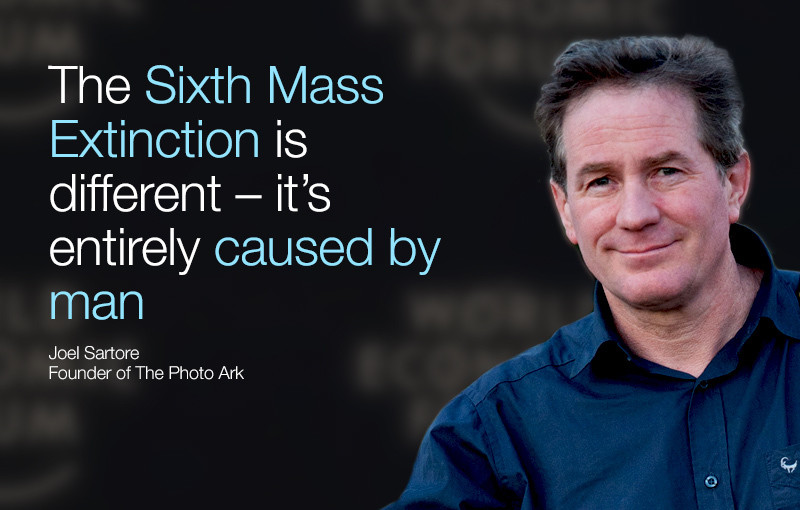

The Sixth Mass Extinction is upon us. And it's our fault

It’s folly to think that we can lose half of all other species, but that we’ll be just fine. Image: REUTERS/Michael Fiala

Simply put, the Sixth Mass Extinction is a massive die-off of plants and animals all across the planet. There have been five others throughout time, but this one is different; it’s entirely caused by man.

Habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, poaching and over-consumption of resources are all coming together to possibly eliminate half of all species by the turn of the century.

Why should we care?

Because it’s folly to think that we can lose half of everything else, but that we’ll be just fine.

Though we may forget it in our workaday world of interest rates, air conditioning and sporting events, we really do need nature to survive.

For example, we must have insects like bees and even flies to pollinate our crops.

We must have abundant rainforests to regulate rainfall, keeping it coming in just the right amounts to the regions of the world with good soil and people who know how to grow the crops that feed a hungry world.

We must have healthy oceans, full of corals, phytoplankton, zooplankton and fish. This too stabilizes our climate and also feeds the world.

Source: Joel Sartore/ National Geographic’s Photo Ark

And we must have ice in the polar regions, even in the summer. Ice reflects most of the UV hitting it, while open ocean absorbs most solar radiation. When we go ice free at the poles in the summer, the climate of the Earth could heat up so quickly it’ll make our heads spin.

The list goes on and on.

So what to do? It all starts with you.

Whether you’re an individual or the leader of a global conglomerate, know that each financial decision you make most likely either helps or harms the planet. Clear cutting of old growth trees, sprawling development, burning of dirty fossil fuels, inefficiency in manufacturing, and toxic waste all contribute to the planet’s woes.

But it’s not too late to turn things around.

Using clean and sustainable energy sources is important, to be sure, but also the protection of large tracts of wilderness is critical if we’re to keep our planet in balance.

Source: Joel Sartore/ National Geographic’s Photo Ark

To date, the majority of people haven’t cared too much about this sort of thing. Yet bringing about a change in how we all view nature is key if we’re to reshape everything from consumer spending habits to overpopulation.

But how do we get there?

It won’t do much good to scare the public. They’ll just tune out.

Perhaps the best way to get people to care is to make environmental issues interesting, and even fun, in order to compete with all the other distractions in their daily lives.

That’s the whole premise behind the Photo Ark, my 25-year project to document animals around the world as studio portraits. Each new species can get the public into the tent of conservation, and get them to care, while there’s still time to save species.

I work at zoos, aquariums and private breeders, today’s keepers of the kingdom. They do a tremendous job, from captive breeding of critically-endangered species, to habitat preservation to connecting the public to biodiversity. The ability to see, smell, hear and touch (at least some of the smaller animals) can change people’s understanding of nature in a very powerful and lasting way.

Source: Joel Sartore/ National Geographic’s Photo Ark

Similarly, it is hoped that the Photo Ark’s studio-style portraits can get people to care about all creatures, great and small. Clean backgrounds eliminate size comparisons and level the playing field. A tortoise counts as much as a rhino. We can also look them directly in the eye and quickly see that these creatures contain beauty, grace, and intelligence. Perhaps some even hold the key to our very salvation.

The plain truth is that when we save species, we’re actually saving ourselves. Individual plants can provide us with chemical agents that we can use for medicines. And animals teach us new things all the time about things as varied as communication (dolphins), hibernation (Arctic ground squirrels) and pollution (freshwater mussels).

Beyond all the self-serving reasons though, each and every species is a work of art, created over thousands or even millions of years, and is worth saving just because each is so unique and priceless. They enrich our world as nothing else can.

Source: Joel Sartore/ National Geographic’s Photo Ark

And one more thing for those of you who still don’t know what to do about all this.

Know that every time you break out your purse or your wallet, you’re saying to a retailer, “I approve of what this was made from, the distance it was shipped to me, and I want you do to it again and again.” The power of the dollar is real, and it moves mountains if enough people pay attention. What kind of wood is that new dining room set made of? Do you eat less meat, and locally-grown fruits and veggies in season? Do you wash laundry using a cold water detergent? What’s the packaging on the products you buy? Have you bought a smaller car and do you drive it less?

No one person can save the world, but each of us certainly can have a real and meaningful impact. Many of the species that are featured in The Photo Ark can indeed be saved, but it will take people with passion, money or both to step up and get involved. A little attention is all some need, while other species range globally and will be harder to protect. Every bit of effort helps though, and awareness of the problem is the first step towards a solution. People can’t save what they don’t know exists.

The bottom line for me is this: at the end of my days, I’d like to be able to look in the mirror and smile thinking that I made a real difference. Long after I am dead, these pictures are going to go to work every day to save species. There’s no more important mission for me.

Now, how about you?

Author: Joel Sartore, Contributing Photographer, National Geographic Magazine, USA. He is the founder of The Photo Ark, a multi-year documentary project to save species and habitat. He is participating in the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Forum in FocusSee all

Gayle Markovitz

October 29, 2025