead of the curve, boards need to identify and address five climate risk blind spots:

1. The illusion of predictability

Insurance industry actuarial models are backward-looking. They use datasets that do not assimilate intertwined climate-socio risks and cannot capture unprecedented risks. Climate “tail risks” – rare events with extreme consequences – are poorly understood, leaving boards exposed.

2. A false sense of security

Many directors assume governments or insurers will always provide coverage. But as some insurers cease writing new policies in high-risk regions, this illustrates that insurance availability is never certain.

3. The risk oversight gap

The cascading impact of a lack of insurability on access to finance and the cost of capital must be brought into the company’s risk register. When it isn't, it means a company has not identified this risk or created a plan to help mitigate it.

4. Hidden insurance policy exclusions

Many insurance policies exclude pollution liabilities, non-damage business interruption and supply chain risks. For example, the 2011 floods in Thailand – home to numerous auto parts suppliers – forced global automakers such as Honda and Toyota and Ford to suspend production. This revealed how fragile just-in-time manufacturing can be when local shocks disrupt global value chains.

5. Escalating costs versus coverage

Rising rebuild and compliance costs are already outpacing coverage in some regions. And Pakistan’s 2022 floods, which caused $14.9 billion in damages and required $16.3 billion to rebuild with more resilience, reveal the significant cost of building back better after an extreme weather event.

Insurance as a governance lever

Insurance is no longer a passive backstop. It is a litmus test of a company's governance maturity. Boards must treat it as a lever to incentivize resilience and drive sustainable adaptation investments. This includes mapping interdependencies to understand how housing, transport, supply chains and resources intersect with business continuity.

To do this, board’s must be literate in climate, nature and insurance risks to meet their fiduciary duties. Beyond that, boards should eschew compliance-driven climate scenarios for more adaptive, forward-looking risk management. This would help to embed foresight into their decision-making.

Board directors should be asking key questions about which company assets may become uninsurable or if rising premiums render those assets unviable due to rising climate risk. They should also identify any exclusions that might leave the business vulnerable and consider how cascading risks – not just single shocks – could affect company strategy. Finally, boards must devise strategies to build climate risk resilience, rather than relying on insurance payouts later.

Company boards that continue to treat insurance as a backstop are at risk of discovering it has become a blind spot. Those that embrace it as a governance tool can safeguard resilience, secure capital and unlock long-term value for their companies.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Climate Indicators

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate Action and Waste Reduction See all

Moattar Samim

February 21, 2026