The war on drugs has failed. Now what?

The drug war has been a disaster, but it's not too late to turn things around. Image: REUTERS/Juan Medina

Latin America is the world's most violent region. It is home to one tenth of the world's population - and more than one third of its homicides. Brazil, a regional powerhouse, tops the global charts with close to 60,000 murders a year. Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico and Venezuela are some of the most dangerous countries on the planet. It is estimated that at least half of the violent deaths occurring there are drug-related.

The war on drugs is contributing to sky-high rates of lethal violence not just in Latin America, but in parts of the US, Europe, Africa and Asia. After governments started criminalizing drug producers, petty dealers and consumers, human rights violations spiraled upward. Many countries experienced dramatic expansions in their prison populations. Meanwhile, the profits of organized crime groups continued to soar to $320 billion per year, and their ability to buy-off politicians, police and judges grew.

Virtually everyone now agrees that the war on drugs has been a spectacular failure by almost every measure. Richard Branson, a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, has said that if the drug war were a business, he'd have closed it down 40 years ago. Even the UN Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC) now publicly admits that the term is "unhelpful" and is exploring a more balanced approach that includes both law enforcement and harm reduction strategies, putting health and safety first and decriminalizing drug users.

The bad news is that there are still some governments that believe drug prohibition is possible. They still insist on continuing a flawed war launched by former President Nixon in the early 1970s. They cling to outdated ideas. They rely more on ideology than evidence. Some of them are simply ignorant to the harms generated by irrational drug policy.

Here are three ways that the war on drugs has fallen short.

First, the war on drugs has utterly failed to reduce the supply of illicit drugs on international markets. Fumigation, eradication, and crop substitution programmes have had almost no effect on aggregate production of cocaine, heroin, or marijuana. In spite of massive investments by the U.S. and others in Bolivia, Colombia and Peru - the countries responsible for almost 100% of cocaine production - coca cultivation is in fact stable over the past decade. If anything, they've only succeeded in making life more miserable for poor communities and farmers.

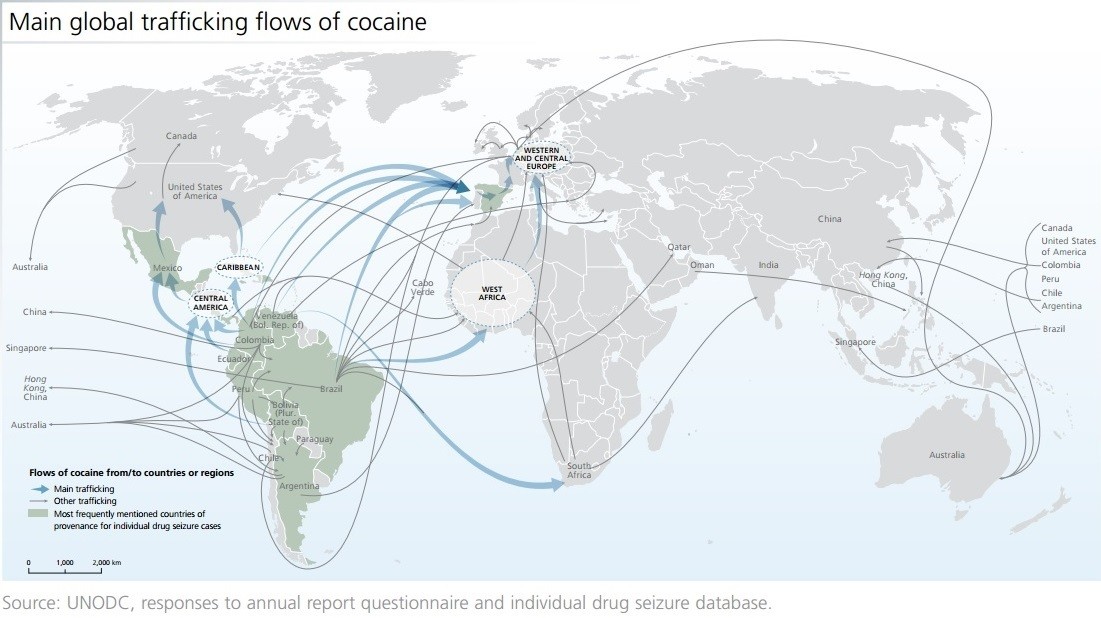

Second, counter-narcotics policies have also been unable to contain transit of drugs from Latin America to North American and European markets. About 90% of the cocaine consumed in the United States comes from Colombia, while 90% of the cocaine used by Europeans is from Peru. Virtually all of this product is transferred through countries in Central America, the Caribbean and South America. Not only has it persisted unabated, but its transfer has also greatly expanded corruption of politicians, customs officials, police and has spread violence and increased consumption throughout these regions.

Third, the drug war has been a complete disaster when it comes to demand reduction. In 2013, there were around 246 million people between 15-64 years of old who are believed to have used an illegal drug in the previous year. This represents an increase, not a decrease, on previous years. What is more, consumption has increased dramatically in Latin America. Abstinence only programmes have made no impact on levels of use. Meanwhile, life-saving drugs are still heavily restricted.

The good news is that there are several ways to turn things around. Since 2011, a Global Commission on Drug Policy has helped governments, businesses and civil societies identify a range of alternatives to drug prohibition. Chaired by former Brazilian President, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the Commission has issued influential reports, started up a global campaign for reform, and reached out to sitting leaders around the world. In 2016, the Commission will be appealing to a General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) to develop a more effective and humane approach to global drug policy.

So what is the Global Commission pitching? At the most basic level, the 23 commissioners believe that the status quo is unacceptable and unsustainable. Global drug prohibition not only failed to achieve its original stated objectives of eradicating drug production and consumption, it also generated alarming social and health problems. The commissioners are also hopeful given that drug policies are changing around the world. Many governments are already embracing innovative and effective ways of reducing the health and social harms caused by drugs.

The Global Commission on Drug Policy is making a few very basic recommendations to UNGASS. All of them are intended to do what the original drug conventions mandated - put people’s health, community safety and human rights first. The key suggestions are straight-forward and based on what works:

- Invest in evidence-based prevention, treatment and harm reduction measures as cornerstones of drug policy

- Ensure equitable access to essential medicines that relieve unnecessary pain and suffering

- End the criminalization and incarceration for drug use and possession for personal use

- Abolish capital punishment for drug-related offences; redirect law enforcement away from non-violent participants in the drug trade towards fighting violence, corruption and organized crime

- Rebalance repressive policies away from eradicating crops and arresting farmers to promoting community development

- Empower the World Health Organization to review the scheduling system of drugs on the basis of scientific evidence

These priorities constitute a minimum agenda for UNGASS. The move toward regulating drug markets is inevitable. It is only by putting governments back in control that organized crime groups can be disempowered and associated corruption and violence reduced.

Author: Ilona Szabó de Carvalho, executive-director of the Igarapé Institute, Brazil and executive coordinator of the Global Commission on Drug Policy Secretariat. You can watch her TED talk here. She is participating in the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Latin America

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Forum in FocusSee all

Gayle Markovitz

October 29, 2025