Paris or Manhattan: Which type of city is best for reducing emissions?

The costs of not addressing the climate crisis were made abundantly clear in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. Image: Flickr/Frederic

- A new report has looked at greenhouse gas emissions over the whole lifecycle of a building, including building and servicing.

- It suggests high-density, low-rise cities such as Paris may be best for reducing emissions.

- Net-zero goals have largely targeted operational energy use, not emissions associated with building.

As humanity grapples with the climate crisis, consensus has been growing that increasing urban density is a greener way to live.

But according to new research published in the journal Urban Sustainability, the most effective way to build a sustainable city is not high-rise, but high-density low-rise housing.

"Our results show that density is indeed needed for a growing urban population, but height isn’t,” said the lead author and Edinburgh Napier University professor Francesco Pomponi.

“So it seems the world needs more Parises and fewer Manhattans – as much as I love New York – in the next decades.”

Low rise, high density

The researchers looked at greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over the whole lifecycle of a building, including building and servicing the structures.

They concluded that high-rise, high-density buildings increase GHG emissions by 154% compared to low-rise, high-density buildings; while low-density housing required 142% more land.

The researchers say urban environment design has principally focused on operational energy use – which is getting more and more efficient – and has not properly considered “embodied” energy. That is “energy and emissions that are used or generated during the extraction and production of raw materials, the manufacture of the building components, the construction and deconstruction of the building, and the transportation between each phase”.

Building better

With an extra 2.5 billion people expected to be residing in cities by 2050, the debate about the most efficient way to house people is critical.

Urban areas account for 78% of the world’s energy use and city leaders across the world say they want to take responsibility and do more to reduce carbon emissions.

Transport and buildings are among the biggest contributors – the construction industry is responsible for about 40% of all carbon emissions.

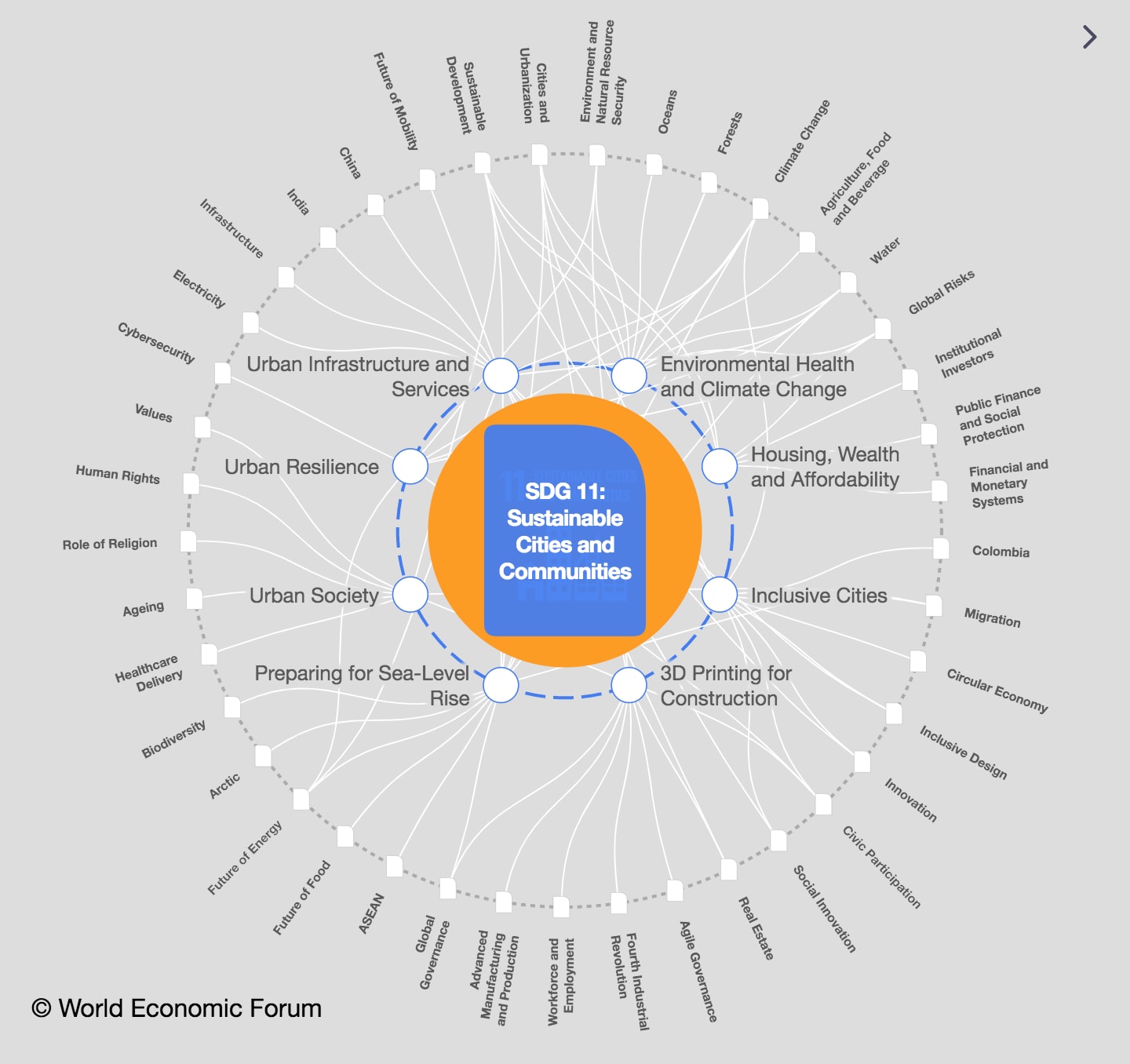

What is the World Economic Forum doing to promote sustainable urban development?

So what are the solutions?

Los Angeles has, as part of California’s Green New Deal policy, adopted guidelines to reduce GHGs from building materials. It is “the first local government to regulate the global warming potential of steel, flat glass and mineral wool procured by the city”, according to the C40 group of almost 100 cities committed to tackling climate change.

In Norway, the city of Oslo has a zero-emissions target for municipal building sites by 2025, extending to all construction sites by 2030. This means that construction equipment will be required to move from fossil fuel to electric-powered – 98% of Norway’s electricity comes from renewable sources.

The C40 group says it’s not enough for buildings to be net-zero in terms of operational energy use, and has launched a declaration aimed at reducing embodied emissions by at least 50% for new buildings, major retrofits and infrastructure projects by 2030.

Rapid action

The costs of not addressing the climate crisis were made abundantly clear in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. It stated that “immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions” in GHG emissions would be required to limit global warming.

Human activity is responsible for the temperature rise, according to the panel, and a failure to act would result in warming of 1.5 or 2°C within 20 years. The effect of that warming is more intense rainfall and flooding, severe coastal flooding and erosion, and more frequent heatwaves.

And the greatest costs of climate change – in both lives and money – are likely to be borne by city dwellers. Around the world, 70% of cities are dealing with climate change, and 90% of urban areas are coastal, and therefore vulnerable to sea level rises.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Forum in FocusSee all

Gayle Markovitz

October 29, 2025