How the green transition will affect labour markets around the world

A new report looks at the impact of the green transition on the economy and workers. Image: REUTERS/Carl Recine/File Photo

- The green transition is reshaping labour markets and could disrupt millions of jobs.

- Making the Green Transition Work for People and the Economy, looks at the impact of the transition on the economy and workers.

- It identifies four distinct groups of countries based on the expected impact of the green transition on jobs.

Addressing the climate crisis and accelerating a green and fair transition is vital to our shared future. Yet there is no single way for countries to achieve this transition – a truth that is crystalized when looking at the impact of the transition on jobs.

As countries move forward with climate mitigation and adaptation policies and the rollout of clean technology, labour markets are being reshaped.

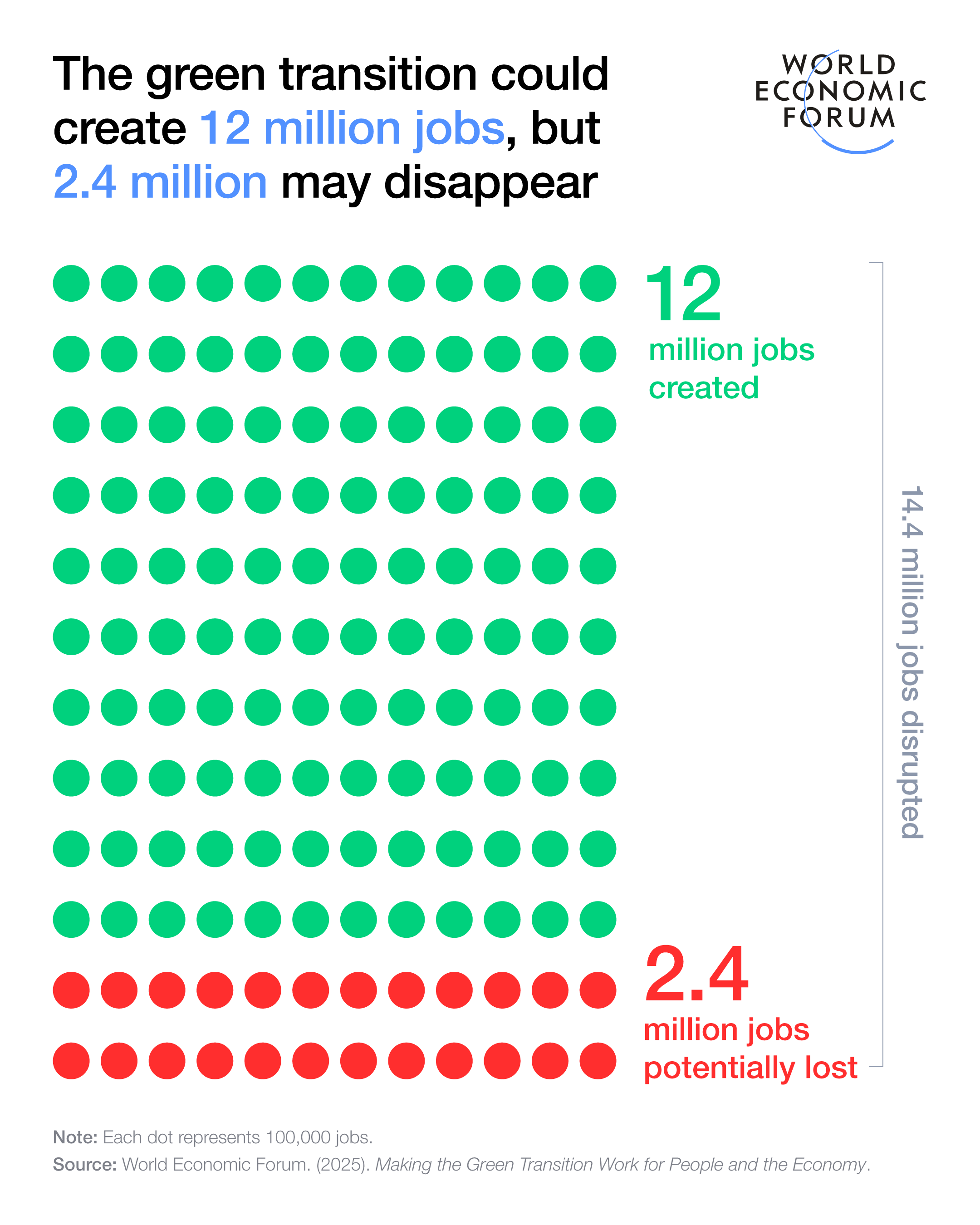

It’s estimated that the green transition will disrupt more than 14 million jobs globally by 2030, with net positive job creation but the potential loss of about 2.4 million roles.

The exact picture will not be the same everywhere. And even countries expecting significant economic benefits can display concern over worker displacement, according to a report from the World Economic Forum and McKinsey & Company.

So how might this play out across the globe? And what can businesses do to maintain competitiveness and support their workers amid this disruption?

Green transition: Economic impact and worker displacement

The report, Making the Green Transition Work for People and the Economy, draws on insights from more than 11,000 executives based in 126 different countries.

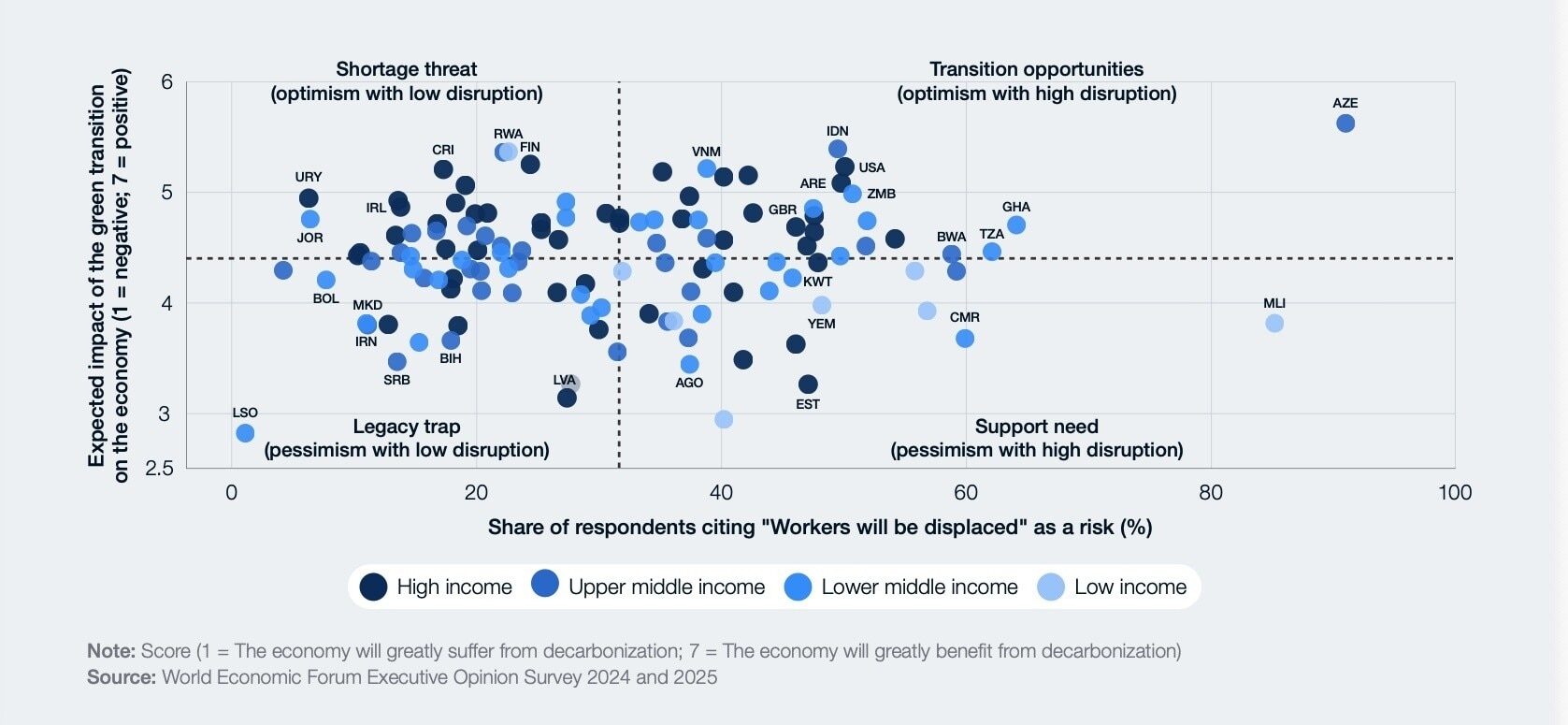

Based on these responses, it examines how the expected impact of the green transition on the economy intersects with the perceived risk of worker displacement.

Four different scenarios of labour-market disruption emerge, as seen in this chart:

Transition opportunities: Optimism with high labour disruption

Clustered in the top-right quadrant of the chart, countries including Indonesia, Brazil, the United Kingdom and South Africa expect the green transition to deliver positive economic outcomes but also anticipate significant disruption to their labour markets.

In such economies, the speed and ease with which workers can transition into new sectors will increase in importance as legacy industries contract and new green activities expand.

Effective mechanisms to support workers – such as helping workers transition to opportunities created by the growing green economy – will be crucial. Without these, displacement risks could slow investment, increase skills gaps and undermine public support for change.

Ensuring disruption is converted into mobility can strengthen competitiveness in the green economy for these nations.

Shortage threat: Optimism constrained by talent

The top-left of the chart contains what might be considered the most favourable scenario: a green transition that delivers positive economic outcomes with limited disruption to existing jobs.

However, in economies in this quadrant – including Mexico, Japan and Malaysia – businesses may still struggle with talent shortages, leading to growth potential being constrained.

In these economies, strengthening education systems, reskilling pathways and labour-force participation will become central to equipping workers with the right skills and sustaining competitiveness.

Support need: Disruption without the economic upside

Countries in the lower-right quadrant face the most acute challenge, with businesses expecting negative economic impacts and high disruption in labour markets.

These economies – which include India, Colombia and Poland – may experience declining industries without sufficient new sources of growth to absorb displaced workers.

Firms could face rising costs and uncertainty while governments will be under pressure to support workers. Social protection and labour support will not be ancillary measures in these places – they will be critical tools for stabilizing the economy amid structural change.

Legacy trap: Stability that masks decline

Finally, in lower-left-quadrant countries, businesses expect negative economic impacts but anticipate limited job disruption.

But while workers will remain employed, it will often be in declining or carbon-intensive sectors with scarce opportunities for reskilling.

This scenario might provide short-term social stability but there are long-term risks. If skills stagnate and productivity declines, workers could face falling wages and fewer prospects without a clear route to reskilling or redeployment.

In these economies – which include Pakistan, Austria and Guatemala – competitiveness may erode gradually rather than through visible shocks.

The key role of social protection

Across all four scenarios, where social protection coverage is higher, concerns over worker displacement decrease. This is true even when disruption is expected to be significant.

Strong social protection, it seems, reduces perceived risk for both workers and firms, enabling more decisive action and smoother adjustment.

This finding reframes the role of labour institutions in the green transition. Social protection is not simply a response to disruption – it shapes how disruption is anticipated, managed and ultimately accepted.

Rethinking competitiveness through a labour lens

As the green transition advances, one out of three businesses globally is concerned about job displacement in at least one major industry in their country.

But the transition will not produce a single labour outcome. Instead, it presents multiple pathways shaped by a nation’s economic structure, labour-market dynamics and institutional capacity.

Human capital will be central to ongoing competitiveness but the challenges vary: some economies will need to prioritize worker mobility while others must focus on talent supply or enhancing social protection.

Understanding potential pathways will be essential for designing economically and socially durable transition strategies.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Contents

Green transition: Economic impact and worker displacementTransition opportunities: Optimism with high labour disruptionShortage threat: Optimism constrained by talentSupport need: Disruption without the economic upsideLegacy trap: Stability that masks declineThe key role of social protectionRethinking competitiveness through a labour lensForum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Pooja Chhabria

February 27, 2026