Can we build a people and nature-positive future with systematic land use?

It's vital to consider biodiversity when apportioning land use. Image: Anne Nygård on Unsplash

Scott Vaughan

International Chief Adviser, China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and DevelopmentListen to the article

- Human exploitation of natural resources is often underestimated or overlooked.

- To combat this, we need a systematic land use approach where we reassess and reallocate land into productive, regulative, supporting and cultural functions to synergise economic, social and environmental goals.

- With proper science, technology, financial tools, management and the will to overhaul unsustainable development models, we can improve the health of our planet.

“If Earth’s history is compared to a calendar year, modern human life has existed for 37 minutes, and we have used one-third of Earth’s natural resources in the last 0.2 seconds.”

Human exploitation of natural resources is often underestimated or overlooked. The global environmental footprint, which measures human demand on the Earth’s ecosystems, recently tallied in at a whopping 1.8 Earths. Evidently, our resource consumption has outrun the planet’s regenerative capabilities.

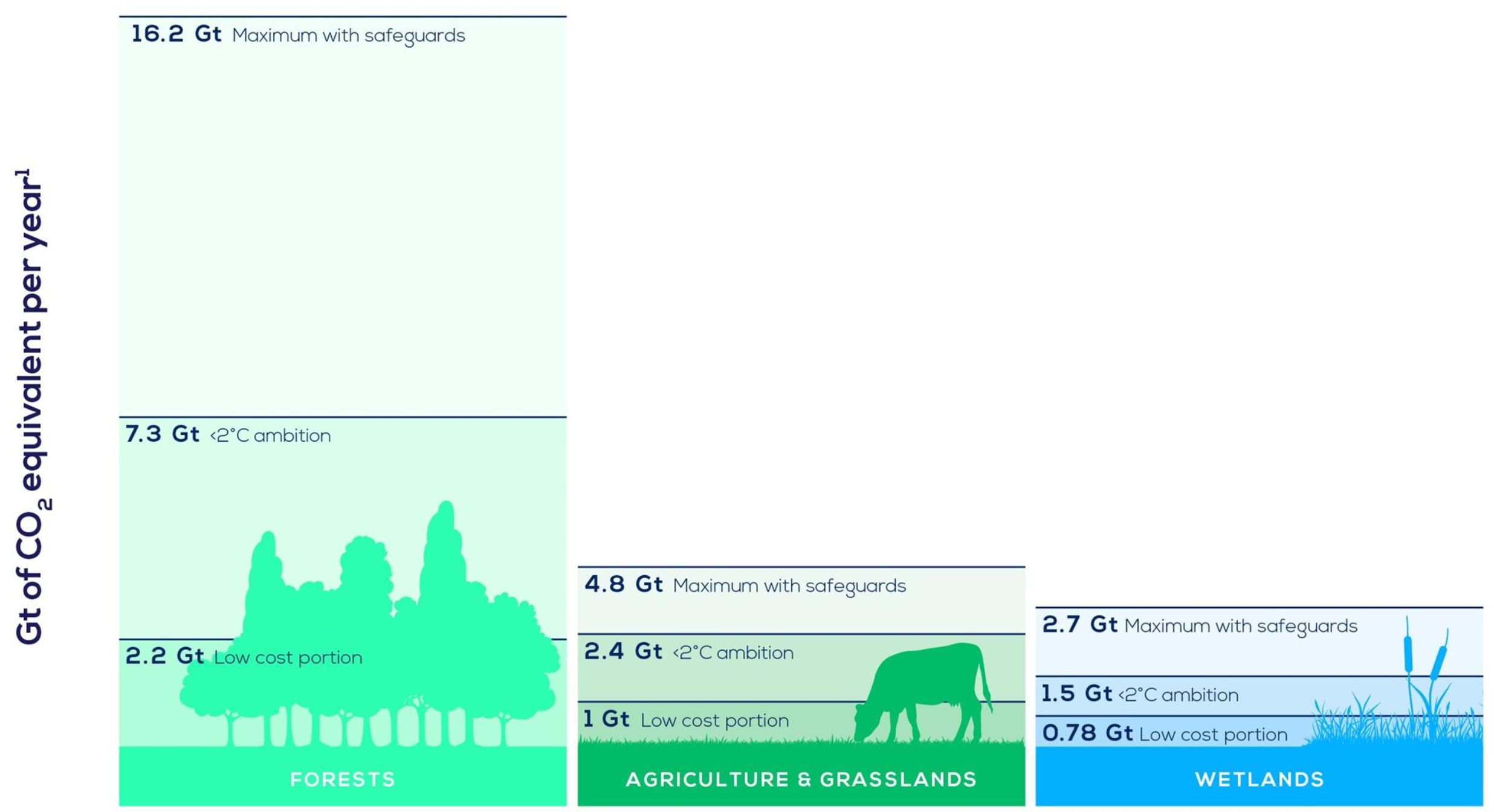

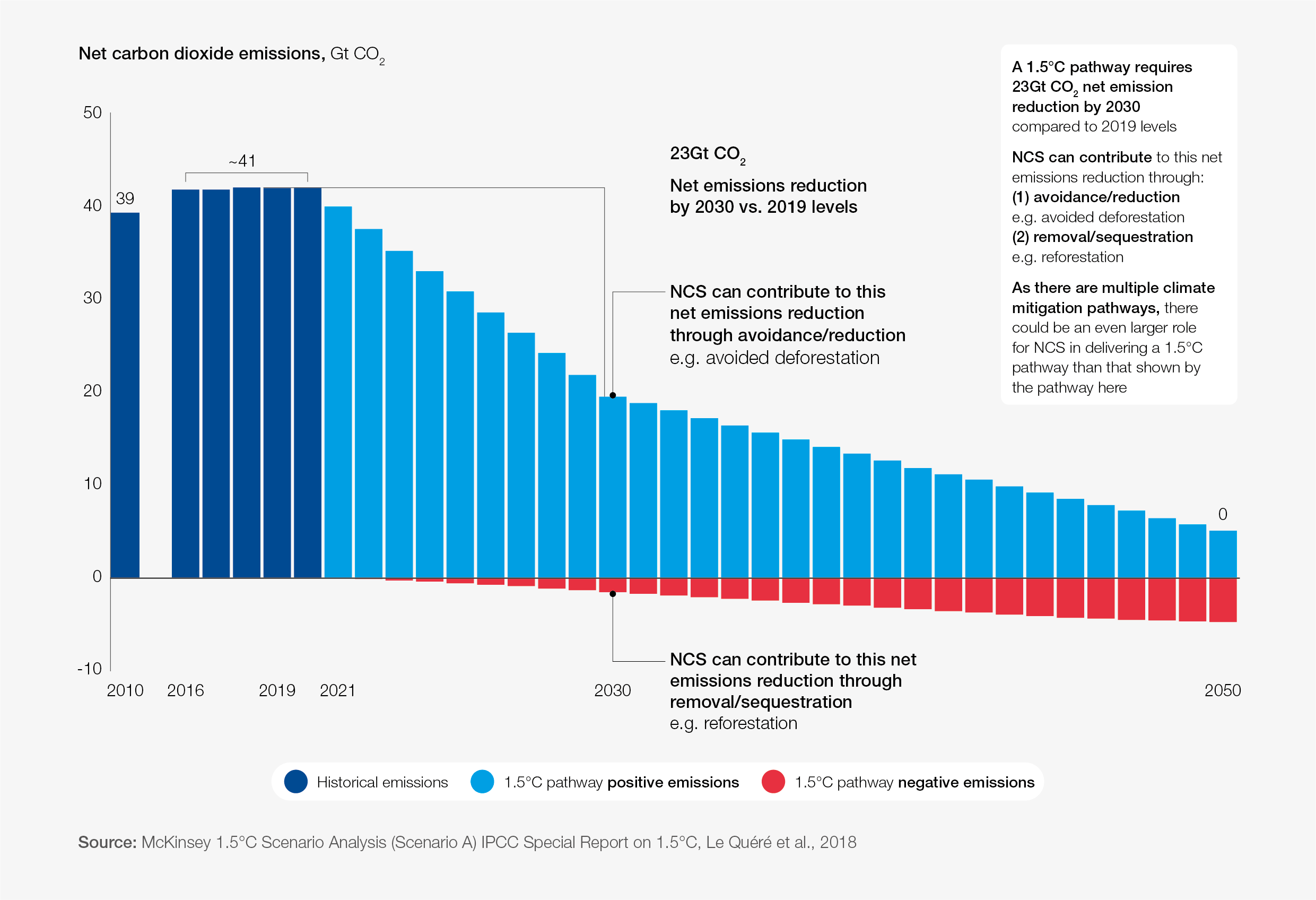

What is the World Economic Forum doing on natural climate solutions?

Rethinking how we use land

With only one earth underfoot, if we are to extend – even by a little – the Anthropocene Epoch, we must uproot, rethink, redesign and reorganize the way we use the Earth’s surface. This is what we call a systematic land use approach: reassessing and reallocating land into productive, regulative, supporting and cultural functions to synergise economic, social and environmental goals and to drive a paradigm shift in human society’s development trajectory.

Land is the most fundamental and essential bedrock upon which all human livelihoods and production are made possible. Through agriculture, forestry, mining and other uses, land offers the food, water, and energy necessary for human subsistence, alongside a plethora of economic rewards. Land is the basis for natural capital and ecosystem services.

While land is a bountiful asset, it is also a finite resource. Since the onset of the first Industrial Revolution, exponential technological and economic growth has resulted in skyrocketing rates of land and freshwater use, along with heightened consumption of food, feed, fibre, timber and energy, leading to wide-scale land degradation. Around 75% of the terrestrial environment and 66% of the marine environment has been severely altered by humans. But it doesn’t end there. Land degradation then contributes to increasing net greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), loss of natural ecosystems, declining biodiversity and the increased vulnerability of marginalised groups. It is estimated to impact the well-being of at least 3.2 billion people.

Land use choices are inextricably tied to the state of nature and climate. Land can be a source or a sink of GHGs, it can either sustain or deplete biodiversity. Land is at once the problem and the solution, depending on how we choose to manage it.

Understanding land locally and globally

Though land use and cover change (LUCC) often occur at a local level, its aggregated impacts can cascade into critical blows on Earth system processes. The land use objectives of different sectors and stakeholders are not always compatible and are often conflicting. Prioritising a certain geographical region or a certain land function often triggers trade-offs over space, time and among stakeholders (see Figure 1 below).

The rapid expansion of Brazilian soy production, for example, has entailed economic growth and improved food security for farmers and the country. The conversion of forests to croplands, however, has led to biodiversity loss, increased carbon emissions and caused damage to the regulating and supporting ecosystem services of forests in general, which will result in negative externalities on local, regional and global levels.

The role of trade is an important factor in sustainable land management. On one hand, trade provides an incentive and prompts local stakeholders and large-scale investors to utilise land in accordance with its natural resource endowments and comparative advantages. This specialisation linked to trade can magnify ecological disruption through scale effects.

On the other hand, land is the basis for many public goods, such as water quality, biodiversity and a stable climate, all of which can be traced back to land use. As such, on a global scale, securing public goods will be the priority, while at a local scale, local stakeholders will seek to increase production and improve their livelihoods—these two objectives might clash. Therefore, land-use planning not only has to balance land-use functions but also must consider and mediate the benefits of stakeholders at every step.

Currently, short-term needs and economic gains are the primary motives behind land use decisions, overlooking the long-term and widespread risks of unsustainable land use change.

Adopting a systematic land use approach

To achieve a more harmonious and sustainable development, a systematic land use approach is needed. Enhanced coordination that takes into account different geographical scales and competing land functions can minimise or even eliminate trade-offs, enabling synergy between conservation and development goals.

For instance, agrivoltaics is an increasingly popular approach that uses the same land area for solar photovoltaic and agriculture, by elevating solar panels and growing crops underneath them. The Aurora Solar Project in Minnesota is an attempt at incorporating pollinator-friendly plantings in agrivoltaic projects. By planting pollinator-friendly vegetation in and around solar panels, it provides habitats for wild insect pollinators, improves water quality, reduces soil erosion and increases crop yields thanks to more pollination services.

Similarly, solar farms in Qinghai have planted grass using the water flowing down from cleaning solar panels. The Hainan prefecture in Qinghai now has more than 22,000 cattle and sheep grazing on these solar farm pastures. Owing to agrivoltaic projects, the prefecture has also seen a 50% decrease in wind speed, a 30% decrease in soil moisture loss and an 80% increase in vegetation cover.

Another example is the Central American Dry Corridor, which has been identified as highly vulnerable to climate change due to heat waves and unpredictable rainfall. Efforts are now underway to protect from this. Farmers are growing trees on once-deforested land with redesigned agroforestry systems that combine tree cover with crops, such as coffee, cocoa and cardamom. This approach helps trap moisture in the soil and shield crops from the sun, effectively maintaining biodiversity in tropical forests while improving livelihoods. The 2030 target is to restore 100,000 ha and create 5,000 permanent jobs.

In collaboration with the China Council for International Cooperation and Development, the Eco-Civilization Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, GIZ and the Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology, the World Economic Forum has launched a pilot project, a scoping study on Integrated Land Use in China. The study aims to identify critical issues in creating synergy between biodiversity targets, dual-carbon goals and water and food security through land use optimisation.

90% of land could become degraded by 2050, stripping businesses of the very resources they rely on and backtracking advances in socio-economic development. Compounded by the effects of land degradation on climate change and biodiversity, sustainable land use is essential to safeguard and future-proof businesses. According to the World Economic Forum’s insight report Seizing Business Opportunities in China’s Transition Towards a Nature-positive Economy, nature-positive transitions in food and land-use-related sectors could create $502 billion of annual business value and 29 million jobs by 2030 in China. Moving forward, it is imperative for businesses to reassess the impacts of their operations on land in relation to biodiversity, climate, freshwater and the ocean and adopt science-based targets for nature.

It was encouraging to see at the Redesigning Land Use for People and Planet session at the Annual Meeting of the New Champions, in June 2023, that governments, academia, business and civil society seem to be taking steps to improve the health and sustainability of the Earth. Wang Guanghua, Minister at the Ministry of Natural Resources, People’s Republic of China, said: "The Ministry of Natural Resources is actively practising President Xi's thought on ecological civilization, implementing the fundamental national policy of 'conserving resources and protecting the environment,' following the work strictly adhering to the bottom line of resource security, optimizing the spatial pattern of the country, promoting green and low-carbon development and safeguarding the rights and interests of resource assets. In addition, we will adhere to the policy of sustainable development, prioritising conservation, protection and natural restoration and continuously optimising land use to promote sustainable development."

Zhang Yongsheng, Director-General and Research Fellow at the Research Institute for Eco-civilization, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, added: “To tackle the issues of land use and biodiversity loss, climate change, food security, water security and environmental pollution, it is necessary to think outside the traditional industrialisation paradigm and transform the conflicting relationship between land use, food and ecology under the traditional industrialisation model into a mutually reinforcing relationship under an ecological civilization. Only in this way, will it lead to a nature-positive economy in China.”

David Fang Jun-tao, Senior Vice President, Corporate Affairs and Sustainability, Zone Greater China, Nestlé, said: “In China, we’ve already commenced many pilot projects in partnership with companies such as Syngenta and Bayer. We were working with Syngenta on a corn and wheat project in Shandong province and earlier this year we launched regenerative agriculture cooperation with Bayer on rice in Heilongjiang. Soil is an ideal vessel for carbon sequestration and reducing emissions, if we can restore the carbon sequestering capacity of soil and other ecological resources, there is tremendous potential to realise our ecological goals. We hope to see more support for regenerative agriculture in the future.”

The photovoltaic industry is also a consumer of land, explained Dany Qian, Global Vice-President, JinkoSolar Holding Co. Ltd. She said: “We’ve been thinking about how to co-exist and prosper alongside land, rather than allowing the industry to develop at the expense of land. Jinko Solar has been promoting integrated land use on our solar farms in the mid-eastern region of China, for example, elevating solar panels by 1.5m to 2m and planting shade-tolerant plants underneath them. When placed above bodies of water, shading provided by solar panels can also reduce water surface temperature, which is beneficial to the growth of aquatic plants, fish and shrimp.”

Alex Sun, Chief Sustainability Officer at Envision Group, said: “We’ve mentioned Inner Mongolia a lot today, we can attribute its popularity to the fact that it used to be the coal capital of China, but also because of its rich solar and wind capacity. That’s why Envision Group has built many solar and wind power plants in degraded and desert areas surrounding Ordos, Inner Mongolia, which then supplies 100% renewable energy to our net-zero industrial park there. After replacing fuel with EV batteries in all heavy-duty trucks in the Ordos area, according to our calculations, we can reduce 30 million tons of carbon emissions for the local community, which is a very significant figure.”

Representing civil society, Zhou Zhou, President of the Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology; (SEE) Champions for Nature, explained: “SEE Foundation both represents a Chinese philanthropic organization and serves to connect Chinese entrepreneurs. 120 of our member companies have made commitments to conserve nature through the Business for Nature coalition and we also encourage Chinese companies to utilise international tools, such as Science Based Targets for Nature (SBTN) to assess the impact of their operations on land, freshwater, biodiversity and more and to set scientific goals to promote nature-positive corporate transitions."

Charles Owubah, Chief Executive Officer, Action Against Hunger USA, concluded: “Solar energy is available. However, as I travel all over the world, nobody is using solar energy in the rural communities. They live on the land. They're burning the trees and everything. Unless and until there's a plan to make sure that what is available in modern cities is also available to the people living on the land today, we will come back 10 years later.”

A perilous and promising moment

The sheer magnitude of human impact on Earth has invited the denomination of a new geological age — the Anthropocene Epoch. The pen of history moved from nature, where she had been for 4.5 billion years, to mankind. While it is a grim reminder of the damage done, it is also a testament to human potential. With proper science, technology, financial tools, management and, above all, the will to overhaul unsustainable development models, we can turn it around.

Our generation is at an inflexion point in the evolution of the planet and human life. By 2030, we will have largely decided the next hundred years or more — whether it will be a century of snowballing destruction or whether we stand a chance at stabilising and restoring the environment. Now is a perilous moment, but also a promising one for us to decide humanity's destiny. Here and now, we are staring peril and promise in the eye.

Susan Hu, Nature Action Agenda China Specialist; Siyu Wang, Nature Positive China Communication Specialist and Zi Qing Chan, Nature Positive intern also contributed to this article.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Climate and Nature

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Forum in FocusSee all

Gayle Markovitz

October 29, 2025